Seattle’s comprehensive plan promises to build more housing along frequent transit corridors, without offering many details on where that housing would be located. Based on an analysis of draft zoning maps, I found that within the low-density residential neighborhoods that cover most of Seattle:

- The comprehensive plan would upzone fewer than 1 in 10 parcels within a five-minute walk of transit stops.

- Almost all of the added capacity would be concentrated along hazardous arterial streets, without specific commitments to safety improvements along those streets.

Seattle deserves smarter and safer growth along our transit corridors.

The One Seattle Plan’s arterial rezones

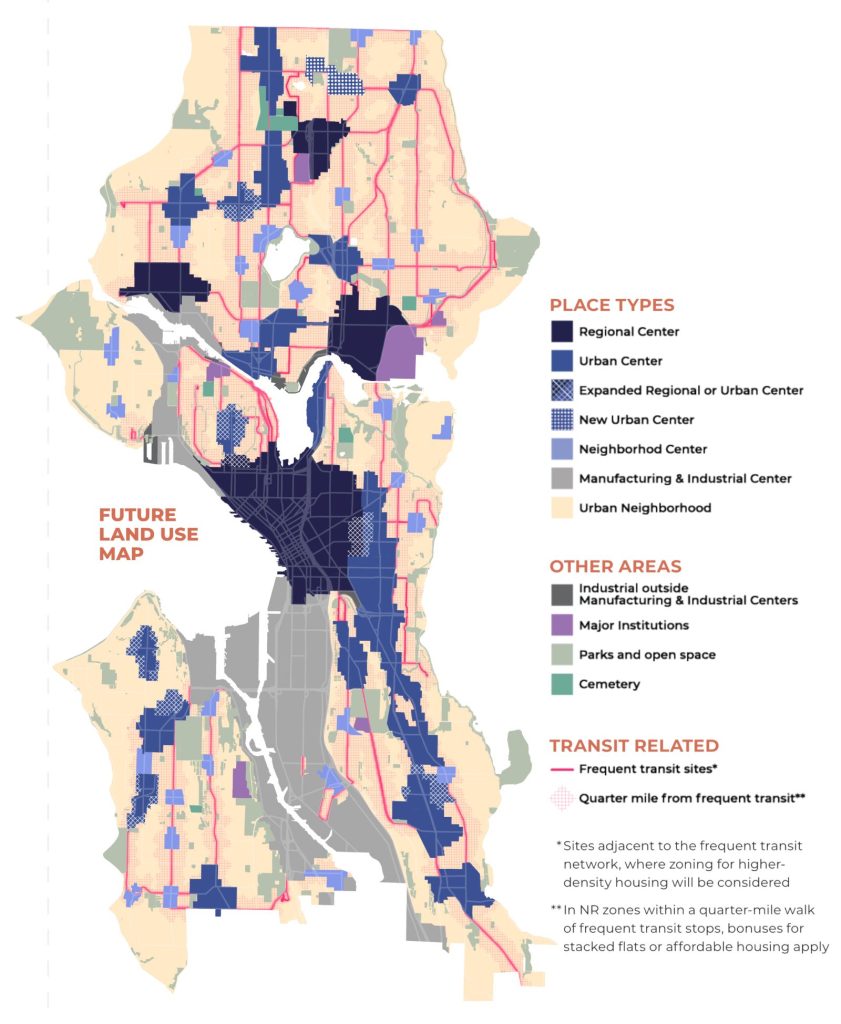

Seattle’s comprehensive plan is finally headed to City Council this May in the form of draft zoning legislation. As both an important policy document and a proxy for fundamental debates about Seattle’s future, the One Seattle Plan has sparked passionate discussions over the past two and a half years of community engagement.

Since 2022, The Urbanist has shared viewpoints about the plan’s many downstream effects, ranging from Seattle’s supply of accessible and affordable housing to the health of our orcas and tree canopy. These conversations are most productive when the city has laid out a well-defined proposal that the public can react to: for example, after the draft comprehensive plan laid out specific boundaries for 30 proposed Neighborhood Centers, that list became one of the most-discussed items at the plan’s first public hearing in February.

Compared with new Neighborhood Centers, the implications of “select arterial rezones along frequent transit routes” have received far less media attention. How should we interpret the scope of the planned rezones along these routes?

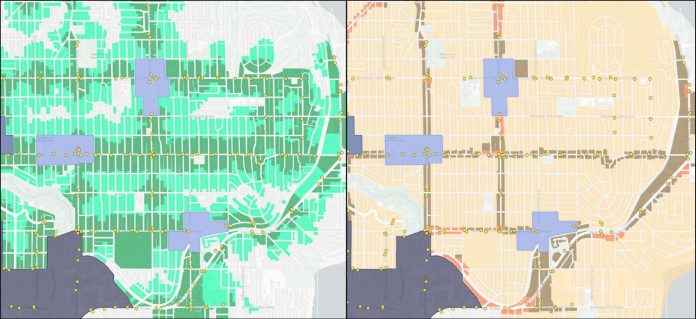

To answer that question, I created side-by-side maps that compare access to transit with the One Seattle Plan draft zoning map, released in October 2024. At the top, you can toggle between different types of transit routes:

- Service Frequency: Filter to routes with 15-minute frequencies or better during peak commuting hours (7-9 am and 5-7 pm)

- Route Connections: Filter to routes that connect to downtown Seattle, any Regional Center (including downtown), or the light rail

Your selections control two maps below:

- Proximity to transit: This map shows parcels within a five-minute walkshed of transit stops on the selected routes. Selected transit stops are shown as yellow dots; parcels within a two-minute walkshed are highlighted in dark green; and parcels within a three to five-minute walkshed are highlighted in light green.

- One Seattle Plan proposed zoning: This map shows the proposed future zoning for each parcel as of October 2024. You can mouse over or tap on the map to see the current zoning and proposed future zoning for that parcel.

These interactive tools show proposed zoning changes in “Urban Neighborhoods,” the City’s designation for formerly single-family neighborhoods, which will soon allow a wider range of housing options thanks to statewide zoning reform. The tools exclude blocks already contained within Regional Centers, Urban Centers, or Neighborhood Centers. Industrial zones and publicly-owned parcels are also excluded.

To summarize these maps, I’ve also created an interactive table showing the current and future zoning for residential parcels in Urban Neighborhoods within a five minute-walk of transit stops. These include:

- Neighborhood Residential (NR), the least dense zone. Residential Small Lot (RSL) zoning is also grouped into this category.

- Lowrise or Mid-rise (LR/MR) zones

- Neighborhood Commercial or Commercial (NC/C) zones.

Pay close attention to the top row of data: this summarizes how parcels near transit that are currently in the lowest density group will be handled under the proposed rezone.

I hope these maps help clarify the city’s proposed rezoning plan for frequent transit corridors. To lay out the policy clearly:

- Within Urban Neighborhoods, the city’s proposal upzones less than 10% of Neighborhood Residential parcels within a five-minute walk of transit stops. This is equally true whether we consider all transit routes or frequent transit routes connecting to downtown.

- Almost all parcels being upzoned are located on arterial streets.

What are the problems with this plan, and what might an alternative look like? To clarify, let’s examine a model Urban Neighborhood along a transit corridor.

One neighborhood, four possible futures

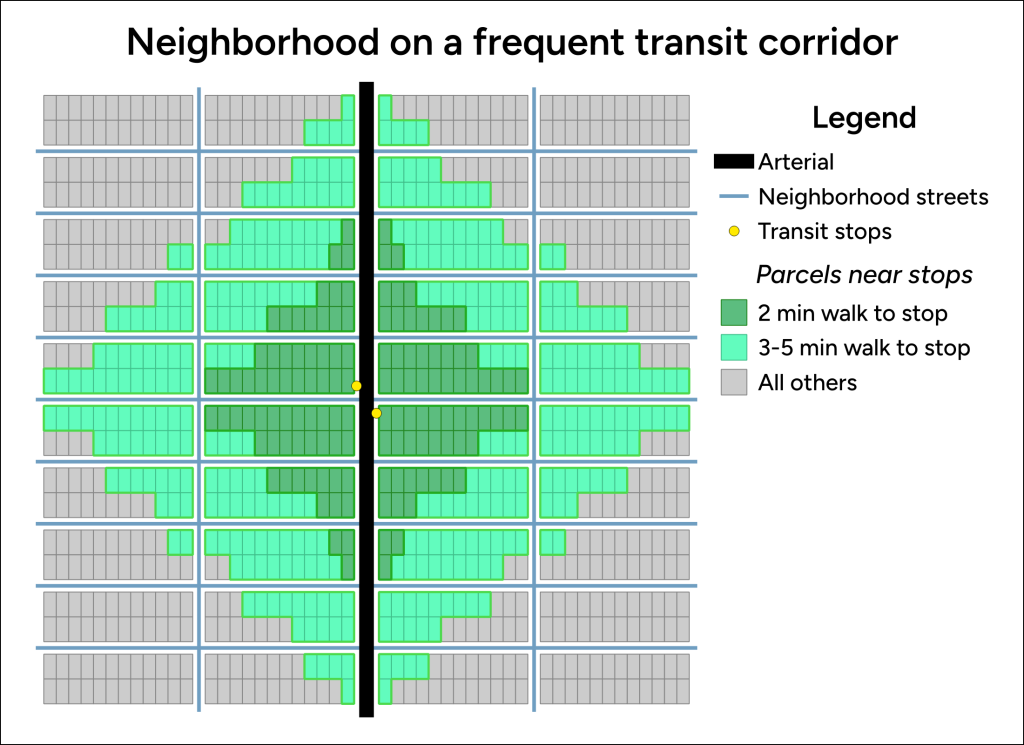

Consider the example neighborhood in the image below.

The neighborhood is like many low-density residential zones of Seattle: each residential parcel has an area of 5,000 square feet, and 24 parcels make up one block. There are 40 blocks in this model neighborhood, so the neighborhood has a total of 960 (24 * 40) parcels.

An arterial runs north-south through the neighborhood. A transit route runs along the arterial and stops at the central intersection in the neighborhood. Out of all the residential parcels, 132 (14%) are within a two-minute walk of a transit stop, 484 (50%) are within a five-minute walk of a transit stop, and 40 (4%) are along the arterial.

Without targeted safety improvements, living directly alongside an arterial street can be hazardous to your health. The 2023 Vision Zero Review conducted by the Seattle Department of Transportation found that 93% of pedestrian deaths occur on Seattle’s arterial streets. People living along arterials may be at risk for unhealthy levels of air pollution, particularly during commuting hours when traffic volume is highest; they are also more exposed to harmful levels of noise pollution from speeding traffic. Given those hazards, we might conclude that a sensible approach to transit-oriented development policy adds housing near transit while reducing risks from the arterial.

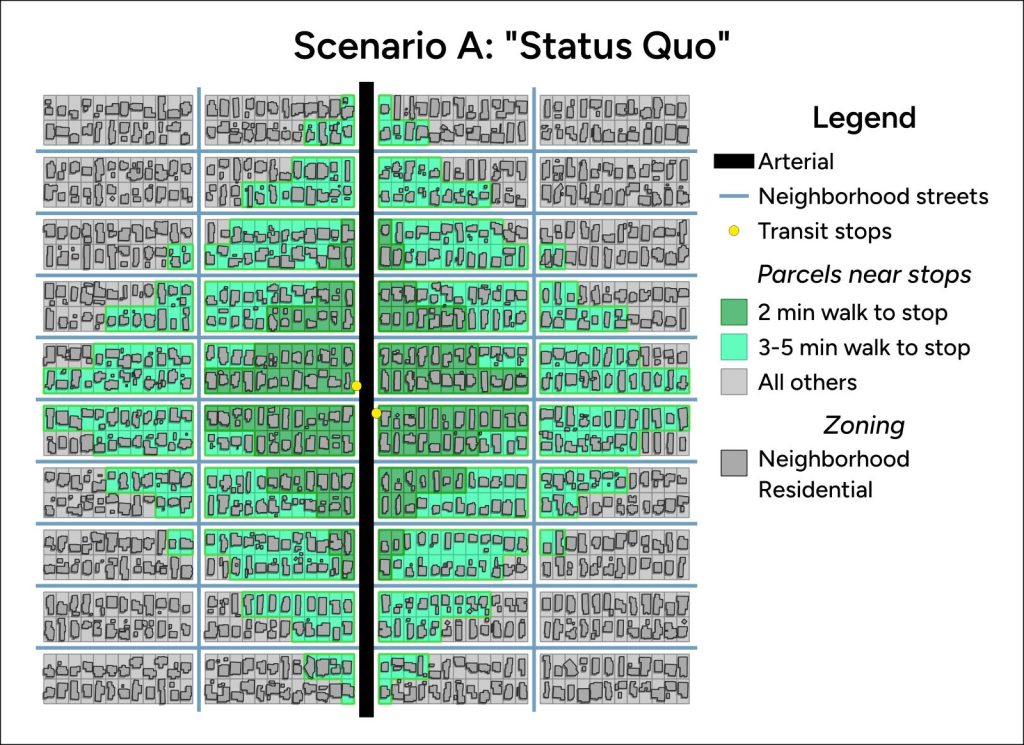

Present day: mostly single family housing

Most residential land in Seattle is zoned Neighborhood Residential (NR), the least dense zoning designation with single family residences on most lots.

Under this uniform zoning, the distribution of housing capacity matches the distribution of parcels: about 320 people (14%) live within a two-minute walk of a transit stop, 1,160 people (50%) live within a five-minute walk of a stop, and 100 people (4%) live along the arterial.

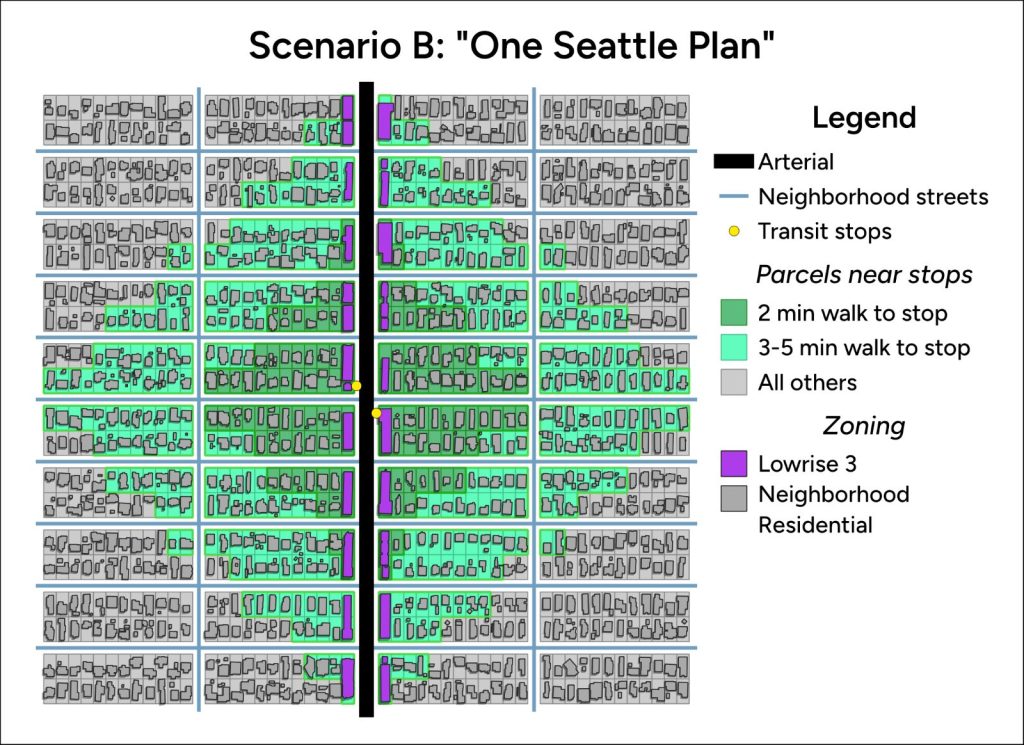

The One Seattle Plan: upzoning only on the arterial

Under the city’s current proposal, the 40 parcels directly along the arterial would be upzoned to Lowrise 3, creating a thin strip of land with up to six-story apartment buildings, while all parcels off the arterial would remain Neighborhood Residential.

If fully built out, this plan would increase the number of people living within a two-minute walk to a bus stop (about 510 people, or 19% of total) and a five-minute walk to a bus stop (1,480 people or 56%). On the other hand, this plan maximizes the proportion of people living along arterials: about 420 people (16%) would be exposed to the hazards of living along the busier street.

Note that a full build-out scenario takes a long time to occur, and almost certainly falls outside the 20-year timeframe of the One Seattle Plan. Redevelopment depends on the property owner selling, a homebuilder buying, and that homebuilder successfully navigating the permitting, financing, and construction process. For the 20-year window of the plan, only a fraction of parcels are likely to redevelop to their new zoned capacity.

Spreading housing capacity thinly along the arterial creates other downstream problems for planning: there is no obvious focal point for a local corner store to open, or for SDOT to prioritize new street safety infrastructure.

New housing close to transit

During public engagement for the comprehensive plan, community feedback noted the downsides of the arterial-only proposal and suggested a different approach:

Many comments called for a more geographically extensive approach toward adding density along bus transit corridors that does not restrict upzones to locations that are directly on the arterial and would include wider corridors that extend a block or further from the transit route. Many called for allowing midrise development within a quarter mile of frequent transit, as noted on page four of the City’s Draft Plan Engagement Summary.

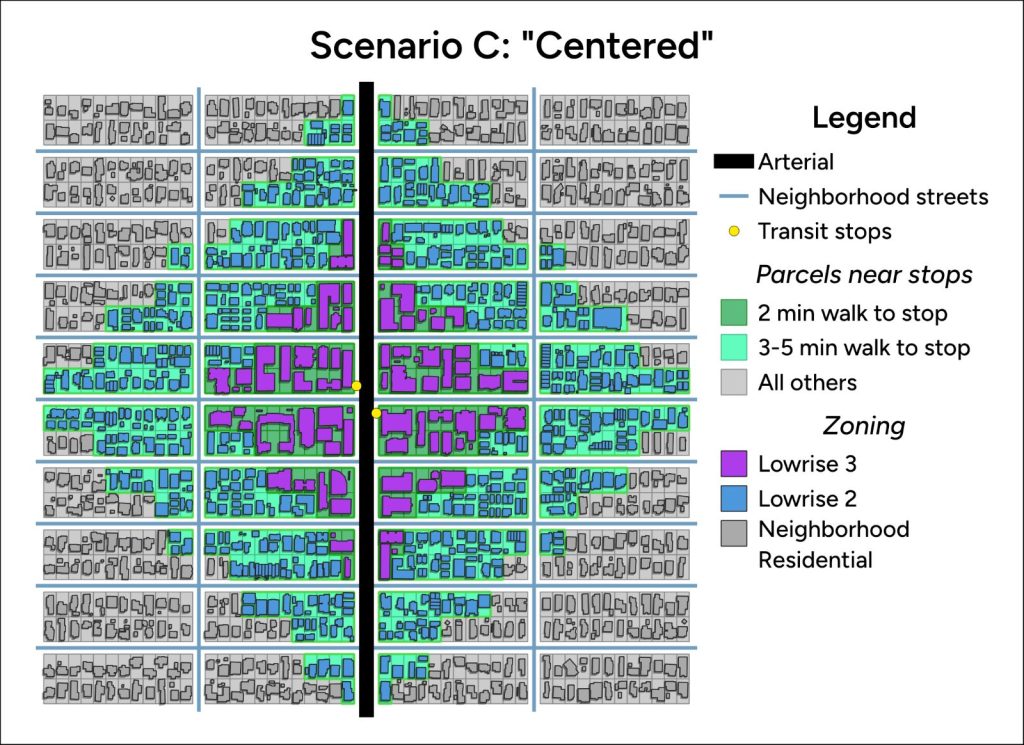

The map below gives an example of what access-based rezoning could look like in our model neighborhood. Parcels within a two-minute walk of a transit stop have been zoned Lowrise 3, and the remaining parcels within a five-minute walk of a transit stop have been zoned Lowrise 2. All parcels outside of the five-minute walkshed retain Neighborhood Residential zoning.

Compared to the city’s rezoning plan, this scenario nearly triples the number of people who can live within a short walk of a transit stop. If fully built out, about 1,380 people (25% of total) would live within a two-minute walk of a transit stop, and 4,290 people (79% of total) would live within a five-minute walk. Within a five-minute walk of the transit stops, nine out of ten homes would be located on quieter neighborhood streets.

The graduated zoning in this scenario centers the neighborhood around the transit stops. This creates a focal point for other investments in the neighborhood, some of which are explored in the scenario below.

A thriving five-minute neighborhood

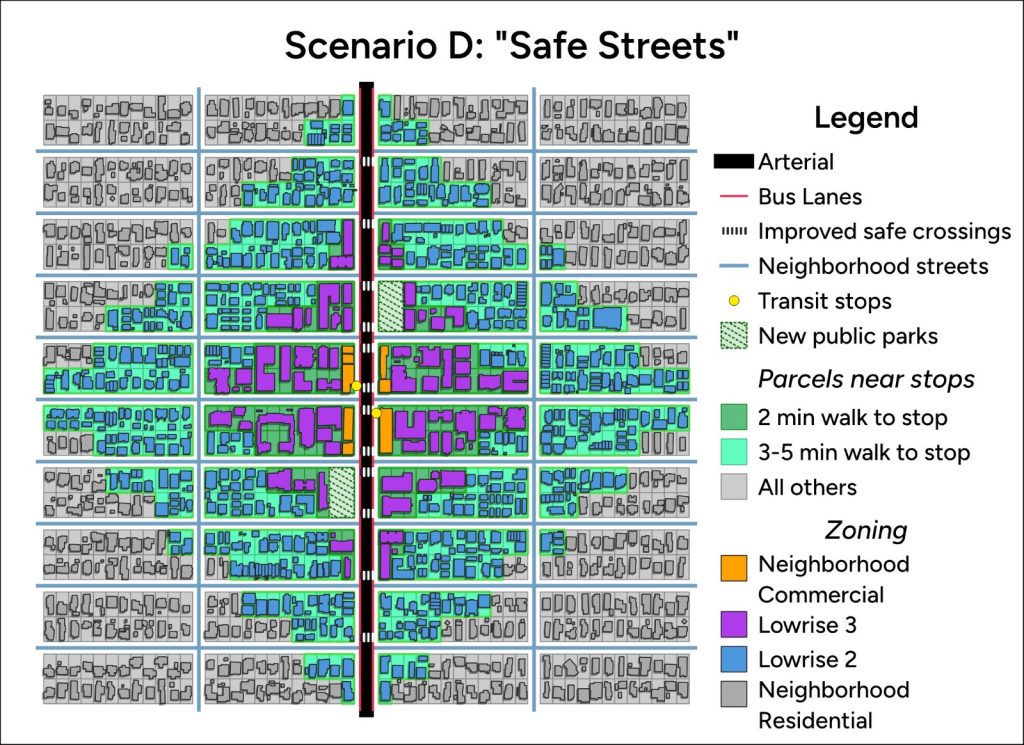

Finally, let’s consider how centered residential density could be paired with targeted safety improvements and new amenities along the arterial street. This plan makes three changes to the previous scenario:

- Centered neighborhood commercial: The two blocks closest to the transit stops along the arterial are rezoned to Neighborhood Commercial, creating space for new pedestrian-oriented local businesses

- Parks: The city invests in two half-acre parks to serve the neighborhood

- Arterial safety features: Improved pedestrian crossings, bus lanes, and other traffic calming features prepare the arterial for greater pedestrian use

This scenario houses many more people near transit than the status quo or the One Seattle Plan: if fully built out, about 1,410 people (26% of total) would live within a two-minute walk of a transit stop, and 4,330 people (79%) would live within a five-minute walk. Because Neighborhood Commercial zoning allows for housing above street-level retail, this scenario actually includes slightly more housing along the arterial than previous options (about 470 people or 8%), despite some arterial parcels being reserved for parks.

Compared to previous examples, this scenario also improves the quality of life along the arterial. New road safety features enable safer pathways for pedestrians; they also hamper speeding, reducing noise pollution along the arterial. New public green spaces improve air quality, cool the neighborhood on hot summer days, and offer city officials another tool to increase local tree canopy. Locals benefit from new neighborhood businesses and public spaces, and their trips to those amenities encourage lively, pedestrian-oriented streets.

Seattle deserves safe streets and convenient commutes

Let’s compare the headline numbers from these four scenarios in our 40-block test case:

| Scenario | Population in model neighborhood | |||

| ≤2-minute walk to stop | ≤5-minute walk to stop | On arterial | Total | |

| A: Status Quo | 320 (14%) | 1,160 (50%) | 100 (4%) | 2,300 |

| B: One Seattle Plan | 510 (19%) | 1,480 (56%) | 420 (16%) | 2,620 |

| C: Centered | 1,370 (25%) | 4,280 (79%) | 380 (7%) | 5,430 |

| D: Safe Streets | 1,410 (26%) | 4,330 (79%) | 470 (8%) | 5,470 |

A quick note on zoning math: my assumptions about units per parcel roughly match Seattle’s Zone Development Capacity Model, and my average household sizes correspond to ACS five-year (2019-23) estimates for Seattle, assuming that most NR households own, most LR3 and NC households rent, and a 50-50 split in LR2 households.

| Zone | Avg. units per parcel | Avg. people per household |

| Neighborhood Residential | 1 | 2.40 |

| Lowrise 2 | 4 | 2.07 |

| Lowrise 3 | 6 | 1.73 |

| Neighborhood Commercial | 15 | 1.73 |

You could tweak those capacity assumptions or propose different zoning near transit, but this article’s key points hold true regardless:

- The One Seattle Plan’s current plan for rezoning transit corridors maximizes the number of people exposed to arterial hazards.

- A centered approach based on travel times to transit stops would house more people on safe neighborhood streets.

- Upzones near frequent transit corridors should be paired with a plan to invest in pedestrian safety infrastructure along those corridors.

You might also object that the transit routes I highlighted are unworthy of new housing—maybe they’re not frequent enough for your liking, or the connections are insufficiently direct. Whenever I hear that flavor of objection, I’m reminded of all the congested, multi-hour driving commutes into Seattle. How many people would jump at the chance to live in new housing a single bus ride away from their job, if we would only legalize that housing? How many tons of future carbon emissions do we lock in by pricing people out of the city where they work?

The final comprehensive plan should clearly articulate the strategy for rezoning along transit corridors and explain how that strategy is consistent with the city’s health equity and Vision Zero goals. Seattle’s Office of Planning and Community Development has not yet released new zoning maps to accompany Phase 2 zoning legislation (which has been promised in May), so there is still an opportunity for the city to improve its plan for transit corridors.

If you feel strongly about how Seattle’s transit corridors evolve over the next 20 years, email your City Council representatives at council@seattle.gov to request that the One Seattle Plan adds more housing capacity on safe neighborhood streets near transit stops, not just along arterials.

Nat Henry is a professional geographer based in Seattle. He runs Henry Spatial Analysis, a mission-driven consulting firm focused on health and urban sustainability.