Last month, Seattle Neighborhood Greenways hosted our first 2024 Shaping Seattle event, Building Great Streets. More than 130 community members gathered at Town Hall Seattle to hear presentations from Laura Jane of HUB Cycling and Jean Beaudoin, Nomade Tactical Urbanism about transforming streets in Vancouver to boost cycling usage and in Montreal for summer enjoyment.

The event left us feeling energized and inspired to share several important takeaways.

Meaningful change takes sustained advocacy, support

Vancouver’s increase in cycling mode share didn’t happen overnight. It was a multi-year endeavor that initially faced steep uphill conditions.

As Jane mentioned during her presentation this can be seen most clearly through the history of the Burrard Bridge which connects many of the city’s neighborhoods to Downtown Vancouver. The first protected bike lane on the bridge was installed as a trial in 1996. However, it only lasted about a week before being removed due to significant opposition from some groups.

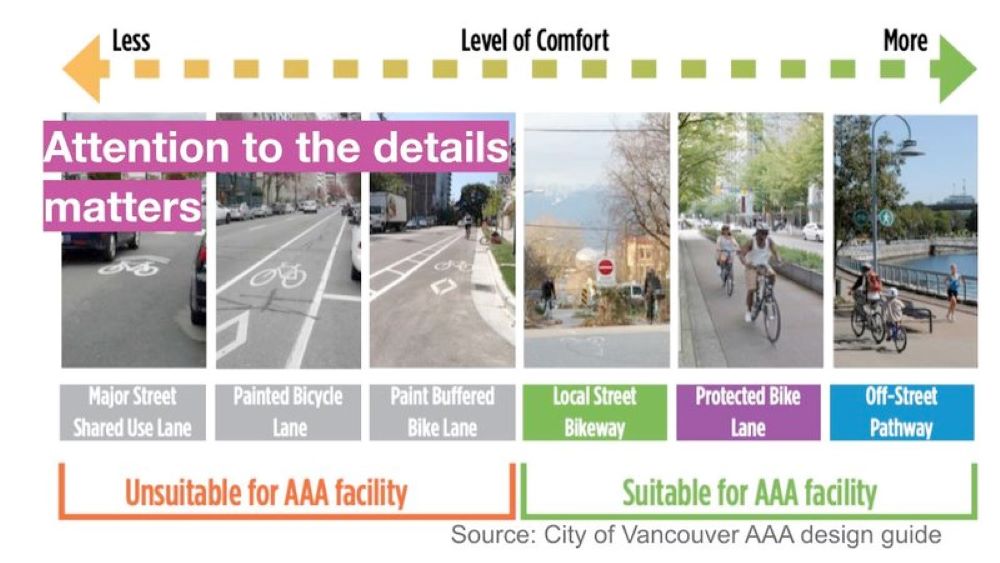

It wasn’t until 2008 when a new mayor and council majority were elected who were committed to advancing cycling infrastructure that Vancouver started to see major traction. One of the new government’s first acts was to bring back the protected bike lane plan for the Burrard Bridge. This time it was implemented as a pilot project with protective barriers and traffic signal modifications. It proved very successful and now has over 1 million annual riders today.

The success of the Burrard Bridge protected bike lane helped pave the way for additional protected bike infrastructure downtown and signaled a shift toward prioritizing cycling in Vancouver’s transportation planning.

Building on the success of the Burrard Bridge protected bike lane, Vancouver embraced a “carrot, stick, and tambourine” framework similar to Copenhagen to create a multifaceted approach to build infrastructure, create disincentives for driving, and build community engagement around cycling.

Some “carrots” used by Vancouver included investments in a connected citywide network of safe, protected cycling infrastructure. “Sticks” took the form of parking fees and limiting car access in densely populated areas making driving less convenient than biking for some trips. Finally, “tambourines” used to cheer on the success of biking involved marketing the idea of biking, creating events and programs celebrating cycling culture, and making it look easy, social, and fun.

All played a role in Vancouver’s success in doubling its cycling rates.

Tactical urbanism allows cities to test and build transformative projects

Montreal has developed the most exciting pedestrian streets program in North America by embracing experimentation and creating an iterative process of evaluating pilot projects to refine solutions based on community feedback over time.

During his presentation, Beaudoin discussed a few different tactics and projects that have helped activate public spaces on streets in Montreal.

Many of Montreal’s beloved streets are a result of tactical urbanism projects that temporarily close streets to create car-free zones for events, festivals, and activities during the summer. For many people, this serves as an introduction to the concept of people streets, changing their perception of what’s possible.

These temporary street transformations typically include programming like DJs, bike courses, street toys, and games to encourage new uses of the spaces beyond driving. To further designate the streets as places for people to gather rather than just for vehicles to drive, movable furniture, street art, and green space is added to transform the space into a linear park.

By testing changes through tactical, temporary projects and adding amenities, Montreal was able to activate streets and start shifting perceptions of their purpose and potential uses.

Partnerships are key to driving progress

Partnerships across sectors played a vital role in helping both Vancouver and Montreal make meaningful progress in transforming city streets to better serve people walking and biking.

In Vancouver, a sustained collaboration between advocates, government agencies, and the business community was instrumental in doubling the city’s cycling rates over decades. Groups like HUB Cycling worked closely with municipal departments to plan infrastructure investments and pilot innovative programs. They also partnered with the Downtown Vancouver Business Association, initially opponents but later supporters, through events celebrating cycling culture. This diverse coalition distributed both the responsibilities and rewards of ambitious goals.

Similarly, Montreal saw the power of partnerships mobilizing street-level change. Nomad Tactical Urbanism coordinated closely with local business improvement areas (BIA), who took the lead in implementing temporary projects testing new designs. The BIAs deep community relationships and expertise in navigating the local context empowered nimble, locally-driven solutions. While seeking more direct city involvement, Beaudoin recognized BIAs vital grassroots knowledge. Montreal’s collaborative, cross-sector approach distributed capacities for agile project management.

Data also strengthened these partnerships, with research institutions joining initiatives. Vancouver leveraged market studies to shift planning priorities, while Montreal explored integrating university evaluations.

Both Vancouver and Montreal demonstrate how embracing partnerships across advocacy groups, businesses, government agencies, and community stakeholders cultivates the will and capacity to transform streets.

Staying resilient through shared goals

As cities work to transform streets, setbacks will arise. But keeping focus on the big picture goals sustains resilience through difficulties. Both Vancouver and Montreal demonstrate how commitment to climate action, livability, and equitable development provides ballast.

Vancouver doubled cycling through sustained advocacy and policy changes over decades. This arose from recognizing transportation as a top climate issue, with goals to shift trips from vehicles. Even initial delays in installing protected lanes like on Burrard Bridge did not deter this long-game approach.

Montreal cultivates resilience through temporary projects testing ideas. But groups like Nomad Tactical Urbanism stay driven by a vision of streets as public spaces beyond mobility alone. They view tactical urbanism as one step toward climate-resilient, community-centric development.

And both cities emphasize partnerships as fortifying resilience. Cross-sector coalitions distribute responsibilities for ambitious goals. Montreal’s BIAs take lead roles with mayoral support, showing collaboration strengthens the capacity to withstand challenges.

By keeping sight of the big reasons for change – like climate, health, and livability – cities can persevere through setbacks. Shared goals of building complete, people-centered places that support sustainability and equity provide ballast. With commitment from communities and leadership, resilience endures to advance progress street by street.

Conclusion

Join us as we take these lessons learned and work to create a pedestrian street in the heart of every neighborhood and connect every neighborhood with safe and convenient bike routes.

A special thank you to Donna Moodie (Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle) for being our moderator for the afternoon.

And finally a big thanks to our sponsors and community members for coming together for an afternoon of learning about how Seattle can build great streets for people to bike and enjoy. Building Great Street was sponsored by Amazon, Washington Bike Law, Seattle Department of Transportation, Fleming Law, Lime, Commute Seattle, LMN Architects, and Site Workshop.