Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell has failed when it comes to addressing housing costs and planning for the next generation of Seattleites. Whether kickstarting a homegrown social housing push, encouraging a wide diversity of market-rate housing, or scaling up traditional nonprofit low-income housing to meet the need, Harrell’s halfhearted efforts have fallen flat.

As he faces a reelection fight in the fall, voters should ask what Harrell has accomplished in the last four years, and why we would expect any better in the next four if he wins.

Harrell has failed to lead on the key issues facing the city. When he ran for Mayor, Seattle voters’ top concerns were homelessness, housing costs, and public safety issues, including crime and drugs. Today, they still top the list, a telling sign of too little progress on those issues.

In the first part of this series, I covered Harrell’s miserable failures to address public safety: Violent crime was getting better before he started, here and nationally, and it only got worse and diverged from the rest of the county after he became Mayor. In fact, it is still much higher than when he took office. He cut funding for drug treatment and failed to effectively address the fentanyl crisis, presided over a series of scandals at the police department, and lit $100 million on fire to grow the police department by one officer.

Today, I turn to Harrell’s failure to address housing costs.

Buyer beware

First, let’s look at outcomes for people buying homes. With a 20% down payment, the median monthly mortgage payment for a Seattle home right before Harrell took the helm was $2,935, against a median monthly income of $9,167. That mortgage would eat up 32% of monthly income, to say nothing of property taxes and homeowners insurance.

Today, the payment for the median home is $4,512 out of a monthly median household income of $10,005 — a ghastly 45%. Throw in taxes and insurance and our median income earners would be on the edge of what the federal government defines as “extremely cost burdened.” Yikes.

On the surface, this is due to interest rates, which are beyond his control. But Harrell could have taken significant steps early on to increase the number of homes that hit the market. Housing prices would have adjusted down somewhat in response to the added capacity and cost pressure from higher mortgage rates. But Harrell did not, so prices remained stubbornly high.

This isn’t theoretical. Austin, Texas aggressively ramped up supply and its home prices have been decreasing since 2022, despite its status as a destination for tech workers.

Rent burden

The rental story is more optimistic than home purchases, but a closer look suggests Harrell deserves little credit for that fact.

Median rent has moved much more modestly, from $1,845 a month to $1,891. In fact, it has fallen a teensy, tiny bit from 20% share of median income, to 19%. Now, renters’ paychecks are smaller than homeowners’. But this “median” number does give a sense of rental purchasing power, and lower income families have actually had higher wage growth than others. So we can safely say that rental purchasing power is at least holding steady. (That may not be people’s personal experience, however, with other household expenses increasing so quickly).

Given that we are in a cost of living crisis, I wouldn’t call holding steady great, though. As I mentioned before, Austin has allowed itself to build enough homes that people aren’t stuck bidding on the few open places to live that are left over. Just like home purchase prices, rental prices have dropped significantly in Austin. It has fallen from 13% from $1,614 to $1,398.

Set against a backdrop of income increases – their residents’ buying power for housing is increasing sharply. Seattle’s is most certainly not.

Housing growth outcomes

Harrell comes out looking even worse if you look more closely at the data. In general, a mayor’s main way to address private market home prices is make it easier to build. Mayors cannot affect the cost of lumber, labor, or borrowing money. But if they ease the path to building more homes, more homes do get built than would otherwise, and people are less likely to have to fight over a few scraps of available homes in the market.

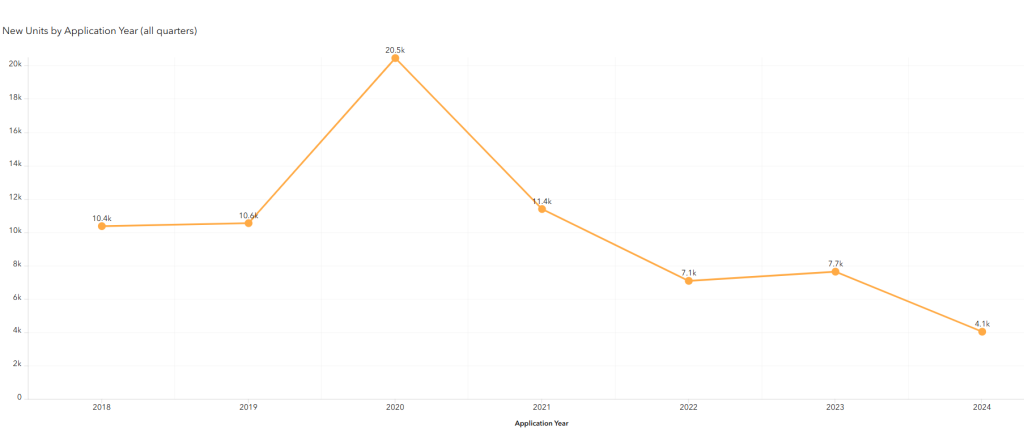

Measuring this is tricky because new homes are a bit of a lagging indicator. For instance, Seattle saw a surge in permit applications in 2020, in part due to temporary measures during the pandemic that made permitting easier, a program Harrell failed to make permanent. That surge shows up as a bunch of permits in 2021. All this was pre-Harrell. Those units were finally completed during the last few years, during his administration, but it would be tough to give him credit since they were permitted before he even started. The permitting boom just so happened to occur while Harrell was on a two-year break from elected office, after 12 years as a councilmember when Seattle’s housing crisis was exploding.

Most homes added over the last four years were apartments, which helps explain why rental prices are flat and we have a vertiginous increase in the cost of home ownership.

But all of this was baked in before Harrell. We have seen a rapid decline in permitting after he took the job. One big driver of the downturn is interest rates, of course – but Harrell has done very little to help.

Affordable housing

When it comes to subsidized affordable housing for people earning between 30% and 80% of the local median income, Harrell also has a poor record. He started off okay, supporting a renewed housing levy that increased spending significantly, although was likely to deliver the same amount of housing as the last one.

But Harrell soon turned around and de-funded other affordable housing sources. He has cut $20 million in annual spending on affordable housing from the general fund. And then he took payroll tax revenue that was largely dedicated to affordable housing and rewrote the law so he could take $81.5 million in planned annual spending away from affordable housing too. By the way, Seattle implemented its corporate payroll tax in 2020 right after Harrell left office after 12 years as a councilmember, but that hasn’t stopped him from monkeying with the spending plan as mayor.

Harrell also promised to build 2,000 units of shelter in 12 months. He didn’t. In fact, it’s been more than 39 months since he became Mayor and he still hasn’t, even if you include the shelter beds that are under construction.

Social housing

In 2023, Seattle voters passed an initiative that created a public development agency focused on building social housing. These would be mixed income, green, built by unionized labor, and permanently affordable. Once purchased, the higher income rents would help subsidize the lower income rents, making it less of a long-term drain on the public purse. Experience elsewhere has shown this can be quite successful.

The idea was popular and passed with a substantial margin, even as Harrell sat on the sidelines. But then the Mayor and the council did nothing to fund it.

So the grassroots activists who created the developer got an initiative on the ballot to fund it with a modest payroll tax of five cents on the dollar for individual annual earnings above $1 million–the first million is free each year.

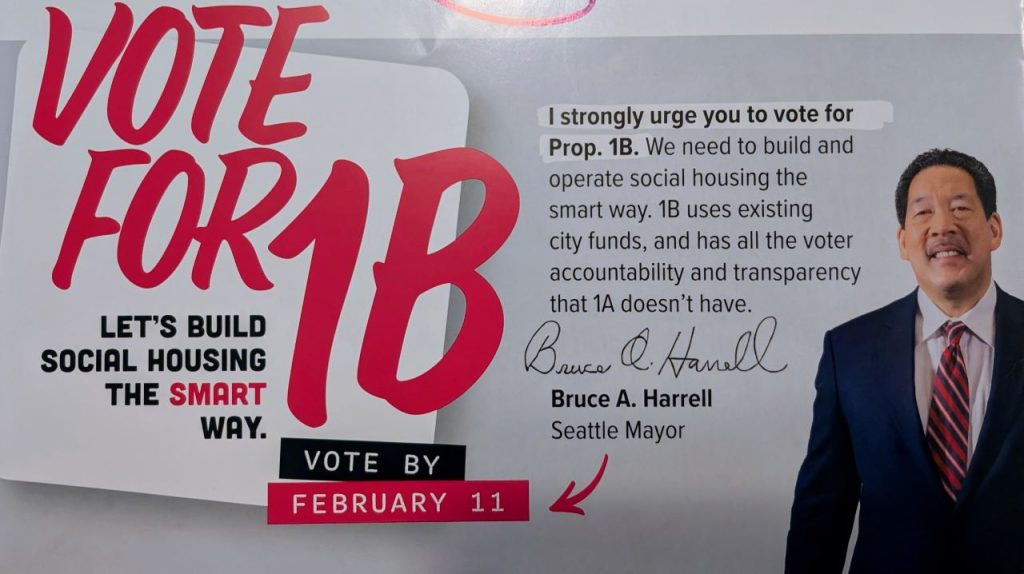

The corporate behemoths balked and the Mayor put his face all over mailers to try to stop this. The chamber colluded with the council to (likely illegally) force the measure onto a special February election ballot, when the electorate would be smaller and the Chamber’s big money would be more effective in defeating the measure.

Then they tried to bamboozle voters by putting an alternative on the ballot, a “funding” source that actually just took money from the kind of traditional affordable housing discussed in the previous section.

Bruce Harrell’s face was splashed across the opposition literature, which was paid for by Amazon and their Chamber cronies, right around the time Amazon had bribed the Trump family with $40 million. Unsurprisingly, Harrell and Amazon’s attempt to keep this middle class, affordable housing out of Seattle so that the richest corporations in the world could stay just a tiny bit richer flopped.

So, lucky us, we the people overruled him. But with a hostile Mayor in the office, there are serious threats to implementation – the fight for social housing is far from over.

As is the fight for housing of every type.

Harrell’s tepid 20-year plan for growth

Harrell hasn’t been much better when it comes to making it easier to build market-rate homes either.

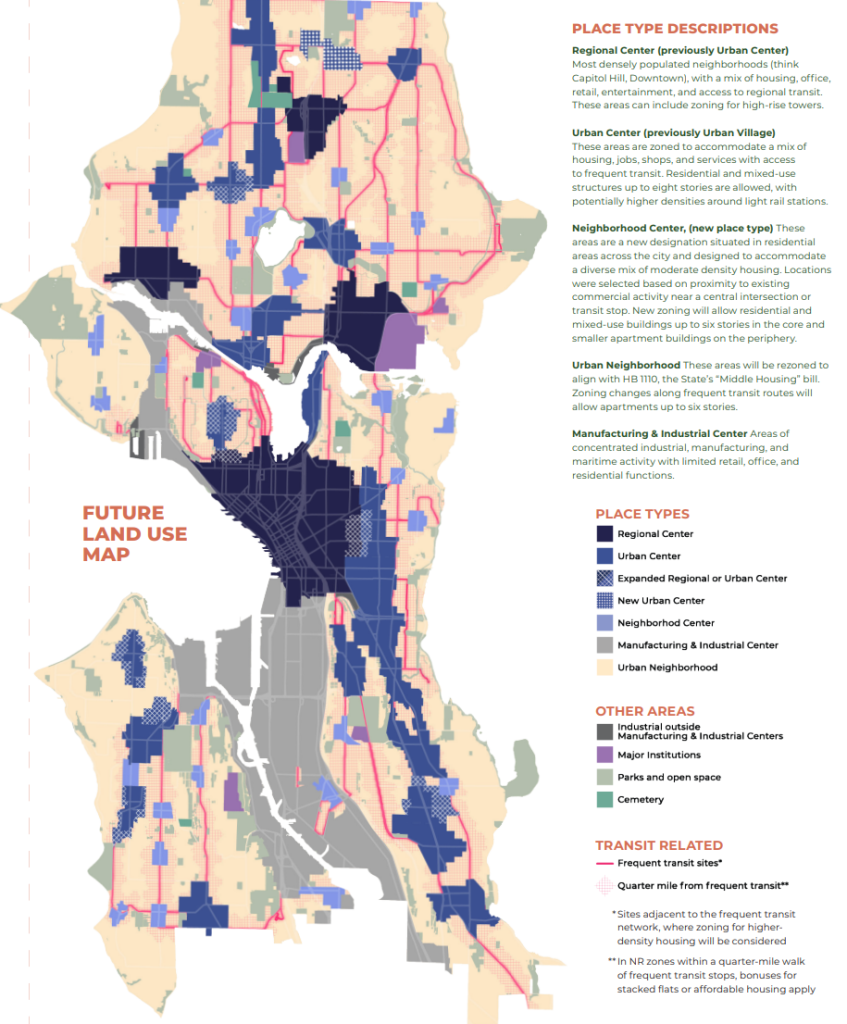

Our state-mandated 20-year plan for growth (officially called the “comprehensive plan”) is long past its due date, in significant part due to lackluster work, confusion, and infighting in the Harrell Administration. While after years of cajoling from the outside, it is approaching sort-of-okay, it is not good, and we only got this far because a broad spectrum of advocacy groups – from far left to MAGA friendly, have been dragging the Mayor slowly there. And now some of Harrell’s conservative council allies seem hellbent on making it worse.

One of Harrell’s early draft plans included five options for environmental review (a legal process that protects the plan from legal appeals over the coming years, which also makes it hard to change), and only one of them was even decent. Then the administration took public comments, and after overwhelming feedback that it needed to get more serious in round two, it didn’t. Cue another round of onerous outreach and presentation in neighborhoods and feedback, and people begging the Mayor to find a modicum of ambition within himself, and he released his big draft.

At the time, I characterized this version as Harrell throwing in the towel on housing. After years of work from so many people, his plan was to produce fewer housing units that we needed just to keep up. It was a plan to make things worse over 20 years – not tread water, not improve – but make things worse. In addition to failing to address the core problem of housing capacity, the plan doubles down on excluding new families from most Seattle neighborhoods, and forcing those that do come to live alongside busy, dangerous, polluted roads.

The mayor’s plan focuses on adding townhomes, which are not as affordable as stacked flats or condominiums typically are. Townhomes are oriented around stairs, which makes them inaccessible to people with disabilities and many seniors. They are also an inefficient use of scarce land in that much of their square footage is dedicated to stairs instead of living space.

It turns out too that Harrell’s planning department could not be blamed. They did not agree with him; in fact they gave him a more ambitious proposal. Harrell simply overruled them. He also ripped anti-displacement provisions out, cut back on apartments in rich neighborhoods, including his own, and was criticized by his own planning commission in public for his status quo approach.

The plan now faces more possible downsizing on council, with conservatives pushing for the zoning equivalent of a wall around certain wealthy neighborhoods. There is little indication that Harrell is doing anything to save what is left.

The lateness of the plan and legal appeals from anti-housing homeowner groups means that the City Council may need to resort to an interim ordinance in order to implement the state’s middle housing mandate before the required deadline at the end of June. Instead of fighting to keep his stacked flat bonus in the interim ordinance, it appears Council is planning to jettison it, sacrificing the opportunity for more affordable homes — at least until some future date when permanent legislation is hashed out.

Getting the growth plan passed ahead of the deadline, like most cities around the region managed to do — from Shoreline to Bellevue and Tacoma — would have meant a whole nother year to jumpstart housing production and give homebuilders another tool to add more abundant and affordable housing. But that was too much to ask for this feckless administration.

On housing affordability, as with public safety, this mayoralty is a failure. There are a few bright spots (social housing, modest improvements to the comprehensive plan), but those have come in spite of Mayor Harrell, not because of him. The biggest housing wins of the last two decades have come when Harrell wasn’t in office or because state leaders intervened, despite Harrell having 16 years to work on solutions.

Why would we expect the next four years to be different?

Ron Davis (Guest Contributor)

Ron Davis is an entrepreneur, policy wonk, political consultant, and past candidate for Seattle City Council. He is focused on making his community a place where anyone can start a career, raise a family, and age in place without breaking the bank. He has a JD from Harvard Law School and lives in Northeast Seattle with his wife — a family physician — and their two boys.