Senate Bill 5595 would encourage “shared” people-oriented streets.

What is a street if not shared public space? A city street is one of the few instances of true and actual public space in the city, at least in theory: it is always open; there is no cost to enter. You do not need a reason to be in it, and it is meant to accommodate all types of presence and uses.

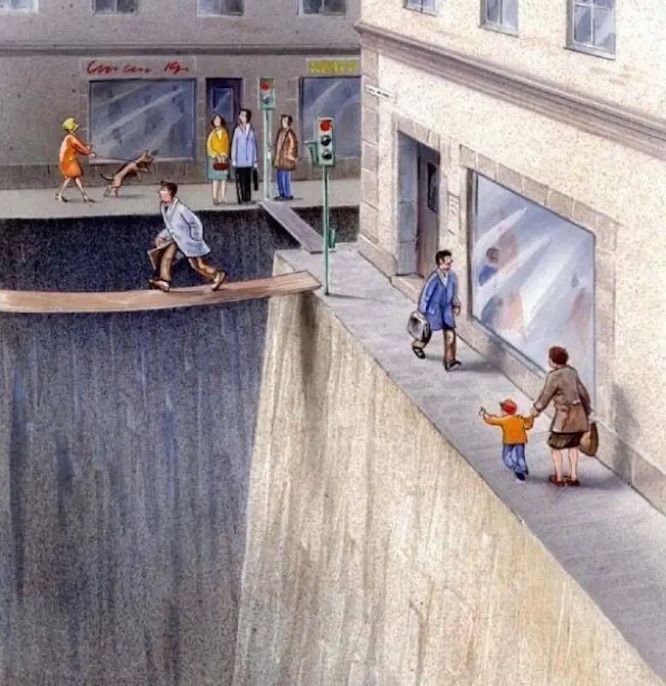

If your street or those you use daily do not feel that way to you, it is because we have designed and programmed our streets to operate as a monoculture: hospitable to cars first and foremost, and merely tolerant of everyone else.

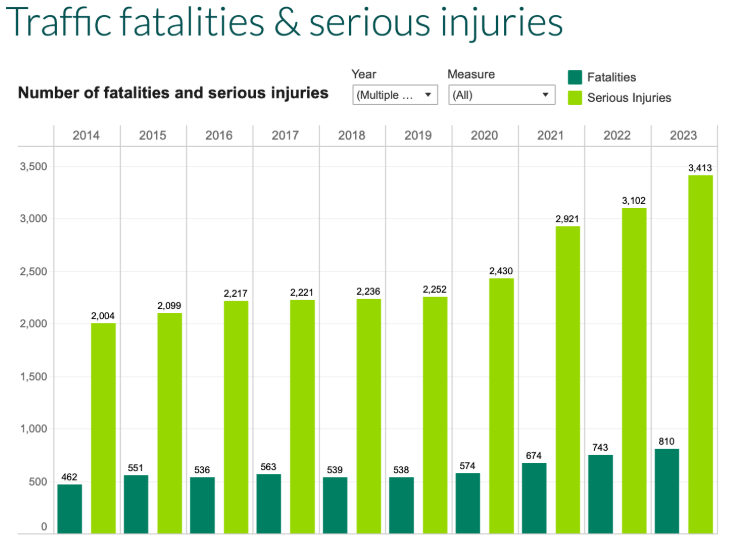

How safe and welcome do you feel on your streets? Anecdotal and empirical evidence indicates that the majority of U.S. residents do not feel safe or welcome on our streets — and that isn’t just people who walk or bike. U.S. roads are twice as deadly as roads in other parts of the world, and that’s saying something given our high engineering standards. Washington State has seen increases in road violence and death involving cars.

This is the cost of designing our public easements to privilege cars above people. A new piece of legislation, SB 5595, could — above its stated intentions — help us rethink and reclaim the street as a true public easement. If passed and its provisions delivered, we can look forward to streets that are not only more welcoming of public life, but a lot less deadly.

SB 5595, Establishing shared streets, allows “a local authority” to designate “any nonarterial highway that is not a state highway to be a ‘shared street,’” a designation that allows for vehicular traffic that does not exceed 10 miles per hour and where pedestrians, bicyclists, and people using micromobility devices (referring to motorized and non-motorized scooters, and motorized chairs).

I have been thinking about streets and the role these are allowed to play in our cities in light of the lessons we learned (or didn’t, maybe) during the pandemic. The pandemic offered a glimpse of what our streets could be — if we really unlock their potential. Seattle, like many cities, established an “open streets” program, wherein neighbors could use their streets for safe gathering, child’s play, jogging and walking, and more. Tacoma, like many cities, established a program through which businesses could occupy sidewalks and parking spaces for outdoor seating.

We also see how useful our streets could be during festivals and block parties. More than parks, plazas, and other designated recreational spaces, our streets are the most abundant instance of public space. It’s too bad so few of us get to use them fully but for a few select times each year.

SB 5595 states that a local authority can designate a street a “shared” street by placing traffic control devices “where pedestrians, bicyclists, and vehicular traffic share a portion or all of the same street.” Again, in my mind a street is a street only by virtue of pedestrians, cyclists, and vehicular traffic sharing a portion or all of the same street.” A roadway that restricts all but vehicles from the roadway is a tollway or a highway.

Because the street encompasses, technically speaking, sidewalks, planting strips, curbs, gutters, street furniture, utility poles, the utilities running below ground — and, yes — the roadway. It seems that the authors of this bill mean “roadway” when they write street.

While SB 5595 does remind us that our streets can be more — more public, more optimally used, more safe, and more open — this proposed legislation sends a mixed signal in the sense that all streets are already shared. We do not need to pass a law to establish this reality. But proposing such a law is yet another reminder that our streets are failing us.

SB 5595 joins efforts such as road diets and complete streets in our continuing effort to reclaim our public space. The bill provides local governments with a legal mechanism through which to enforce the public easements so few of us get to actually experience in our streets.

We do not experience streets as true public easements because automobile companies and auto enthusiasts have lobbied for restricting streets to automobiles only, arguing that streets are for cars and that anyone else who would think of using a street is a “jay,” an idiot. And that’s what it feels like to be a pedestrian on our streets today, does it not?

Their efforts have transformed our sense of what a street is, and the physical shape of streets themselves.

Through 2024, the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD)—a huge tome that establishes the look, feel, and function of all streets in the U.S. — encoded prescribed designs that make it unsafe for anyone not in a car to be in a street. A recent update moves state and other agencies towards the recognition that streets are sometimes used by people not in cars, and that more can be done to design streets so that these persons aren’t injured or killed by people in cars.

This is a small but significant shift. But it is not enough; for now, the MUTCD and the engineers who rely on it to design streets seem to assume that a street is only a street if it has a car in it. SB 5595 reminds us that it could be otherwise. More needs to be done to change our sense that streets can accommodate and support public life without putting people at risk of death or violence.

It’s way past time for things to be different. We need more public space — and we need it not to be dangerous. For a street to be experienced as a truly shared public space cars must be subordinated to other public uses. SB 5595 provides for that not through the exclusion of cars (though some streets could exclude them and still be a street), but by stipulating that vehicles be operated at low (people-friendly) speeds—10 miles per hour.

SB 5595 could be the start of a reformation of our thinking regarding the public realm and its potential. It may be the start of a process through which we retake more of our most precious public space, the street.

When I think of a shared street I think of State Street in Madison, Wisconsin. Here is an eight-block-long street connecting the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus to the Wisconsin State Capitol. The street does not wholly exclude vehicles — busses and delivery and service vehicles are allowed at low speeds. State Street is the city’s Main Street — and it actually functions as that. The shops, eateries, bars, and other businesses that line State Street are always busy. Local businesses thrive here because people prefer to walk up and down State Street rather than other, car-ridden streets.

State Street in Madison is a strong opposing argument to all who say that not accommodating cars “kills business.” It is a strong argument for the value and potential of SB 5595.

(This even as SB 5595 calls for traffic control devices and annual reporting on “accidents” involving vehicles and DUIs, two requirements that may prevent “local authorities” from implementing shared streets as these encumber already scarce public resources; if anything, these requirements make their own case for why we so desperately needs shared streets that are actually shared as they speak to fear we have of private vehicles on public space).

If we are to use traffic-control devices to delineate the shared street that is actually shared then we have a model in London’s low-traffic neighborhoods (LTNs). LTNs are a solution to a problem leaders in London have been grappling with — one all too known to us in Puget Sound: road networks that are oversaturated with motor vehicles.

LTNs are, in practical terms, simple. Street planters or other “filters,” such as metal gates or even just monitoring cameras, are used to block traffic from using residential streets. They are strategically placed in order to keep the flow of cars on main roads and away from people’s homes, where noise and air pollution can have a serious impact.

Peter Yeung – Reasons To Be Cheerful

I observed such an LTN in another context, Córdova, Spain, where local neighborhoods used bollards to prevent non-local traffic from entering neighborhoods. Within the neighborhood vehicles were kept to low speeds by other design features (not only through aspirational measures such as posted speed limits) such as planters and street trees. If these streets were inaccessible to most private vehicles, they were fully accessible to people on foot or bike, and the experience of being on these streets was safe and comfortable.

If the pandemic taught us anything about public space it is that we need it and that we don’t have access to enough of it. It’s there; most of us just can’t use it fully. And the most abundant instance of public space is uncomfortable to be in (at best) or deadly (at worse) for most.

If the pandemic taught us something else about public space is that it does not take much to realize the street’s potential.

I would argue that we need neither traffic control devices nor a new law to use our streets as they are meant to be used (we were able to do it during the pandemic, and societies outside of the U.S. have been leveraging streets in more life-sustaining ways for a lot longer than the U.S. has been an urban nation). Still, there is utility in this bill in that it helps remind us that our streets can be more than a monoculture. Also, it gives traffic engineers an incentive to rethink the street and, in time, to design streets that are actually shared.

Just as we are learning that monoculture is an unsustainable way to grow our food, we are learning that monoculture on our streets is an unsustainable way to design and program our streets. Our streets are capable of sustaining more than a single use — vehicle circulation — they can be a place for public life in everyday living.

SB 5595 may begin with an incomplete sense of what streets are, but its true value lies in reminding us of their potential and in how it provides cities in Washington with a legal avenue through which to reclaim our abundant public space for people.

To stay alive, SB 5595 must advance out of the state House before the opposite house cutoff on April 16. It’s scheduled for executive session in the House’s Transportation Committee this afternoon. Comment on the bill on the legislation page.

Rubén Casas

Rubén joined The Urbanist's board in 2022. He is a scholar and teacher of rhetoric and writing at the University of Washington Tacoma. He is also the faculty lead of the Urban Environmental Justice Initiative at Urban@UW. In his work and advocacy, Rubén examines how cities and the institutions that comprise them imagine, plan, and build in ways that promote and/or discourage community and a sense of place.