After two councilmembers proposed a moratorium on most multifamily development, a proposal to implement affordability requirements moved forward instead.

The Woodinville City Council last week agreed to advance work on temporary zoning regulations that would require all new apartment buildings within the city’s downtown to set aside at least 10% of their units as subsidized affordable housing. Legislation is expected to be officially taken up by May and presumably propose a rent limit for the required “affordable” homes, which wasn’t yet discussed.

Councilmembers are framing the move as an attempt to ensure that new development in the city meets a baseline threshold for badly needed affordable units. But with such a quick process and so little in-depth discussion, the move appears to be more for show than anything else.

The discussion topic last Tuesday was initially scheduled to be a full moratorium halting building permits on all multifamily buildings in Woodinville, a request made by Councilmembers Rachel Best-Campbell and Al Taylor in mid-March. On its face, the moratorium was framed as a way to prevent projects moving forward without furthering compliance with the city’s affordable housing goals.

But the discussion quickly pivoted instead to interim zoning regulations, with numerous councilmembers pushing back on a full moratorium as an action that could chill the development environment in the city for years to come.

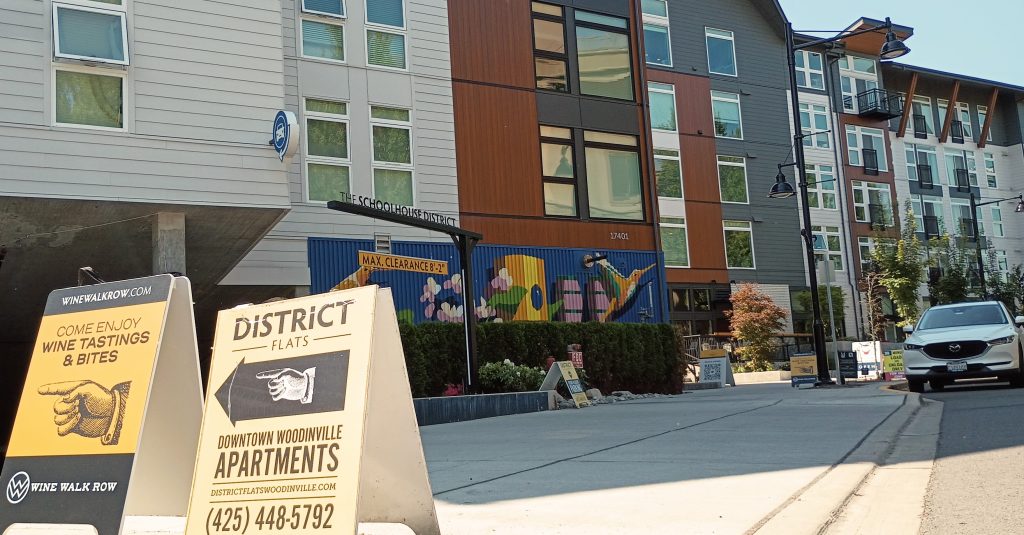

Woodinville’s downtown has seen a radical transformation over the past decade, with hundreds of units built and many more anticipated. But tensions have been increasing over the future direction of the city, with the generally pro-development council majority heading for a likely clash with those who see Woodinville transforming too fast.

A new political action committee (PAC) called “Democratic Woodinville,” which is funded primarily by Woodinville resident and tech worker Jeff Lyon, has been recruiting council candidates via mailers and billboards. Lyon’s group has been promoting a 26% affordability requirement for all development — a threshold so high it would likely be the same as imposing a moratorium in effect.

At the center of the debate is the former Molbak’s garden store property in downtown Woodinville. Green Partners, the property’s owner, has submitted initial plans to the city to turn the 19.2 acres it owns into around 1,300 units of housing along with a 200-room hotel and 89,000 square feet of retail space. But the company is seeking a development agreement, a site-specific plan for its property that will get individual buy-in from the council and will likely include a specific number of affordable units. Whether the city has an overall affordable housing mandate in the case of Molbak’s is likely irrelevant.

The yet-to-be-determined interim requirements are anticipated to stay in place until later this year, when the city expects a more thorough analysis on the impact of an affordability requirement in the context of Woodinville’s housing market. For now, the city is shooting from the hip with the 10% number. Allowing developers to utilize an existing state incentive program in which they receive a property tax break for providing the affordable units, via the state multifamily tax exemption (MFTE) program, is seen as providing an incentive to offset the mandate.

“This was a compromise to tell our city and tell our constituents and tell the property owners that we are serious about affordable housing, and we don’t believe that stopping construction citywide gets affordable housing,” Woodinville Mayor Mike Millman said of the pivot toward interim zoning in a conversation with The Urbanist. “We are going to get, I believe, to some type of mix of a carrot and a stick approach, like you want to develop here, here’s the mandatory [requirement], and if you want to take advantage of the MFTE benefit, we can do that.”

During the council’s discussion last week, Best-Campbell, who made the original motion on March 18 to consider a moratorium, brought up the idea that an initial 10% number could be too low.

“What concerns me most is: how low are we going to go in the interim? Are we going to go too low, that we give away a lot and don’t get much in return, all because we’re not willing to wait for what’s coming in the fall,” Best-Campbell said. “If we’re going to do something minimal? Okay, fine, let’s do something minimal. What matters to me is that we get something down that actually works, that gets some affordability started.”

Cities around the region that have implemented affordability mandates — also known as inclusionary zoning programs — have generally done so at the same time that they’ve created significant housing capacity through upzones. And most jurisdictions spend a considerable amount of time trying to calibrate its requirements. Redmond, which was cited in Woodinville as a positive example, has seen some success with its 10% mandate, but decided to increase that mandate to 12.5% in its key Overlake growth center last year at the same time that it added more housing capacity, including some highrise zoning.

Woodinville did not start to seriously explore implementing an affordable housing mandate until late into the process for updating its Comprehensive Plan, which has still not been fully adopted by the city council. With the council throwing out a number of 10 units as a minimum to trigger the requirement, it doesn’t look like any actual projects on the horizon are set to fall under that requirement, illustrating the fact that the move is more about signaling support for affordable housing rather than actually creating any.

“As far as any new projects over 10 units, there is nothing [that’s] currently been proposed,” Woodinville’s Development Services Director Robert Grumbach said at the meeting. “You do have discussions about the Green Partners project, but they’re still in the very early stages. Building permits for that aren’t going to be here, probably, for quite a while still.”

As cities regionwide grapple with an anticipated development downturn as high interest rates converge with new tariffs on construction materials, Woodinville is poised to quickly implement a new barrier that risks being the nail in the coffin, stopping homebuilding dead in its tracks as projects fail to pencil out as financially feasible.

“Let’s come up with a good number that we can be happy with, because I don’t want to just give things away to developers,” Best-Campbell said.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.