Boosting housing growth and tree canopy is possible with smart regulations.

It’s no secret that I love trees and housing. In 2018, I wrote an article for The Urbanist highlighting that livability in cities requires both density and abundant trees – and with the effects of climate change looming large, more urban housing and trees (and a whole lot less driving and sprawl) will become more imperative. That livability piece formed the foundation for my recent book on sustainable development, “Building For People,” highlighting all the ways we could be doing this (hint: ecodistricts and single-stair buildings).

I was quite horrified to realize the One Seattle Comprehensive Plan, the 20-year growth plan outlined by Mayor Bruce Harrell, prioritizes townhouses over trees, and it still heavily concentrates affordable housing along loud, dangerous, and toxic corridors and arterials. While the Comprehensive Plan may be put on hold as the Council considers interim legislation to comply with the state deadline in HB 1110, we must move the Council to fix these major deficiencies for the final Comprehensive Plan.

This could be our last chance for quite a while to make major changes so that at least parts of the city can adapt to our rapidly changing climate.

The Mayor’s Preferred Alternative for the Comprehensive Plan update eliminates nearly 20,000 apartments – including 3,500 affordable homes (MFTE + MHA) that would be produced with Alternative 5: Combined (Exhibit 1.6-15). The mayor’s alternative also results in the most demolitions of existing multifamily housing, which will drive up displacement and housing costs. The city, as it has for the past 30 years, continues to radically rezone areas that already have existing multifamily and commercial buildings, rather than boosting zoning more broadly.

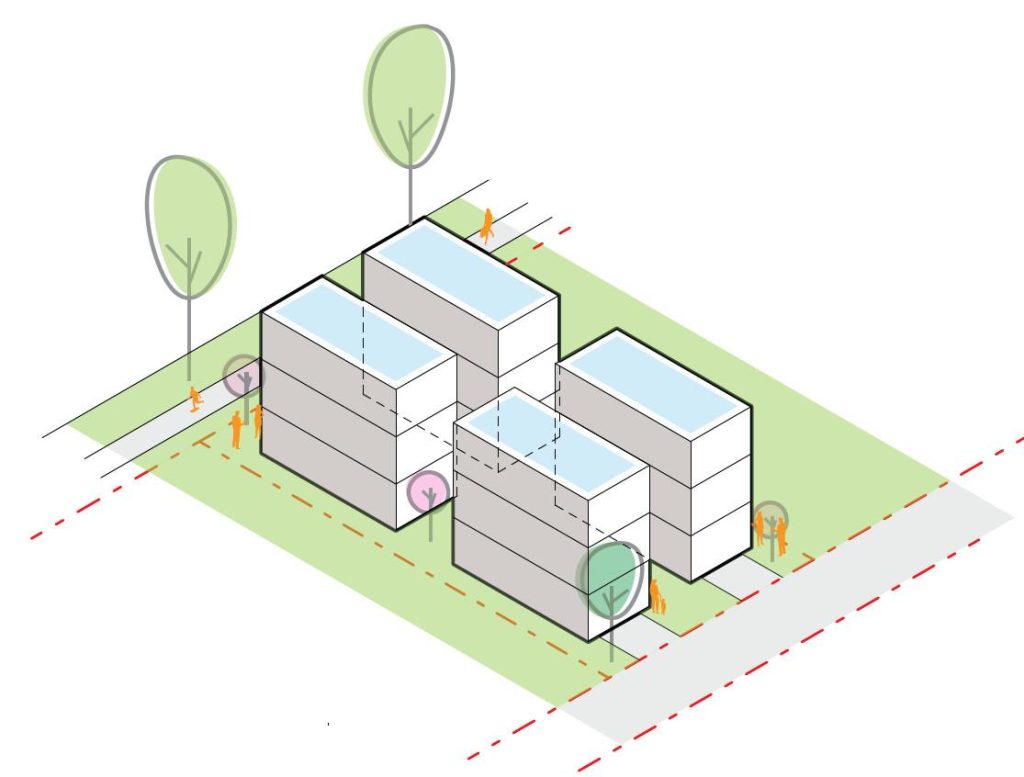

The 20,000 apartments that the Preferred Alternative jettisons are switched for ‘non-stacked flat’ housing in Neighborhood Residential zones (formerly single family zones). The redevelopment in these zones will largely only be three project types: four detached “tombstone” houses, townhomes oriented deep into the lot, or double duplex scenarios.

These sprawling developments will consume most of the lot, with driveways, walkways, and parking consuming much of the rest. There will be little space for trees and nature – and virtually none for community, for kids, or for climate adaptation. Plus, stair-heavy townhomes are inaccessible to people with disabilities and less friendly to aging in place.

Developers will build these project types because they are far easier than other options; they use the residential code instead of the building code (less difficulty and lower construction costs), have lower builder’s risk insurance, fewer or no sprinkler requirements, and no condo liability laws. This block in West Woodland gives a good sense of the sorts of project types and lot coverage we will see in Neighborhood Residential zones under the proposed legislation.

It doesn’t have to be this way. We can prioritize more homes and trees and space for residents. This is a block in Germany, with relatively strict regulations on where buildings can go, but flexibility on what the building is. Thus, there are small apartment buildings next to attached houses, next to rowhouses, next to affordable non-market housing such as cooperatives and baugruppen.

The difference in tree canopy could not be more stark. Notably, this effect is similar to dense neighborhoods in many European cities, where height becomes the toggle for increasing density (and yes, by and large with thin single stair buildings, instead of the thick double loaded corridors our codes induce in the U.S.).

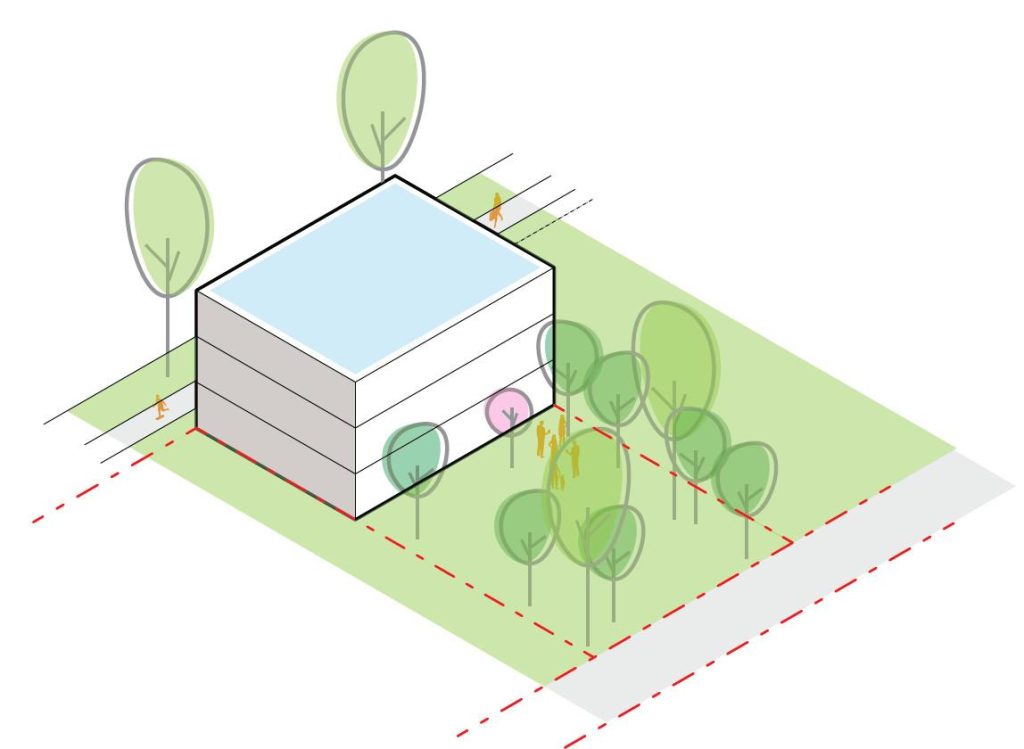

In short, European builders tend to build fairly tall buildings on a smaller portion of the lot than American urban builders , providing much more space for trees, green space, gardens, and so forth. Rather than rigid setbacks, an eco-friendly building often hugs a few of the lot lines with build-to lines which allows for better unit layouts, more contiguous space for trees, and the potential for a large garden to take shape.

Instead, in the U.S., we’ve mandated large set-backs on small lots, upper-level setbacks, and off-street parking and driveways that carve up much of the space where housing would go and trees could grow large. Instead of lush gardens and more privacy, Americans are left with copious asphalt, sad little planter strips, and less housing that is more expensive to build.

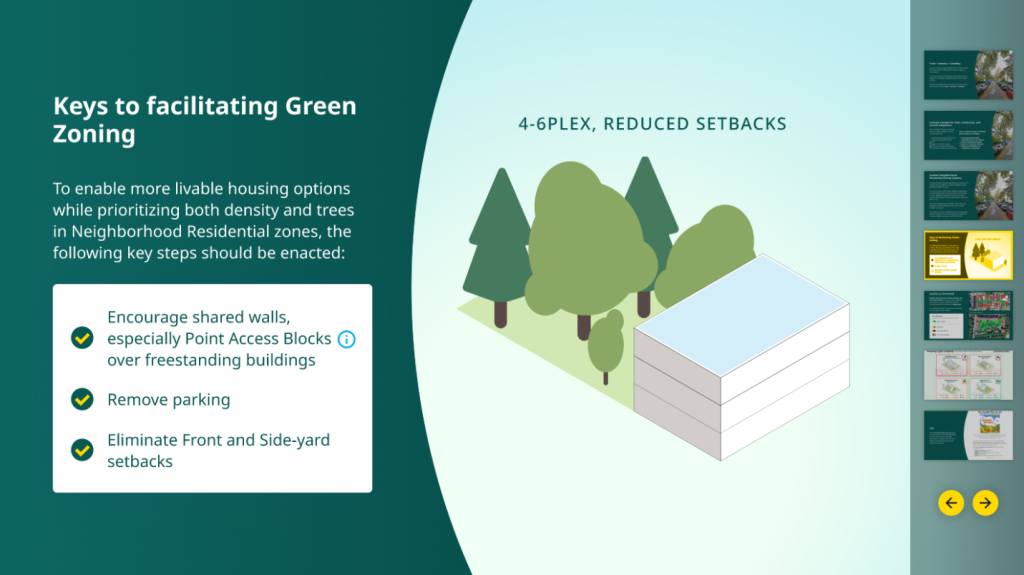

The following key moves would incentivize more affordable housing types in more compact development – allowing much more contiguous space for tree canopy and community:

- Eliminate parking minimums: Nationwide, vehicle miles traveled (VMT) ticked up again in 2024. Climate forward cities should be doing everything we can to reduce car ownership and VMT. There are 60% more cars in Seattle today versus 30 years ago – in that same timeframe, Paris has seen a 45% reduction in the number of cars. Eliminating parking requirements won’t prevent developers from adding parking – but will allow for more flexibility on marginal projects.

- Allow stacked flats on 5,000 square foot lots and raise the FAR bonus from 0.2 to 0.6, or more: Currently, the Neighborhood Residential Update includes a small bonus in buildable area, boosting the allowed floor area ratio (FAR) by 0.2 to incentivize stacked flats. Unfortunately, this bonus is far too small and should be tripled to overcome the inertia that prevents other options such as courtyard buildings, stacked flats, condos, and small multiplexes. Allowing these on 5,000 square foot lots will allow these types of buildings in more walkable neighborhoods, instead of car-dependent parts of the city.

- Lean into 3.5- and four-story single stair buildings: The city has allowed six-story single stair buildings for nearly 50 years, leading the country on this building type found the world over. The Washington State Legislature is currently working through SB 5156, a bill that would allow for more affordable elevators on single stair buildings up to six floors. Incentivizing stacked flats to go higher than three stories will lead to more affordable and more accessible homes.

- Eliminate side yard and front yard setbacks: The only way to prioritize abundant open space, contiguous open space for trees and housing is to eliminate side-yard setbacks. Side-yard setbacks place buildings sprawling deep into the lot and perpendicular to the street – with homes looking directly into adjacent lots. In the rest of the world, eliminating side-yard setbacks places the building parallel to the street – with homes looking over the street and backyard. It’s better for privacy, for embodied carbon, for energy efficiency, and for open space. The current 10-foot setback is far too large. Zero would be ideal, but the Japanese and Dutch work magic in just 18 inches.

To help the Council, planners, and residents better understand how all of these issues interact, I’ve teamed up with several friends to develop an educational website to better visualize the impacts of these recommendations.

Alternative 5: Combined is the only comprehensive plan alternative studied that maximizes both affordable housing and space for trees in more of the city. If Seattle leaders are serious about being a welcoming city, with more affordable homes and prioritizing climate and room for trees, then they must incentivize the construction of more compact buildings with smaller footprints, taller height limits, and shared walls. This is the status quo of nature-inclusive, walkable, and very livable cities and villages the world over, and it’s time Seattle leaders acknowledged this.

Mike is the founder of Larch Lab, an architecture and urbanism think and do tank focusing on prefabricated, decarbonized, climate-adaptive, low-energy urban buildings; sustainable mobility; livable ecodistricts. He is also a dad, writer, and researcher with a passion for passivhaus buildings, baugruppen, social housing, livable cities, and car-free streets. After living in Freiburg, Mike spent 15 years raising his family - nearly car-free, in Fremont. After a brief sojourn to study mass timber buildings in Bayern, he has returned to jumpstart a baugruppe movement and help build a more sustainable, equitable, and livable Seattle. Ohne autos.