The bill provides a strong template for allowing housing near high capacity transit, but does not kick in until 2029 in central Puget Sound.

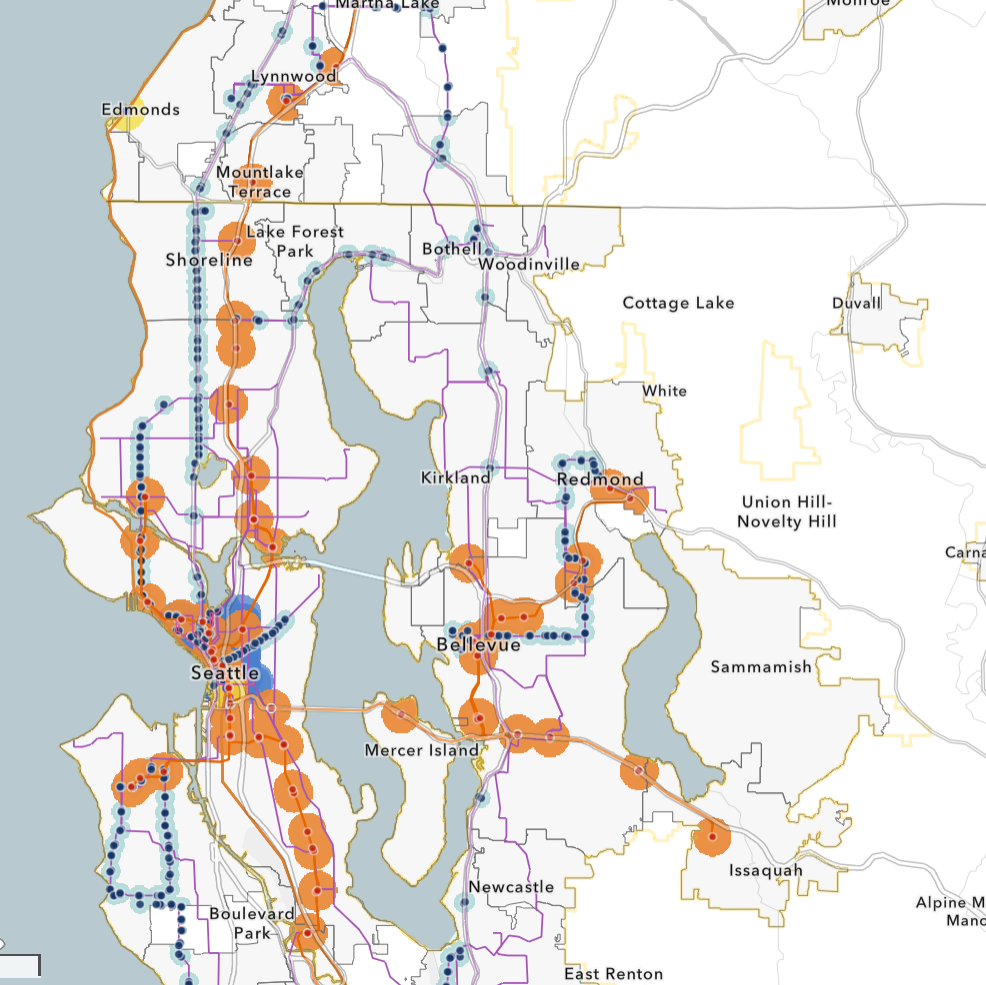

On Tuesday, the Washington State Senate approved a bill queuing up significant zoning changes around light rail stations, commuter rail stations, and bus rapid transit stops. The framework outlined in the bill is poised to lead to tens of thousands of new homes near transit, though a phased implementation schedule will mandate those zoning changes gradually.

Yonah Freemark, a researcher with Urban Institute, noted Washington’s bill would be a “very substantial” expansion of zoning capacity in a Bluesky post. “It would be one of the largest state-sponsored upzonings ever in the US,” Freemark added. In 2023, Freemark authored a report that laid out the housing capacity such a bill could unlock in the region.

House Bill 1491, sponsored by Rep. Julia Reed (D-36th, Seattle), represents the culmination of three years of work to find a framework for transit-oriented development (TOD) that the two legislative chambers could agree upon. The state House already approved the bill in early March. The two chambers will need to reconcile their respective bills after the Senate amendments.

“In the last couple years, we’ve made some really significant progress on things like legalizing accessory dwelling units, co-living spaces, middle housing,” Senator Jessica Bateman (D-22nd, Olympia), chair of the Senate’s housing committee, said Tuesday. “But if you talk to the experts, they will tell you that those solutions, while important and nimble and flexible, really are not going to allow us to gain the economies of scale that we need if we’re going to actually build one million homes over the next 20 years. That’s where this bill comes in.”

The Washington TOD bill is complicated and applies unevenly throughout the state, but it would nonetheless represent a large upzoning through many municipalities throughout the Puget Sound, as well as in Spokane & Vancouver WA. It would be one of the largest state-sponsored upzonings ever in the US.

— Yonah Freemark (@yonahfreemark.com) April 15, 2025 at 3:58 PM

Under HB 1491, cities across the state will need to make room for larger apartment buildings within a half-mile of light rail, commuter rail, and streetcar stops, and within a quarter-mile of all bus rapid transit stops. More capacity for housing must be created near the rail stops, and cities can distribute that increased capacity equally, or concentrate it closer to the transit stations. Cities can exempt up to 25% of the stops around their bus rapid transit stations, but only if they allow additional density near the other stations.

The bill does not require immediate upzones around Sound Transit light rail stations and RapidRide stops. Because it follows the preset schedule for local update of Comprehensive Plans, HB 1491 won’t become mandatory in King, Snohomish, and Pierce County until the end of 2029. Comprehensive Plans see major updates once per decade, with a minor update at the halfway mark. Vancouver, with its Vine bus rapid transit system, will need to comply with the bill by mid-2026, with Spokane to follow by the end of next year.

If a transit-oriented development bill had been approved in 2023 — the original “year of housing” at the Washington legislature — then it likely would have prompted changes in the state’s most transit-rich places sooner. But the details of the proposal took longer to work out. When the Senate approved a TOD proposal that year, by a landslide 40-8 vote, it landed like a thud in the House because it didn’t include any mandate for developers to set aside affordable units in the resulting buildings. That requirement was seen as essential by many House Democrats to ensuring that lower-income people have access to amenity-rich areas near transit.

Yet the next year, when the House approved its counterproposal, which included a mandate for at least 10% of the units within station areas to be made available to lower-income households, it was not able to garner majority support in the Senate — in large part because that mandate was seen as a non-starter by Republicans and market-oriented Democrats in the legislature.

The bill was able to get across the finish line in 2025 thanks to a compromise. In HB 1491, the affordable housing mandate remains, but it’s paired with a tax exemption program, a move that ensures that developers aren’t being the ones asked to take the hit for a good everyone broadly agrees is needed: more housing near transit. High requirements without offsets could end up depressing homebuilding, rather than stimulating it, as intended.

This is where things get really wonky. Under current state law, cities are authorized to create a 20-year multifamily tax exemption (MFTE) program that provides a property tax break if a builder sets aside at least 20% of their units as affordable. Though the tax break lasts two decades, the units must be kept affordable for 99 years. But this bill creates a new 20-year program that only requires developers to set aside 10% of their units for 50 years. They can also choose to set aside 20% of their units as workforce housing, available to households making more modest incomes.

There are other incentives as well. Projects participating in the new MFTE program receive a 50% discount on impact fees, and builders can receive even more development capacity if they include more affordable housing than is mandated. Family-sized units (three bedrooms or more) are completely exempt from the density limits that apply to smaller units.

“This is a balanced bill that ensures that low-income people can be a part of the transit utopia we’re seeking to build while creating mixed-income communities where everyone can belong,” Rep. Reed said ahead of the bill’s passage in the House last month. “This bill ensures we’re getting the best return on investment for our most-used transit assets. But embedded in this dry text about zoning are the dreams of people like me, people in their 30s and 40s who dream of making a life in this state, in an affordable home in a vibrant mixed income community near family and transit assets that facilitate easy commutes. That’s the dream this bill seeks to realize.”

While HB 1491 will take a while to go into effect in Puget Sound, a last-minute amendment in the Senate could bring changes there sooner. A proposal by Senator Yasmin Trudeau (D-27th, Tacoma) directs the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) to pilot transit-oriented development on its existing park-and-ride facilities, including those along State Route 99 and I-405. That move could bring TOD to underutilized state land close to transit much sooner than the other provisions of the bill.

While it took a while to get everyone on the same page, HB 1491 seems to be a robust framework for transit-oriented development that everyone can agree on, and is poised to allow many more people across Washington State to live in affordable homes near transit.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.