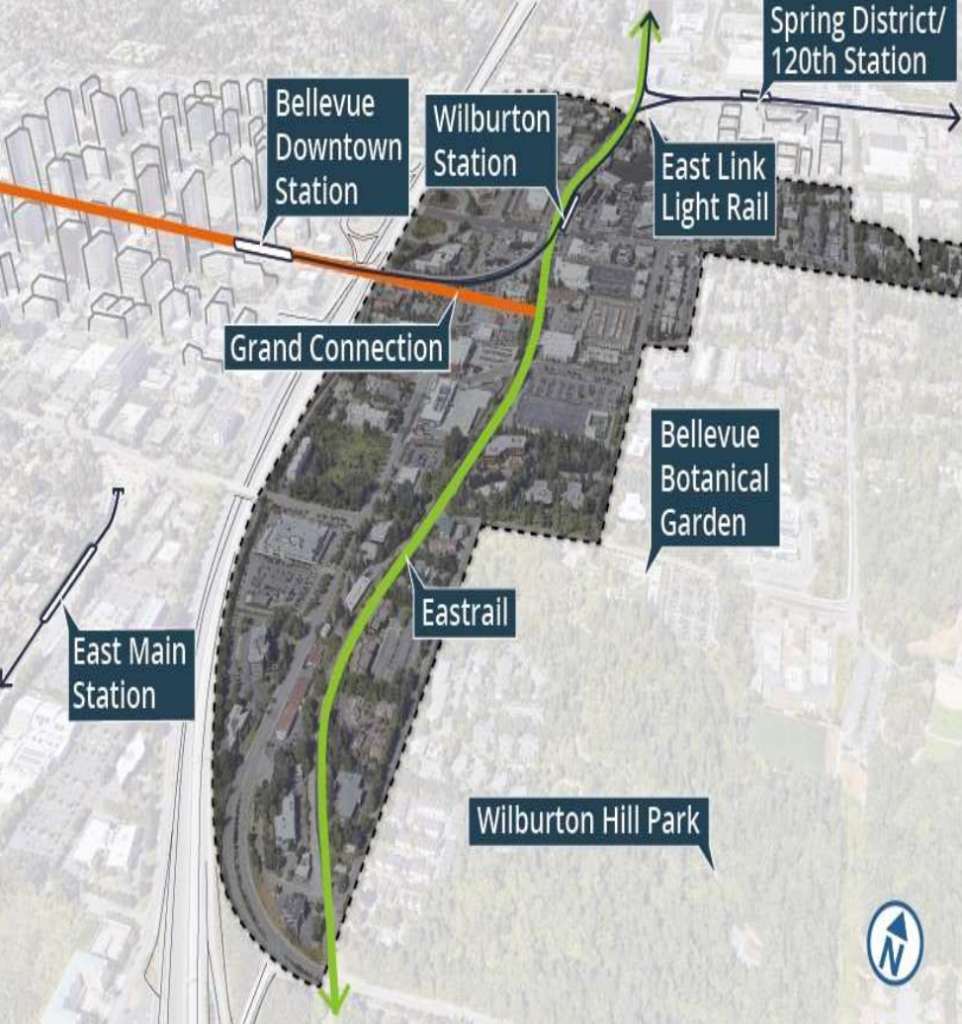

The contrast between Downtown Bellevue Station and Wilburton, the next light rail stop east on Sound Transit’s 2 Line, is stark. Downtown skyscrapers and pedestrian plazas transition to car dealerships and surface parking lots, with the neighborhood bisected by seven-lane, car-dominated NE 8th Street. But the City of Bellevue has grand ambitions for the area, seeing Wilburton’s potential to burgeon into a multimodal hub as the convergence of light rail and the robust and growing Eastrail regional walking and biking corridor.

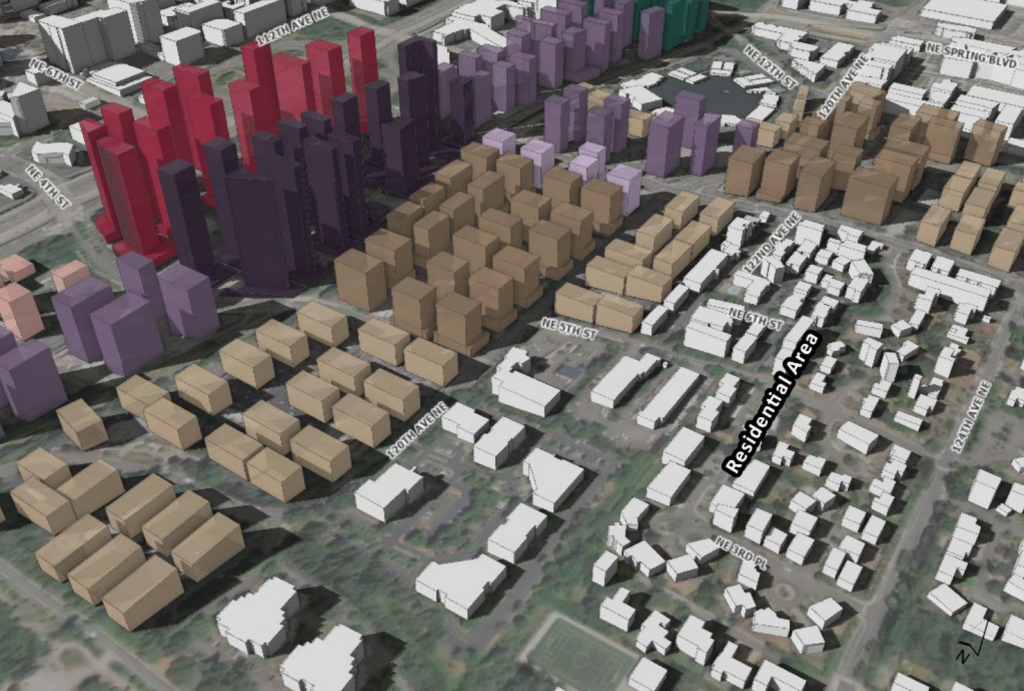

Once the 2 Line extends across Lake Washington to Seattle, which Sound Transit hopes to achieve by the end of 2025, riders in Wilburton will be able to get to Downtown Seattle within 25 minutes and to Downtown Redmond within 15 minutes, and Bellevue wants to prime the area for growth. A Wilburton boom is a key element of the city’s newly adopted Comprehensive Plan, which outlined a vision for creating capacity for nearly 15,000 new homes in the area, with the highest buildings focused between I-405 and the Eastrail corridor to the east.

But now the task is getting Bellevue’s land use code to foster that development, rather than stifle it. For months, Bellevue’s planning commission has been considering a code update that will set the stage for Wilburton’s redevelopment, increasing zoning capacity while at the same time setting requirements that will create badly needed pedestrian and bike infrastructure in the area. In mid-March, the commission unanimously voted to approve a suite of recommendations and send it to the Bellevue Council, which is expected to take it up later this spring.

“Wilburton presents Bellevue, in my perspective, the next major opportunity to replicate the vision of the Spring District, and the rezone would mark just such a pivotal moment in creating thousands of transit-oriented homes that we all know will be alongside vibrant public amenities and trails,” Patience Malaba, Executive Director of the Housing Development Consortium, told The Urbanist.

Malaba is one of the co-chairs of the Eastside Housing Roundtable, a broad array of organizations that have been working behind the scenes to come together on a set of aligned recommendations that will lead to housing growth in Wilburton. Among them: the Bellevue Chamber of Commerce, Amazon, Microsoft, Seattle King County Realtors, Habitat for Humanity, and Plymouth Housing.

“You might think that there’s some strange bedfellows in the roundtable group, but actually, no, most of the folks there are building housing, whether that’s affordable housing or market-rate housing,” Holly Golden, a land use attorney with Hillis Clark Martin & Peterson and a member of the Eastside Housing Roundtable steering committee, told the commission at a hearing earlier this year. “There’s a shared fundamental belief that we should be creating an abundance of housing to solve an affordability crisis, and we need more housing.”

One of the core issues in Wilburton has been whether to pursue an inclusionary zoning (IZ) policy that would require developers to include affordable units in new buildings, or pay a fee that would allow construction of affordable units elsewhere. IZ policies are in place in nearby cities, including Seattle, Redmond, and Kirkland, but not in Bellevue — though the city did dabble in the past.

In 1991, Bellevue was one of the first cities in the region to implement an IZ program, requiring all multifamily development with more than 10 units to set aside at least 10% of units for households making 80% of King County’s area median income (AMI). The results of the program were seen as lackluster, with fewer than 300 units of affordable apartments and condos built over the first five years of the program. In 1996, the program was converted to an incentive-based system, and Bellevue leaders have been reluctant to pursue a similar program ever since.

Now Bellevue is poised to give the idea another go in Wilburton, a move that is aligned with the King County Affordable Housing Committee’s recommendations on how Bellevue should implement its Comprehensive Plan to meet broader regional goals. “If Bellevue increases residential development before or without adopting an inclusionary housing policy, market rate development could occur, representing a significant missed opportunity to create affordable housing units,” the committee wrote to the City last summer.

When Bellevue walked away from its IZ program in the 1990s, the City did not replace the developer mandate with a program directly raising revenue to build affordable housing. Seattle has had a housing levy since 1986, which has raised hundreds of millions since and contributed to the creation or preservation of more than 12,000 affordable homes currently housing an estimated 16,000 people. Bellevue has not gone that route. Even when a funding mechanism dropped in its lap via state legislation, Bellevue opted to go it alone rather than partner with the County on a more ambitious program, which has delayed investments.

“From the start, we’ve seen it as a really necessary part of this whole thing to make sure that we see affordable housing in Wilburton as a critical asset for the success of the neighborhood,” HDC’s Brady Nordstrom told the planning commission. “Community doesn’t exist without that housing and without different ranges and sets of income levels.”

And while any IZ program implemented in Wilburton could serve as a precedent for the rest of the city, unique dynamics have been driving the conversation around what exactly it would look like here. Wilburton’s large blocks, which hinder pedestrian and bike mobility, are going to be broken up as development occurs and the proposed code amendment will lay out standards for those new connections. Because that new infrastructure will be both paid for by developers and ultimately subtract from the amount of space available for both housing, retail, and office space, any affordability mandates added on top will have to take those additional requirements into account.

In the end, the planning commission endorsed an affordable housing mandate of 10% of units affordable to households making 80% of the county’s median income. That 80% AMI level is currently around $90,000 for a family of two. While the ratio matches the requirement imposed in the 1990s, significantly more development capacity will be unlocked in Wilburton. The policy would provide an option for developers to pay a fee that allows the construction of those units off-site, making the program more adaptable. Additionally, a catalyst program will offer the first developers ready to come into Wilburton a discount on the affordable housing mandates.

“It’s fundamentally important to get the calibration right,” Malaba said. “It’s fundamentally setting the goal of affordability and overlooking maybe sustainability instead of housing first, but bringing a balance to both, given that the city has goals on both ends.”

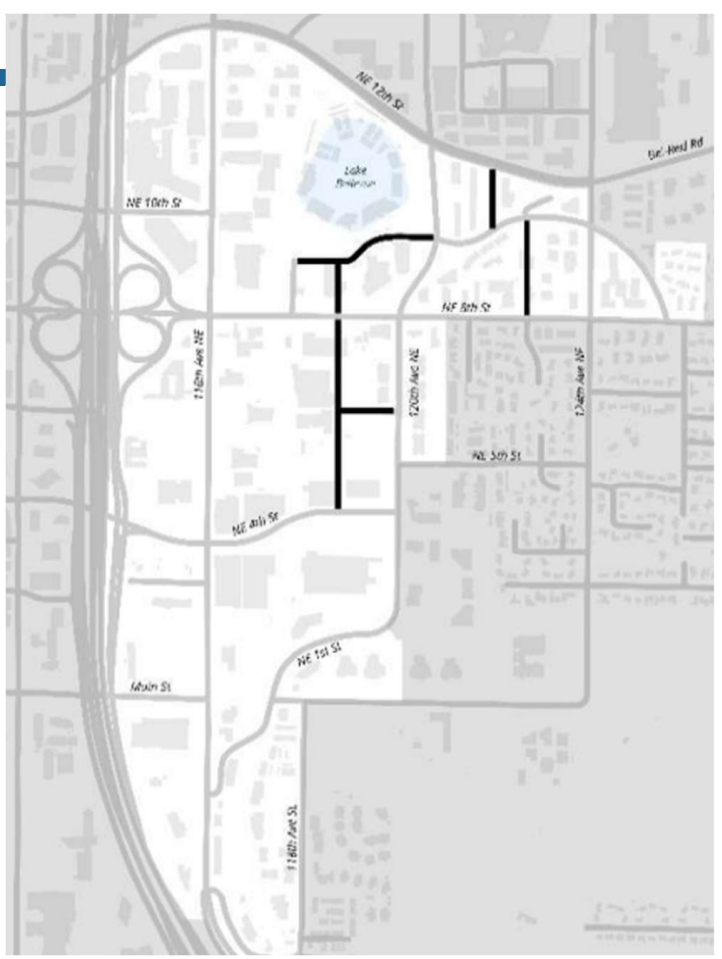

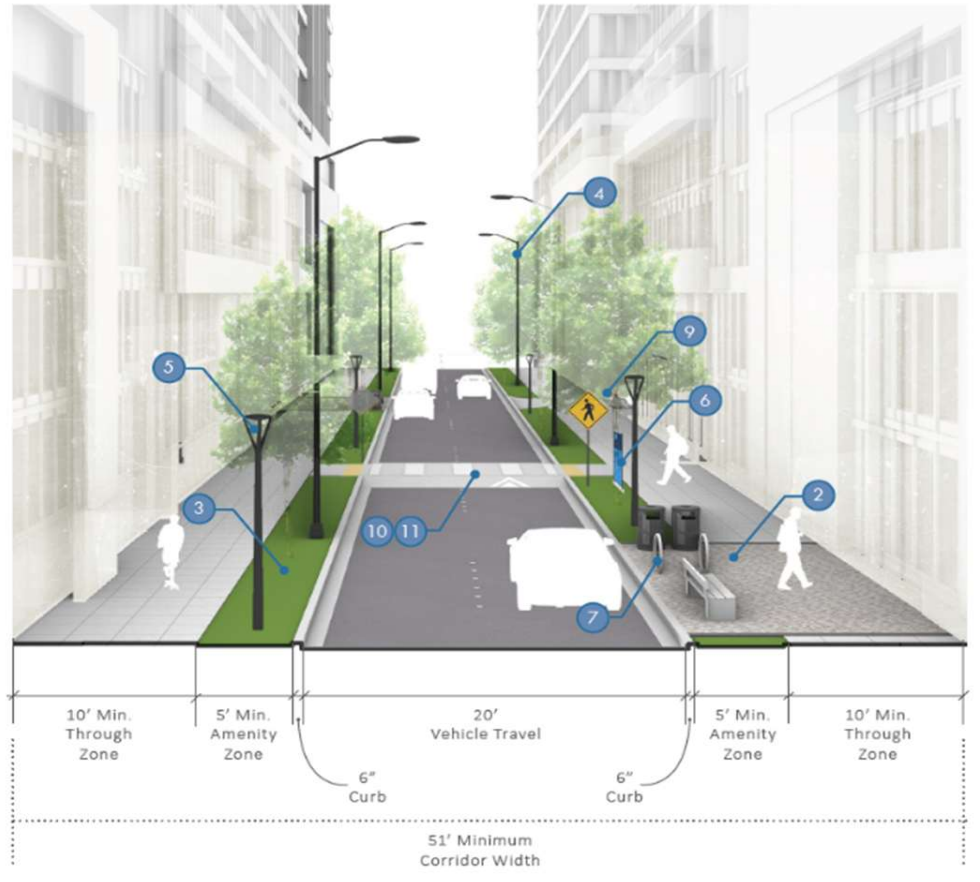

The draft code includes several brand new street connections that would break up Wilburton’s superblocks, a required condition of redevelopment. The exact configuration of these brand new streets has been hotly contested, but the recommendation approved by the planning commission includes a requirement to set aside 67 feet of space, to make way for two 10-foot travel lanes, two eight-foot parking lanes, 22 full feet of curb and amenity zones, and two 10-foot sidewalks. Alternatives put forward but not recommended including shrinking the sidewalks to six feet, which pedestrian advocates view as absurd given the amount of space provided to cars, and eliminating the requirements for on-street parking.

The code also includes requirements for any optional internal street connections beyond those included on the map. More midblock connections would provide big gains for mobility, but making the requirements too onerous could discourage their creation. In the end, the recommendation includes eight foot sidewalks, a reduction from the originally proposed ten, with no on-street parking.

As for off-street parking, originally Bellevue planning staff recommended that all mandates for developers to include a certain number of parking stalls be fully dropped in Wilburton, in alignment with the vision for a multimodal neighborhood.

“With several light rail stations within a 10-minute walk from points within the neighborhood, as well as Eastrail, a major regional trail running directly through the center of the neighborhood, Wilburton finds itself at the epicenter of new transportation opportunities for the region,” a staff report from last March noted. “Taking advantage of this unique opportunity for innovative strategies, and acknowledging the environmental and safety impacts vehicles impose, staff are recommending that parking not be required for new development in Wilburton.”

But in a testament to how far Bellevue still has to go in truly embracing best practices around urban density, that recommendation did not make it to the end of the planning commission’s process. In the end, a 75% reduction in existing parking mandates within the Wilburton area moved forward instead, a move that could still require a significant number of off-street parking in new development that is intended to be transit-oriented, adding housing costs that get passed onto future tenants.

The Urbanist has detailed the self-defeating nature of Bellevue’s intense parking requirements before, and while that trend looks poised to continue in Wilburton, the city at least appears to be inching in the right direction. But ultimately, any parking mandates are likely to cut against the city’s own goals, and certainly won’t help Bellevue’s reputation as a fully car-focused city. (A statewide parking reform bill could also prove to be a big help here, exempting smaller commercial spaces along with affordable housing.)

While the planning commission has officially made its recommendation, debate over all of these elements will almost certainly continue up until a final council vote. And while all of these components work together and determine whether projects will truly be able to pencil, the core of the package — the affordability mandate — seems to be firmly set in place at this point.

“As we move into this affordable housing era, where we’re talking about putting a tax of $10,000 per unit on a housing unit, we really need to find ways to reduce the cost of producing the housing and achieving the density in Wilburton,” developer and former Bellevue Councilmember Kevin Wallace told the commission.

But if Bellevue is able to get that balance right, the dividends could be huge. Now it falls to the Bellevue Council to decide whether to get on board.

“This is, in my mind, a once-in-a-generation opportunity for them to move forward inclusive housing growth in Bellevue,” Malaba said.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.