A housing bill clearing the way for more accessible buildings and lower building costs via elevator reform jolted to a sudden stop this week at the Washington State Legislature. Senate Bill 5156 died in the House Housing Committee after a key deadline passed Wednesday without a vote, despite a landslide 42-6 vote by the state Senate on February 19.

Sponsored by Senator Jesse Salomon (D-32nd, Shoreline), the bill would have required the state to allow smaller, lower-cost elevators that meet global standards, in contrast with the more circumscribed requirements in place in the U.S. and Canada.

Current state regulations require new elevators to be large enough to handle a full-sized ambulance stretcher in case of emergencies, a requirement that drives up elevator costs and leads to an absence of elevators in many newly constructed lowrise buildings and fewer elevators than could be possible in larger apartment buildings.

SB 5156 was intended to expand the number of accessible units, which often end up being constructed only on the ground floor of many buildings. The bill would have required that the state allow elevators that are just large enough to accommodate a wheelchair user, in buildings with up to six stories and with fewer than 24 units.

Opposition to the bill primarily came from firefighter advocacy organizations, which have stated concerns about reducing the size of elevator cabs, and from the state’s elevator constructor’s union, which benefits from the status quo when it comes to North American elevator standards. Those standards help reinforce a tight monopoly on elevator production, keeping the high-demand elevator labor market small.

In testimony before the Housing Committee last month, a representative for the International Union of Elevator Constructors (IUEC) Local 19 also presented their main argument against the bill as safety-related.

“While we understand the legislature is grappling with the important goal of increasing affordable housing units, this bill proposes to do so by skirting important safety requirements related to elevators, specifically that global safety standard, also known as ISO,” Lindsay LaBrosse, business representative for IUEC Local 19, told the committee. “This includes removing safety requirements that allow first responders to evacuate tenants quickly during an emergency like a building fire, as well as ensure that no one is burning alive inside of an elevator.”

However, reform proponents point to statistics indicating that apartment buildings with modest elevators (or no elevators at all) are at no greater risk of fire deaths or other disasters compared to those with America’s supersized elevators. This point was underscored in a Center for Building in North America deep dive report by the group’s executive director, Stephen Smith, which analyzed why elevators in the US and Canada are so expensive relative to international peers.

“Fundamentally, the claim is that elevators everywhere else in the world are unsafe,” Smith told The Urbanist. “You’ve got to make a really wide-ranging accusation of unsafety in basically the entire world in order to buy this.”

Smith pointed to the unique arrangement in place between North American elevator manufacturers and the elevator constructor unions as being a major driver behind high elevator costs compared to the rest of the world.

“Elevators are very expensive in the United States, and as with a lot of things, labor is a major component of the expense, and the elevator union has negotiated some agreements with its employers, the manufacturers, which create a lot of work,” Smith said. “This does not exist in other countries. It takes about twice as long to install an elevator in the United States as it does in Western Europe.”

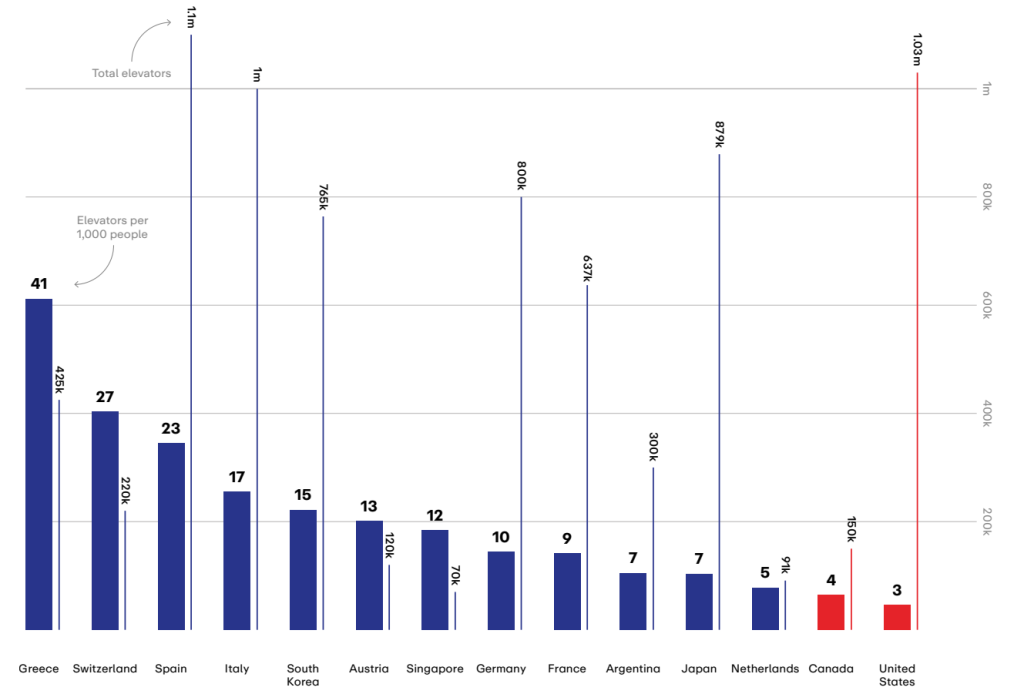

Smith’s report detailed how the US has one of the lowest rates of elevators per capita compared to other high-income countries, with Spain currently having more than seven times the number of elevators in the US after adjusting for population, and Greece having more than 13 times what the U.S. does. It notes that Spain has fewer than half of the number of multifamily buildings than the U.S. does, yet the two countries have roughly the same number of elevators in absolute terms.

This is the first year that the idea of elevator reform has been floated in the Washington legislature, but it is clear that push back from the elevator constructor’s union played a role in halting the bill’s momentum after it sailed through the Senate.

“It’s a relatively new idea, especially for our committee,” Rep. Strom Peterson (D-21st, Lynnwood), chair of the House Housing Committee, told The Urbanist. “There was certainly some opposition from firefighters, from the labor unions that put in elevators. And, to me, it was getting a lot of attention. I think the idea is relatively sound, but I didn’t see it as emergent as some of the other issues we’re dealing with. I think we can do some work in the interim. We can get something done in the next year or two, and it’s really not going to have a big impact on projects.”

Peterson cited another bill, the Parking Reform and Modernization Act, as one that would potentially have a bigger impact compared to elevator reform. That bill was modified in another House committee last month to add long implementation timelines that could reduce its immediate impact.

“Energy, I felt, was being expended on a bill that wasn’t going to have a huge impact and probably still needed a little bit of work,” Peterson said.

Housing advocates aren’t fully in agreement with Peterson that there won’t be a big impact from halting the bill.

“It’s incredibly disappointing to see that the elevator bill — specifically written for more affordable elevators in taller single-stair buildings — has been shelved. We have a crisis of care in this country, and an aging population. Anyone can find themselves in need of accessible or adaptable housing at some point in their life,” Mike Eliason, architect and founder of the housing thinktank Larch Lab, told The Urbanist this week.

An advocate for legalizing single-stair buildings, Eliason contends these “point-access blocks” will maximize livable space in buildings while reducing housing costs and making the most of small urban infill lots. Builders seeking to construct smaller apartment buildings struggle to make expensive supersized elevators work with their design, but would be far more likely to squeeze in a smaller elevator.

At 63' tall, Seattle's DP Studios is a slender mid-rise providing 22 units on a small 3,200sf site. Designed by ECCO Design & Architecture, the infill point access block would illegal to build in most US cities due to its six story height and single egress stair.

— Sean Jursnick (@seanjurs.bsky.social) November 9, 2024 at 5:16 PM

[image or embed]

Eliason, who has regularly contributed articles to The Urbanist, argued that other statewide building reforms won’t see their full potential realized without reforms like SB 5156, particularly the 2023 middle housing law, HB 1110.

“We will see tens of thousands of homes developed under HB 1110 – but the vast majority of them will not be accessible, visitable, or adaptable,” Eliason said. “Significantly more affordable elevators would lead to more installations – meaning more jobs, more accessible homes, more affordable homes, and more climate adaptive homes.”

Elevator reform will almost certainly be back in some form at the legislature as soon as next year, and ultimately legislators will be faced with a choice over whether to continue the status quo, or to challenge the powerful elevator union lobby and push for change.

“This is a plain tradeoff between having an elevator that can fit a stretcher, and not having one at all,” Smith said. “As you start to allow more single-stair buildings there’s going to be fewer units that each elevator is serving. And as a result, these really expensive elevators are going to make developers think twice about including an elevator, and they already have.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.