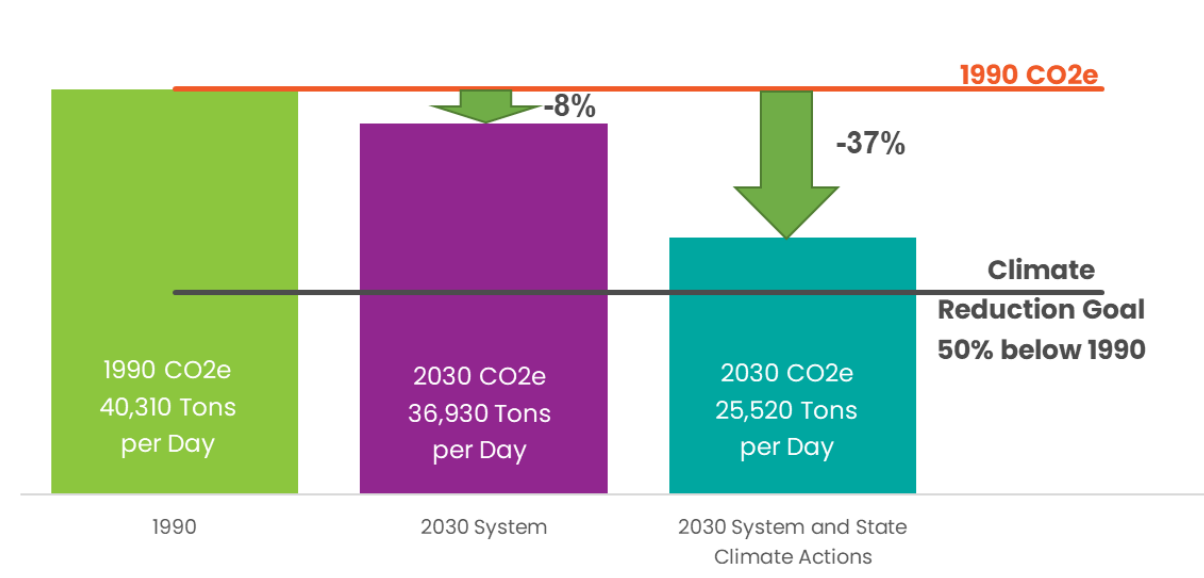

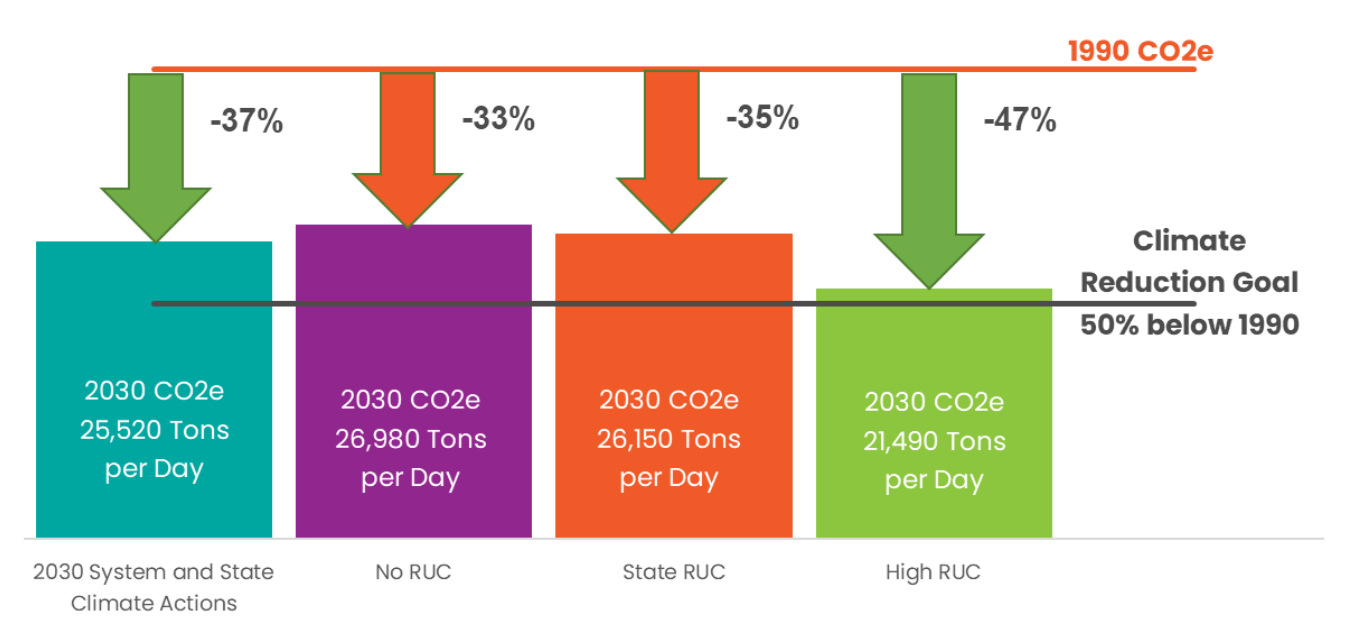

Just a few months after adopting a long range transportation plan intended to guide investments through 2050, staff at the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC) have revealed that the plan is not ambitious enough to guide the four-county central Puget Sound toward its adopted 2030 climate target. At a meeting of the body’s executive board last week, staff revealed that new analysis shows a projected 13% gap between anticipated emissions and the goal of reaching a 50% reduction of the region’s 1990 greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, even with the help of numerous newly adopted statewide climate policies.

The original version of the plan, as proposed nearly a year ago, focused almost entirely on a 2050 climate target, but amendments from elected officials serving on PSRC’s policy boards forced the agency to conduct additional analysis after the adoption of the plan in May to see how on track King, Snohomish, Kitsap and Pierce counties are to hit the more immediate goal at the end of this decade. Thanks to that pushing, additional work to get the plan more focused on immediate emissions reduction is now underway.

But after determining that 13% gap, equivalent to more than the City of Seattle’s entire pre-pandemic transportation sector emissions, models examining ways to fill that gap came up short in a number of key areas. Policy levers modeled by PSRC had minimal impact on emissions, raising more questions about the models used than anything.

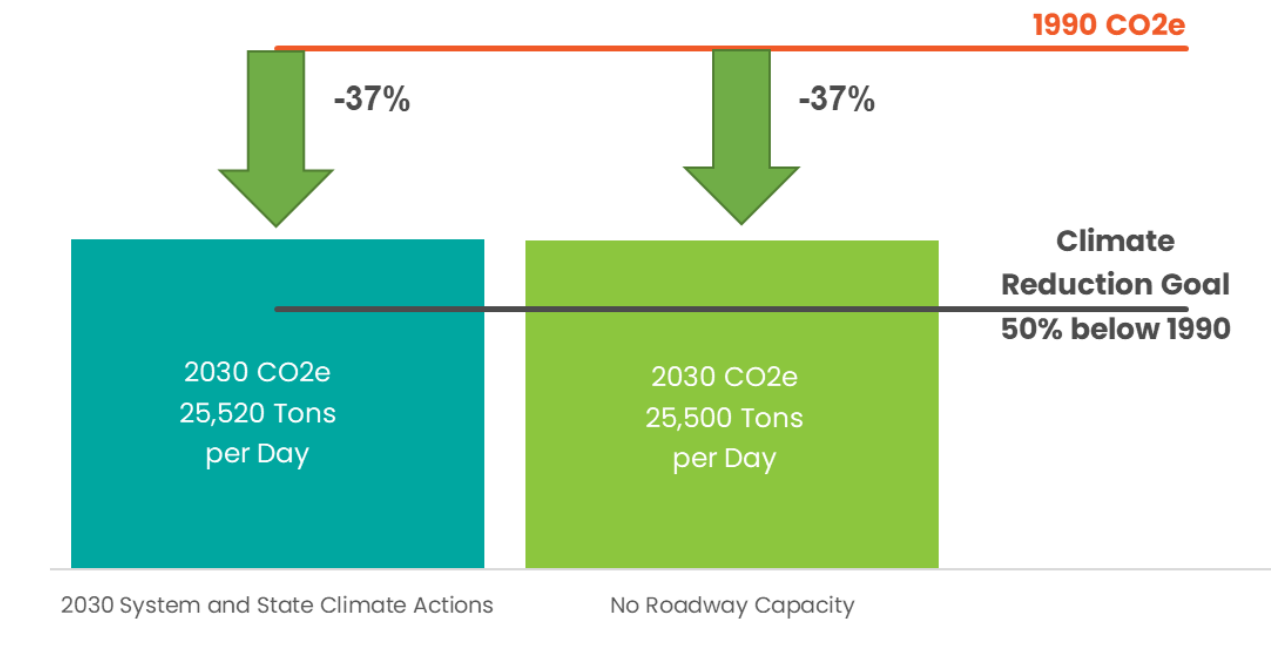

Roadway Expansion Projects

Looking at the hundreds of millions of dollars in roadway expansion projects currently included in the plan’s project list, PSRC concluded that their removal would not improve overall emissions. While overall vehicle miles traveled (VMT) would not increase as much if the region stopped expanding those roadways, their models say, “emissions are not reduced due to the increased delay and amount of time vehicles are in congestion.”

This is bizarre, because the universe of projects included in the plan, expected to increase the number of lane miles regionally by 2% by 2030 and 4% by 2050, still won’t be enough to outpace traffic congestion. By 2050, the annual hours of “delay” recorded regionally due congestion is expected to increase by more than 50%. The plan already acknowledges we can not build our way out of traffic congestion, and yet it just so happens that not building the widening projects in the regional transportation plan would increase emissions.

PSRC’s Director of Data, Craig Helmann, presenting to the executive board, actually noted that the agency compared its traffic model to the induced demand calculator developed by the Rocky Mountain Institute, unveiled last year. The SHIFT calculator creates estimates of the amount of traffic that will be added onto roadways when urban highways are widened. “The Calculator provides transparency and accountability for transportation projects that often do not deliver on promised benefits and instead make traffic and pollution worse,” the Institute noted when the tool was created.

While Helmann described the two models as showing extremely similar results — only differing by 0.1% — PSRC’s model apparently still incorporates the debunked claim that a failure to expand urban highways increases congestion, even if expanding them produces more driving. The Urbanist labelled this myth #1 on our list of five wrong planning claims around highway expansion that are causing the US to fail to make progress on its climate goals. The fact that the Puget Sound’s municipal planning organization is still presenting them as gospel is embarrassing.

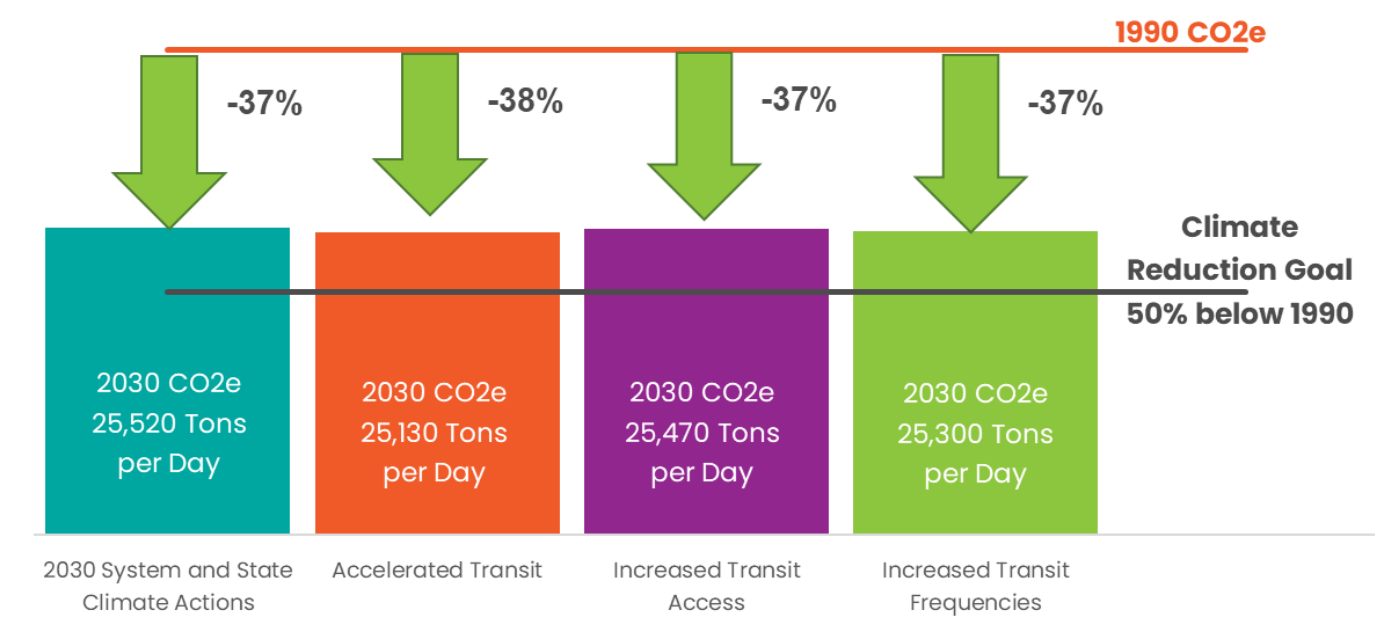

Transit Investments

On the transit side, PSRC’s models apparently show that increasing transit, in the form of accelerating transit investments, building more projects that increase access to that transit, or increasing frequencies on existing transit routes, do not move the needle much. This is not incredibly surprising in the context of how the models view roadway demand. The models assume current residents will continue to drive, while new residents concentrated around transit routes are the ones who will choose transit. An immovable volume of CO2 is already baked into the model.

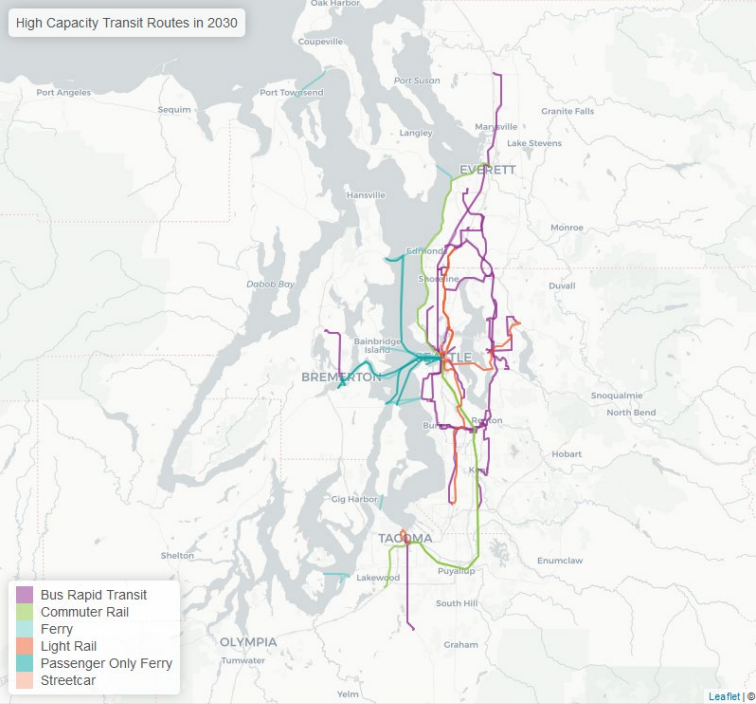

The 2030 transit network in the four-county region includes 21 bus rapid transit lines, at least one in each county, as well as 50 light rail stations and 7 passenger-only ferry routes. Hellman explained that the models showed no climate benefits because fewer people are projected to be living near those transit stations as a percentage of regional housing. “What we learned is, it makes a significant difference in 2050. And what we’re seeing is, the impact of the growth and accessibility improvements really matter about how many people we have living around these places….but we saw less of it in 2030, and part of that is where the growth is at,” Hellman said. “They all move in positive directions…they just don’t have as big an impact as we thought they would.”

Many of the assumptions behind the modelling done here are not known, and the relationship behind added roadway capacity and willingness to take transit when it offers an alternative to sitting in traffic is likely more complicated than this model is demonstrating. Clearly the leadership at PSRC can not disregard transit as an essential element in providing an alternative to the single biggest source of emissions in the region, private auto trips.

Road Charges

One way PSRC’s models did show that the outstanding emissions gap could be filled is by charging people to drive, via a per-mile road usage charge. But this model actually revealed that the adopted plan contains a massive flaw, an assumption built on a mountain of sand. The regional transportation plan currently assumes that by 2030 Puget Sound residents will pay a 10 cent per-mile fee to travel on the region’s roadways during peak hours, with that fee dropping to 5 cents off-peak.

But PSRC cannot adopt such a road usage charge (RUC) itself: the Washington State Legislature would. And right now the body moving forward with a pilot RUC is the Washington Transportation Commission, which is proposing essentially a direct gas tax replacement. That rate, of just under 4 cents per mile, is also recommended by the commission to remain fully earmarked for “highway purposes” in the same way that today’s gasoline tax is.

WSDOT Secretary Roger Millar offered the PSRC executive board a word of caution about assuming that a road usage charge would be both available for demand management and that the revenue could be used for general purposes. “We need to be keeping track of that, making sure that we don’t get boxed into a replacement for the gas tax that is as restrictive as the gas tax is,” he said.

If the usage charge moving foward at the state level is adopted, it would not only impact the revenue assumptions in the plan, it would also impact the climate model: the gap rises from 13% to 15% with a straight gas-tax replacement RUC and to 17% with no road usage charge whatsoever. This is a big flaw in the plan, given the lack of influence PSRC has over a road usage charge implemented on the state level.

Over the coming weeks, PSRC is planning to create additional modelling, “packaging” some of these potential changes together to see how they relate to one another.

King County Councilmember and current PSRC President Claudia Balducci noted that the work to analyze this emissions gap has a purpose, which is to directly inform the next round of funding recommendations as the agency fulfills one of its most important roles: divvying out federal funding. If the models show accelerating transit investments gets the region closer to its climate goals, there will be an effort to tilt funding in that direction. On the other hand, if the only things in PSRC’s models that make a dent in the emissions gap are entirely outside the agency’s control — like a Road Usage Charge, or vehicle electrification, or the rate of employees working virtually — then the boat doesn’t really need to be rocked.

“It seems likely that the lift to get to our 2030 goal is not as impossible as I maybe assumed it would be,” Balducci said. “But it’s not going to be easy.”