Will Issaquah’s light rail station become a parking crater or the heart of a walkable neighborhood?

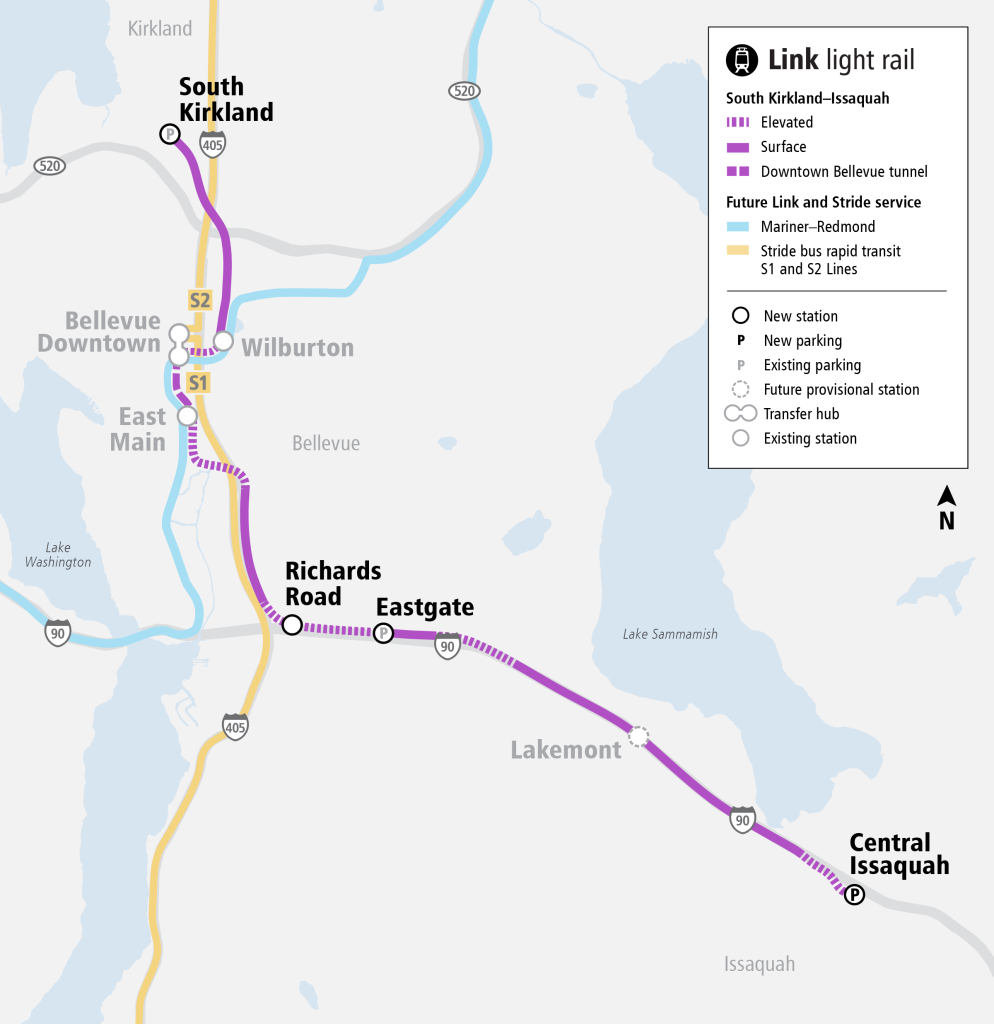

The idea of taking a light rail train to Issaquah seems like a far-off dream at this point, with service not set to start until sometime between 2041 and 2044. Nonetheless, the City of Issaquah is getting an early start on planning for its only light rail station, which is set to be the final stop on a future line that will add four stations and connect to three existing stations in Bellevue.

The South Kirkland-Issaquah Link is expected to see relatively modest ridership compared to planned lines to Ballard, Everett, and Tacoma, but it will represent a big change for Issaquah, with the area around a future station expected to accommodate significant housing growth in coming years. Estimated to cost nearly $2 billion, the 12-mile line would attract 12,000 to 15,000 daily boardings based on modeling Sound Transit conducted in 2020.

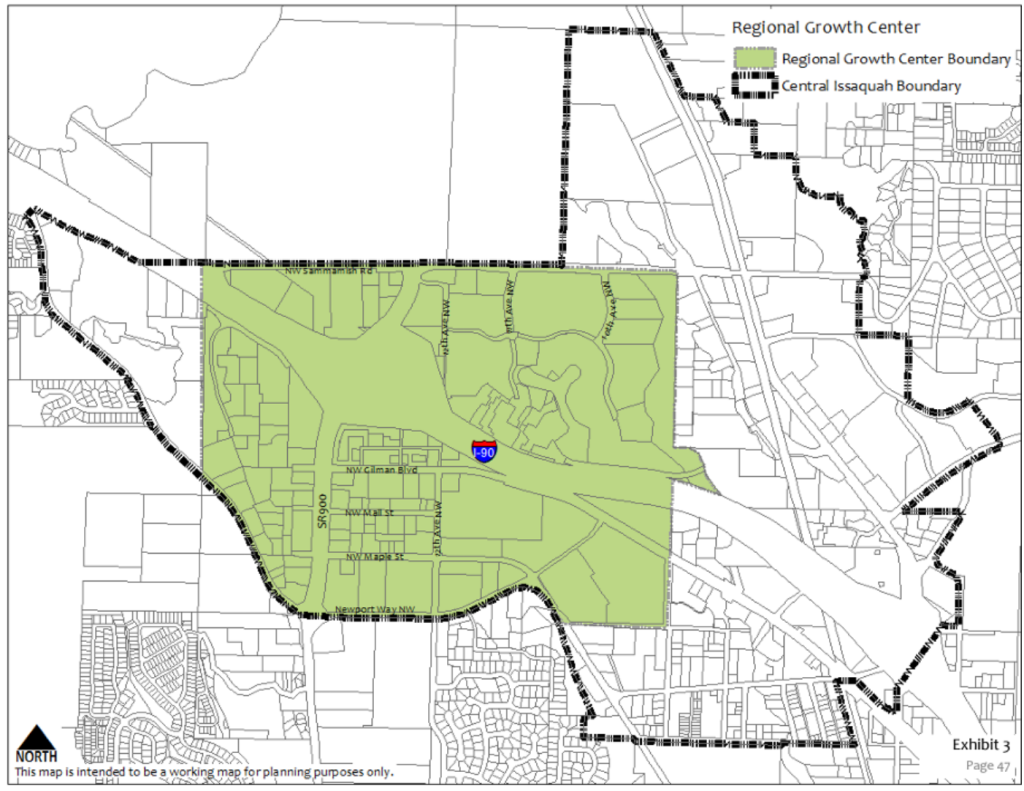

While the city has seen a fair amount of population growth in recent decades, most of that has occurred on the city’s periphery. Though Issaquah has been pursuing plans for infill development in Central Issaquah for years, it may take a catalyst like light rail to finally make it happen.

This week, the Issaquah Council unanimously adopted an official vision for light rail in the city and principles to guide that vision, building on a light rail planning guide the City adopted in 2024. The process to hash out that guide brought to light some competing interests that will duel for control of the city’s vision over the coming years. Together, this early work is intended to smooth the process as light rail planning starts to ramp up.

“This really creates the framework that we’ll need to evaluate future decisions, things such as station location, the track alignment needed for that station location, and then future action items such as land use and zoning to support that station area,” City of Issaquah transportation planner Thomas Valdriz told the council. “Sound Transit will be using this just as a starting point so they know what our aspirations are and so they can identify projects that are going to meet local needs as well as regional needs.”

At the heart of the conversation is: how much can Issaquah assert its priorities with an independent transit agency like Sound Transit? And when push comes to shove, with how will those priorities impact transit riders and the broader region?

The vision statement approved Monday, generic on its surface, draws a line in the sand around encouraging the area around a future light rail station to be walkable and well-developed. “By 2044, the Central Issaquah station area will be a vibrant, well-connected hub where people of all ages and abilities can easily live, work, and thrive,” it states. “Designed for walkability and sustainability, it will offer eco friendly transportation, diverse housing and businesses, and safe, welcoming, and inclusive public spaces.”

Looking at other regional models

More than just a broad vision statement, the guiding principles utilize several regional models for how Issaquah might approach its own planning, some more promising than others.

Transit-oriented development (TOD) advocates have cited Redmond as an example of a city that is focusing its main downtown station on amenities rather than parking, with satellite park-and-rides at Marymoor Village and Redmond Technology stations providing alternative parking options.

“By distributing parking across multiple locations, Redmond balances commuter needs with TOD priorities, ensuring land near stations is used for high-density, mixed-use development instead of large parking lots,” the guiding principles document notes. “Issaquah can adopt a similar strategy by leveraging nearby existing and planned park-and-ride facilities to serve commuters while preserving valuable land near the future Central Issaquah Station for TOD.”

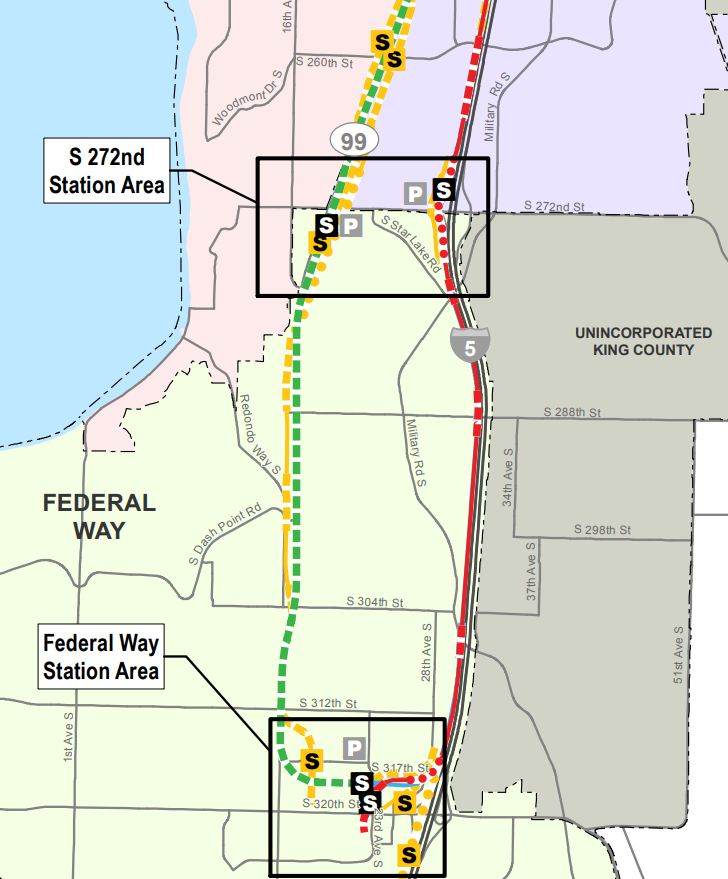

Other examples that Issaquah is turning to are less than ideal. Federal Way, which will see light rail service begin in 2026, is touted as a positive example of a city that shaped Sound Transit decision-making around its own city goals.

“[Federal Way] collaborated with Sound Transit to shift the light rail alignment from SR-99 to I-5, preventing redundancy with King County Metro’s RapidRide A Line,” the document states. “This adjustment minimized disruptions to existing transit services while preserving the city’s vision for the SR-99 corridor. Federal Way’s approach highlights how early and consistent advocacy, backed by clear zoning regulations, can help guide Sound Transit’s project to better align with local priorities.”

The decision to route Federal Way Link via I-5 instead of SR 99 is widely regarded by transit advocates as a major mistake. Light rail would never be redundant with A Line bus service, which terminates in Tukwila rather than heading to Seattle. Plus, the final alignment that was chosen ultimately reinforced parking-oriented stations like the one at S 272nd Street in Kent, which is paired with a 1,100-stall parking garage. In the end, concerns about impacts to existing properties along SR 99 won out over transit rider experience and the potential to add dense housing near stations.

While this is simply cited as an example, it illustrates how station placement discussions can ultimately end up throwing riders under the bus. More than trying to copy a specific outcome, Issaquah clearly sees its regional peers as a model to follow in terms of trying to push for its interests with Sound Transit.

“Sound Transit will be making final decisions, but we do have some pretty significant tools that can help us really steer the conversation,” Valdriz told the council in mid-March. “Specifically, we’re looking at zoning and land use as well as permitting. And so when we talk about zoning and land use, we’re really talking about ways that we can support transit operations from a densities of jobs and housing perspective, as well as the amenities that are going to support a successful light rail station.”

Pushing back on a major parking garage at Issaquah Station

The Issaquah light rail station, as the furthest east station currently planned on any Sound Transit vision map, will ultimately prove to be a draw for riders trying to access the system from further east in King County: cities like Sammamish, North Bend, Snoqualmie, and Black Diamond. During the process of adopting the guiding principles, the issue of how Issaquah will be ready to handle questions around designing for those users came up multiple times.

It’s clear that many Issaquah councilmembers aren’t wild about building a large parking garage next to their new station, encouraging users to drive to it. One lawmaker cited the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) as one system that is too car-oriented.

“If the vision is that Sound Transit is going to serve those folks with busses, then the station would need to have a larger number of bus bays, right?” Issaquah Councilmember Tola Marts said last month. “If the vision is — and you know where my concern comes from, right, it’s MARTA and the 2000-stall parking garages that are at the end of every single MARTA line, right? So if we have a vision for how we believe this station — we have to talk about how the station will work within Sound Transit as a whole, not merely for what we hope to get out of the station [as a city].”

Marts doesn’t need to look to Atlanta for light rail stations that have prioritized parking access over fostering a walkable neighborhood. Sound Transit has received significant criticism for prioritizing parking access at stations, which adds a large price tag to stations for a relative minority of riders. A 2021 financial reset did significantly delay a number of planned parking structures to decrease costs, in a clear illustration of their expendability, but the full ST3 build out still includes thousands of new parking stalls.

In the end, these guiding principles clearly represent an attempt to pivot away from Issaquah’s station becoming a park-and-ride. It recommends leveraging a distributed parking strategy: “This approach preserves valuable station-adjacent land for housing, businesses, and public spaces, supporting a walkable, transit-oriented environment while still accommodating regional commuters.”

Issaquah’s early principles focus instead on last-mile connections for people who walk and bike. It also recommends Issaquah advocate for forward compatibility, not only for the light rail network but also for other local and intercity public transit options that may not exist yet.

While this is only the beginning of the conversation, the seeds have been planted when it comes to issues to watch over the next couple of decades.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.