The interstate is dead. Long live the spurs.

As we work towards resolving the fate of highways in Seattle, there is some administrative closet cleaning to be done. We cannot break Interstate 5. As the primary thoroughfare for the West Coast, I-5 must be continuous from Canada to Mexico. It’s the way the Interstate Highway Defense Act designed the highway system, and the way funding and designations have been set up for 70 years. This is the way.

Does that mean all hope of reimagining the city’s relationship with the highway is lost? No. We have an alternative. We should change the highway names. Designate what is now Interstate 405 as the primary highway–as I-5–and rename all of the roads leading into the city. That way I-5 can remain continuous while we make decisions on what is to be done with the roads running through Seattle.

But what should the roads coming into the city be called? The easiest would be a simple switch to make the downtown stretch into a new I-405. However, that still forces the road to be continuous because of tradition. Making real change requires knowing a little more about how we identify highways.

Numbers game

As interstate highways stretched across the country, a numbering scheme was developed. There are some exceptions, but for the most part, the large grid of super roads is very regular.

Odd numbered highways run north-south. Even numbered highways run east-west. The big roads that run coast-to-coast or border-to-border get numbers divisible by 5. And all the numbering starts in the southwest and runs northeast. That pretty much explains why Seattle is at the intersection of Interstate 5 and Interstate 90. We’re far west, so the north-south number is low. We’re far north, so the east-west number is high. For the other corners, I-5 and I-10 meet in Los Angeles; I-95 and I-10 meet in Jacksonville; and I-95 and I-90 meet in Boston. If you have not driven these intersections, I can tell you from experience that they are every bit as scenic as you can imagine. None of these freeway interchanges belong in a downtown.

Also for the Interstate System, it matters whether a highway number is two- or three-digits. The two digits are the main roads, like I-90 and I-5 (think of it as I-05). The three digit highways are spurs and beltways off of those two digit roads. If the three-digit highway starts with an even number, it intersects its parent road twice. If it’s an odd number, the three-digit road is a spur that intersects only once. That’s how we can tell Interstate 405 will exit I-5 and come back around to rejoin it further along, while Interstate 705 in Tacoma exits the primary road as a spur into the city with no second connection.

One last thing with numbers, highway exits matter. The mileage numbers start in the southwest of each state, echoing the highway system as a whole. In most states, highway exits are based on that mileage. We know that I-90 is about 164 miles from the Oregon border because it is Exit 164 off I-5. It works because Interstates are supposed to be limited access, with no more than one exit per mile–I-5 breaks this convention in Downtown Seattle.

Three Spurs: I-105, I-905, and I-590

Given I-405 is a three digit highway that starts with an even number, convention dictates it must be continuous and attach to I-5 at two points. That means simply swapping I-5 and I-405 does nothing substantial. To have an opportunity to do something truly novel, let’s drop I-405 and play with the numbers in a way that sets us up for transformative improvements. Let’s redesignate I-5 through Seattle in a way that shows we are hacking back the invasive highways that have strangled our city.

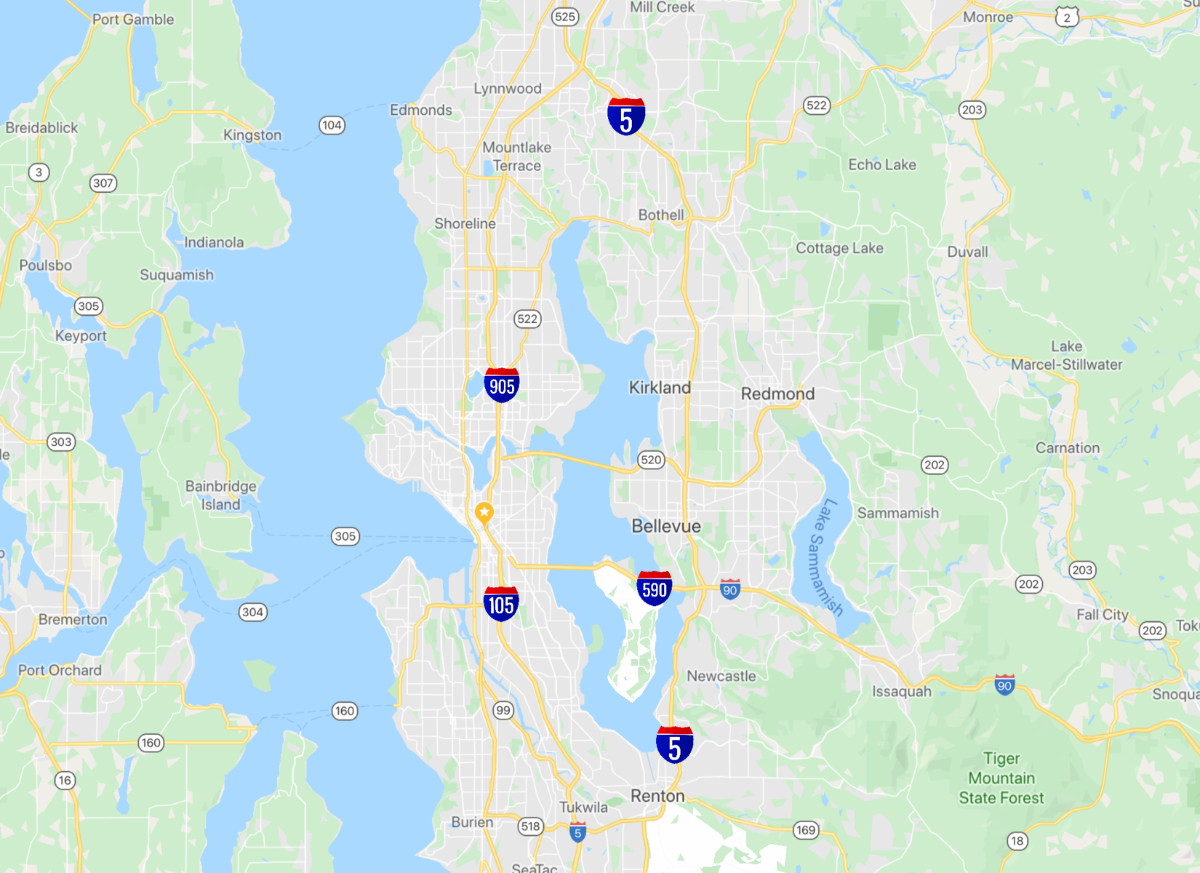

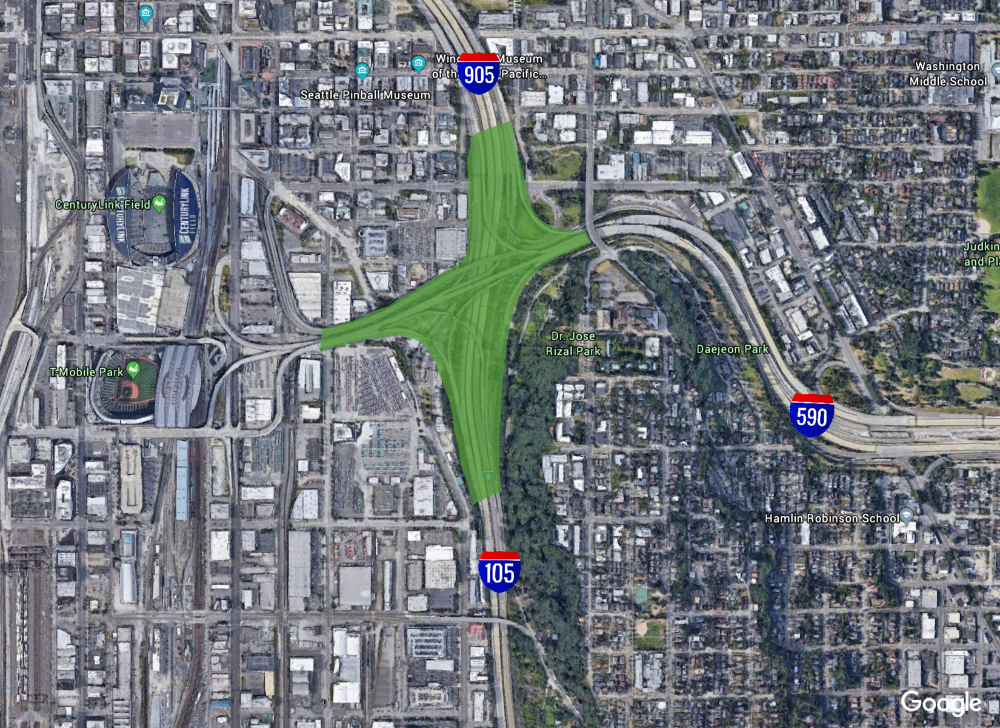

From the south, we will designate Interstate 105 to go from Southcenter towards the Port and the Duwamish industrial area. From the north, we will designate Interstate 905 coming from Lynwood to the University District.

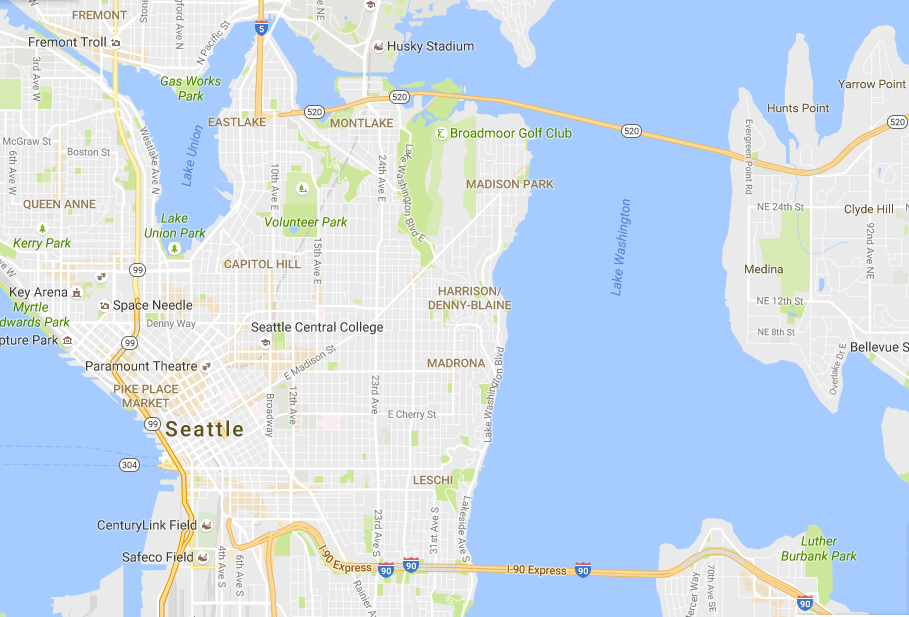

And without I-5 running through Seattle any more, we can make one more change. A new milemarker 0 for Interstate 90 will be in Factoria. A newly designated spur, Interstate 590, will go west from there, crossing Mercer Island and going towards downtown.

Changing highway designations has been done elsewhere. For many years, I-95 around Princeton, New Jersey was discontinuous. You stayed on I-95 north through Pennsylvania, but then crossed into New Jersey and all of the sudden the signs informed you that you were on I-295 southbound. Then you got yourself back onto I-195 and I-95 again. (Alternately, you just paid to get on the Jersey Turnpike). Using the last money from the Interstate Highway Act of 1958, Pennsylvania and New Jersey built a new flyover that made the connection direct. In the process, portions of former I-95 were redesignated I-295.

Also in the east, the Iway project in Providence created a new intersection between I-195 and I-95 and rerouted the spur southward. This eased what was once a jagged chicane through the city and opened up 44 acres of developable space.

What it would take

As with everything in the Interstate Highway System, there is a process to redesignate or remove highways. It’s laid out in Appendix D of 23 U.S.C. 103(b) where the Secretary of Transportation may approve a highway change based on findings that include assessment of need (freight and traffic volumes), connection to existing highways and intermodal facilities, and adoption as part of a regional transportation plan. Most of these have to do with the addition of highway routes.

The only place where the criteria talks about removing a route says, “Proposals should include information concerning the possible effects of adding or deleting a route to or from the NHS might have on other existing NHS routes that are in close proximity.” So we don’t get to talk about benefits like noise abatement, reduced emissions, or removing a deep wound through the city. We have to talk about traffic, and not even actual traffic, but “possible effects” traffic.

The proposals don’t get sent to the Secretary of Transportation by Seattle or King County. They get sent by the designated “Metropolitan Planning Organization.” For us, this is the Puget Sound Regional Council. PSRC has a mixed reputation on visionary-ness. They are the stewards of managing growth within the Growth Management Area. They are also devoutly attached to a strict hierarchy of roads, centers, and development areas that reinforces municipal competition and keeps a lot of the region in single-family-detached houses and thus a lot of traffic on the road. Adjusting the highways goes through PSRC.

Why even try?

It’s as if the slightest change to a highway is vastly more difficult than it was to build the road in the first place. Why is it at all important to do something small and silly, like changing the highway name?

Technically, redesignating I-5 to the outside of the city takes the onus off the highways in the city. Entering the city as spurs, the three roads coming into downtown can stop pretending to be superhighways. All of the left turns, merges, and exits from the West Seattle Bridge to 45th Street north of Portage Bay are noncompliant for an interstate. If we stop considering this a massive through corridor, imagine how much more creative can we be designing roads that function. Breaking up the downtown highways breaks us out of highway thinking and allows us to solve real problems on the ground without preconceived results.

More importantly, redesignating the roads changes the story. As a regional narrative, there is Seattle and there is the Eastside echoed in the parallel highway and bypass we currently have. Disconnecting one of those parallels and relying on other parts of the region will shift a lot of balances. What changes when our roads become radials instead of parallels? I honestly cannot say, but it’s going to be an intensely interesting thing to figure out.

And we need a change of story because pushing an Interstate outside of the city is far too rare. Really, the only example of where it happened is the other Washington. While I-95 runs through the downtowns of most east coast cities, our nation’s capital is bypassed. Only spurs of 95 go into the city at I-395 and I-695. For DC, keeping the highway out was the crux of their 1950’s highway revolt. Citizens in the District rejected plans to extend I-95 from College Park, Maryland into downtown. After years of contentious fighting, plans for the North Central Freeway were dropped, preserving neighborhoods throughout Northeast DC. Unfortunately, this one good example took place before the road was built. In Seattle, freeway revolts did limit further freeway expansion plans, sparing the Central District.

Now we have to figure out what to do with massive infrastructure that costs a ton to upkeep, regularly fails to serve the purpose for which it was built, and frankly makes everyone around it sick. We need to change the narrative about highways, put them into a place where the roads serve people instead of the city contorting around oversized and barely functional infrastructure. Reimagining Seattle’s highways starts with renaming them.