Bremerton’s two-decade quest for a safer and more pedestrian friendly 6th Street is approaching a decisive moment, one that current city leaders appear poised to let slip by. The Greg Wheeler Administration has presented its preliminary (30%) designs for the 6th Street Active Transportation Project, which includes just a single, car-centric option. The administration is trying to muscle through its design, requesting that the Bremerton Council provide $394,000 to “advance conceptual alternatives to final engineering.”

When a design is finalized, the City is confident it will have $3 million in federal funding via the Puget Sound Regional Council, barring Trumpian chicanery.

Several members of the Bremerton City Council have voiced strong support for making 6th Street a safe, multimodal street and they have arrived at their final movement of leverage. If it approves the administration’s funding request, they won’t have another opportunity to influence design before it’s all but final.

Safe streets advocates are pushing back against the mayor’s plan, demanding that a second, safer design be considered, which would slow cars, add protection to the bike lanes, and make intersections safer.

At stake is not just 6th Street – the most direct east-west multimodal route in Central Bremerton — but also the future of Bremerton’s active transportation ambitions. If the City is unwilling to create adequate space for non-vehicle transportation on 6th Street, the multimodal transportation revolution that Bremerton needs will probably never be viable.

A battle for limited space

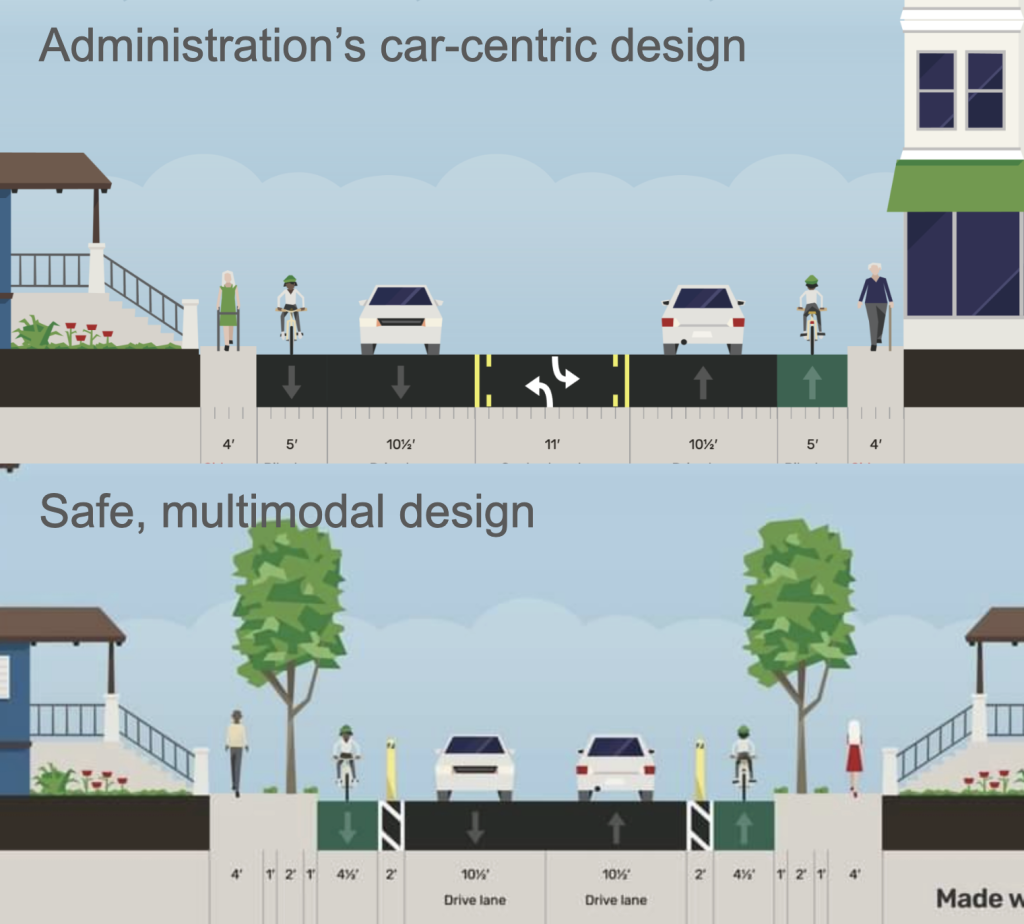

The core challenge on 6th Street is space. 6th Street is a narrow four–lane arterial, 44 feet wide in the straightaways and 50 feet wide at major intersections, with narrow four-foot sidewalks that are inhospitable to people with disabilities. The Administration’s plan is to reduce the four-lane street to three vehicle lanes. That creates about 11 feet of new space.

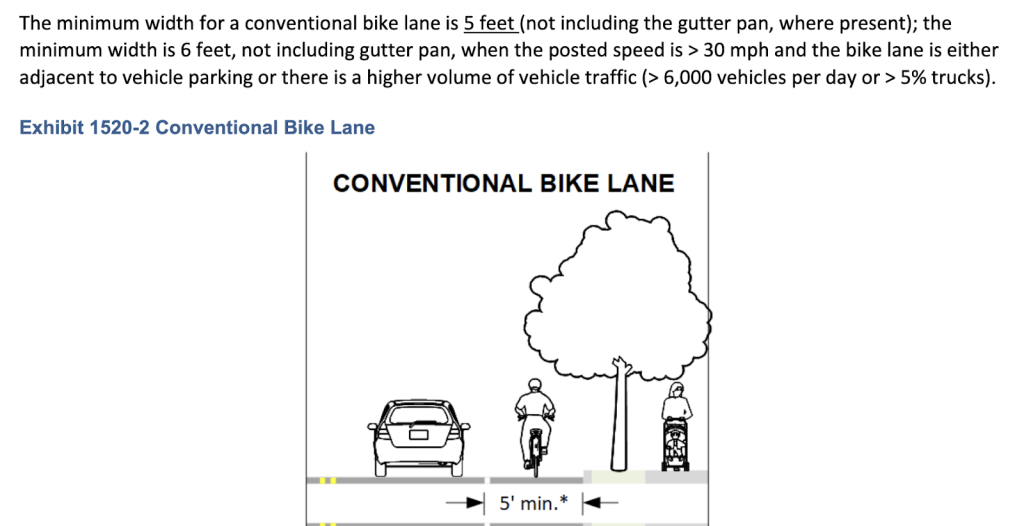

Unfortunately, this is not even enough space for regulation-width unprotected bike lanes. WSDOT guidelines recommend that bike lanes be 6 feet wide (not including gutter pan) – each side has room for a 3.5-foot bike lane + 2-foot gutter pan. WSDOT guidelines for protected bike lanes require a minimum width of 7 feet (not including the gutter pan).

The Wheeler administration has so far refused requests from City Councilors and citizens to study a safer option, with traffic calming, protected bike lanes and pedestrian safety improvements at crosswalks.

“We’re not able to build all ages and abilities facilities… [or] provide a separated or protected bike lane with a five-foot bike lane and a two-foot buffer, unless we eliminate the center turn lane,” Bremerton City Engineer Ned Lever said at a January 8, 2025 study session.

Lever is correct: if the Administration forces through a 6th Street with end-to-end center turn lane, then safe, multimodal travel will not be possible on the street. Conversely, if the City decides that multimodal travel is a priority for 6th Street and builds safe infrastructure for residents, students and shoppers, cars would lose the ability to turn left reducing rush-hour traffic speeds.

How much traffic is there, really?

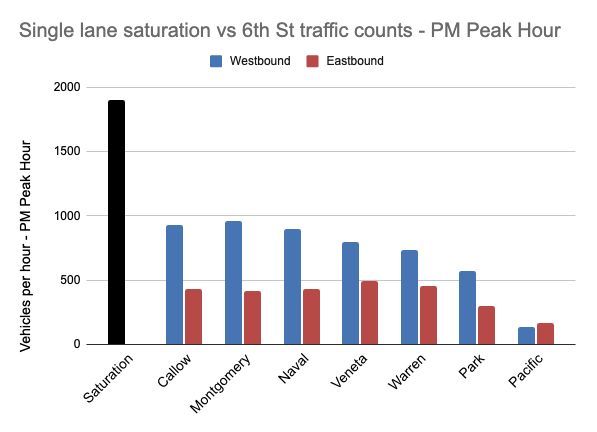

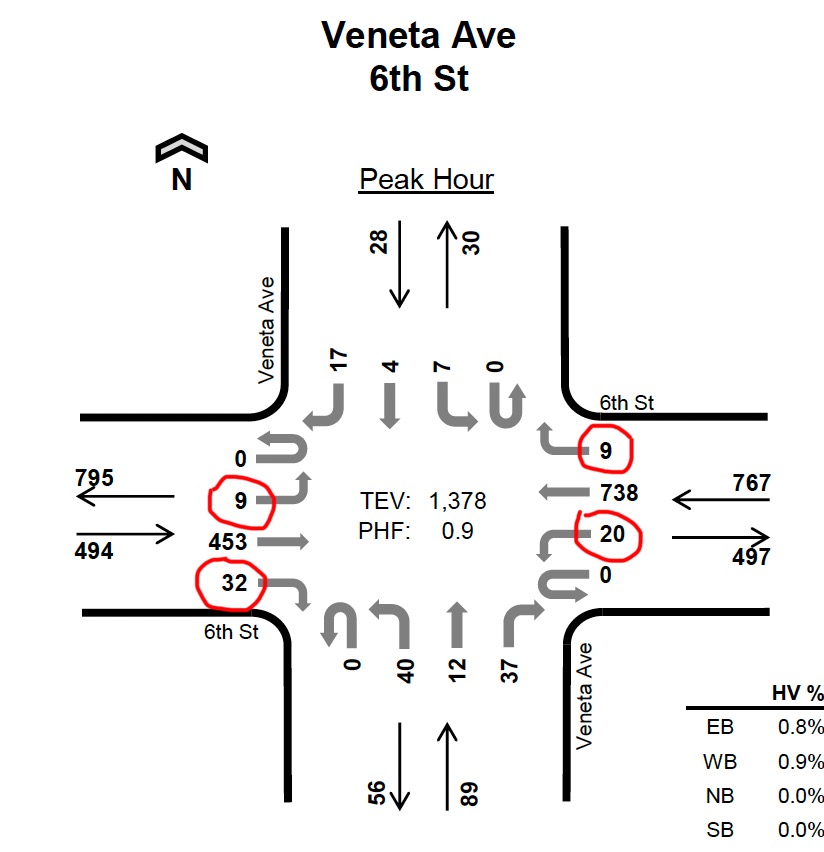

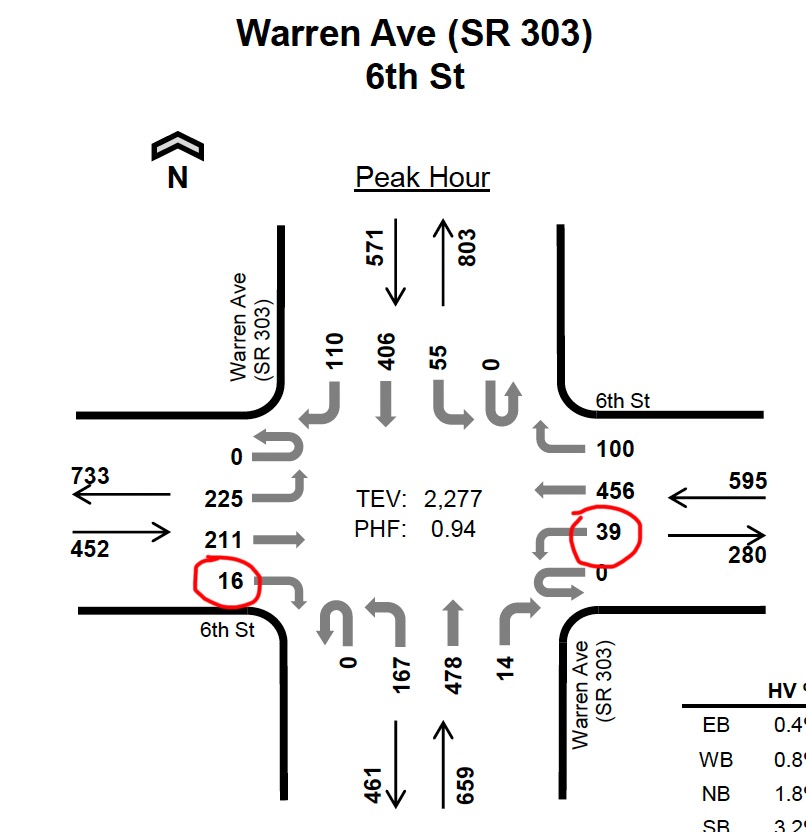

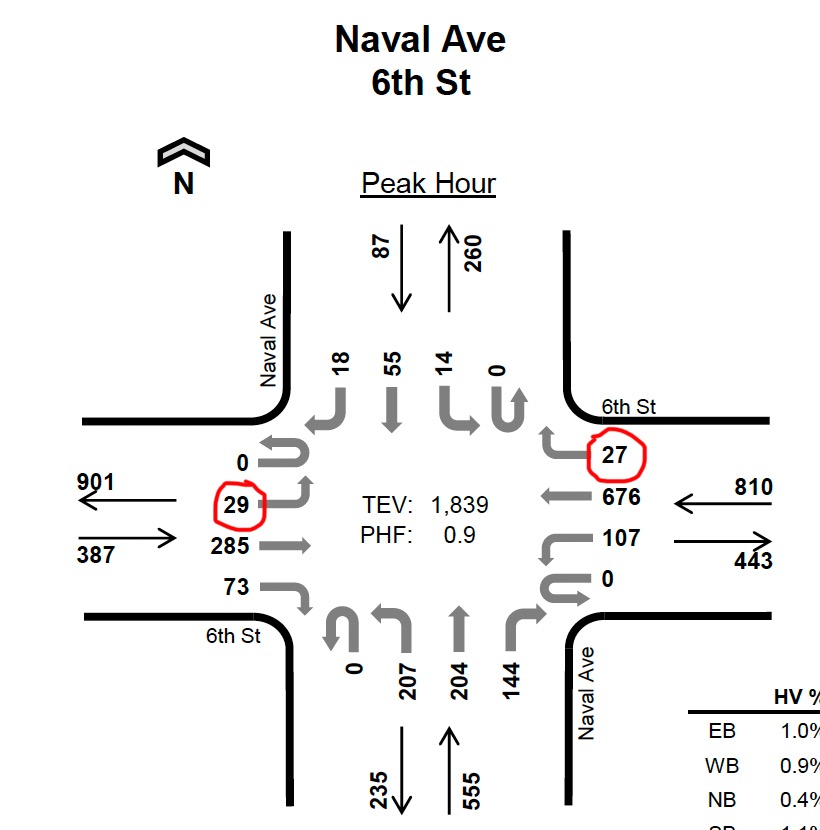

Peak hour traffic on 6th Street is quite modest. Traffic engineers use the concept of ‘saturation flow rate’ to determine the theoretical maximum traffic that a street can handle, for a single-lane street, the saturation flow rate is 1,900 vehicles per hour. No section of 6th Street carries more than 960 cars, during any one-hour period, according to a 2024 City of Bremerton measurement (not a full study, I was informed).

The 2024 traffic measurement counted traffic along 6th Street’s major intersections during two ‘Peak Hour’ periods, AM and PM*. The traffic study set ‘Peak Hour’ as 3:30-4:30pm (AM peak hour 6:15-7:15 has significantly lower volumes.) Even looking at the highest single-direction traffic measurement, no part of 6th Street came anywhere near 1,900 vehicles per hour. That supports advocates claims that 6th Street would function fine, without the end-to-end turn lane.

Tangentially, the focus on a single hour is in technical violation of BMC 11.12.050(o) which states: “Peak period” means the two (2) hour a.m. or p.m. period during which the greatest volume of traffic uses the road system impacted by the project traffic. The one-hour focus exaggerates vehicle traffic (averaging across 2-hours produces lower traffic measures) and is an example of the long-standing pattern of the Wheeler Administration putting its foot on the scale for single-occupancy vehicle travel, at the expense of multimodal travel.

Two-lane design is safer than three

Bremerton’s City Engineer recently claimed, without evidence, that two-lane streets are more dangerous for cars than three-lane streets.

“So we’re not going to be able to provide a separated or protected bike lane… unless we eliminate the whole center turn lane,” Lever said. “And that eliminating the center turn lane has safety implications for drivers. That’s when you’re going to get road rage, rear-enders and you know, you’re going to have queuing.”

Bremerton officials seem more concerned about preventing fender benders than the safety of non-car users.

The City’s frequently repeated assertion that two-lane streets have more collisions than three-lane streets is unsupported. A study from UCLA by Michael Rosen, which showed that Los Angeles streets that were reduced from 3 to 2 lanes had 42% fewer crashes and 108% fewer severe and fatal crashes, than streets that remained three lanes. There seems to be no evidence that three-lane streets eliminate road rage.

A 2013 Federal Highway Administration literature review found favorable results almost universally for the various road diets cities have attempted. Reducing car lanes and adding protected bike lanes, particularly on pedestrian-focused streets, is a data-driven solution that improves safety for all.

Fixing the Intersections

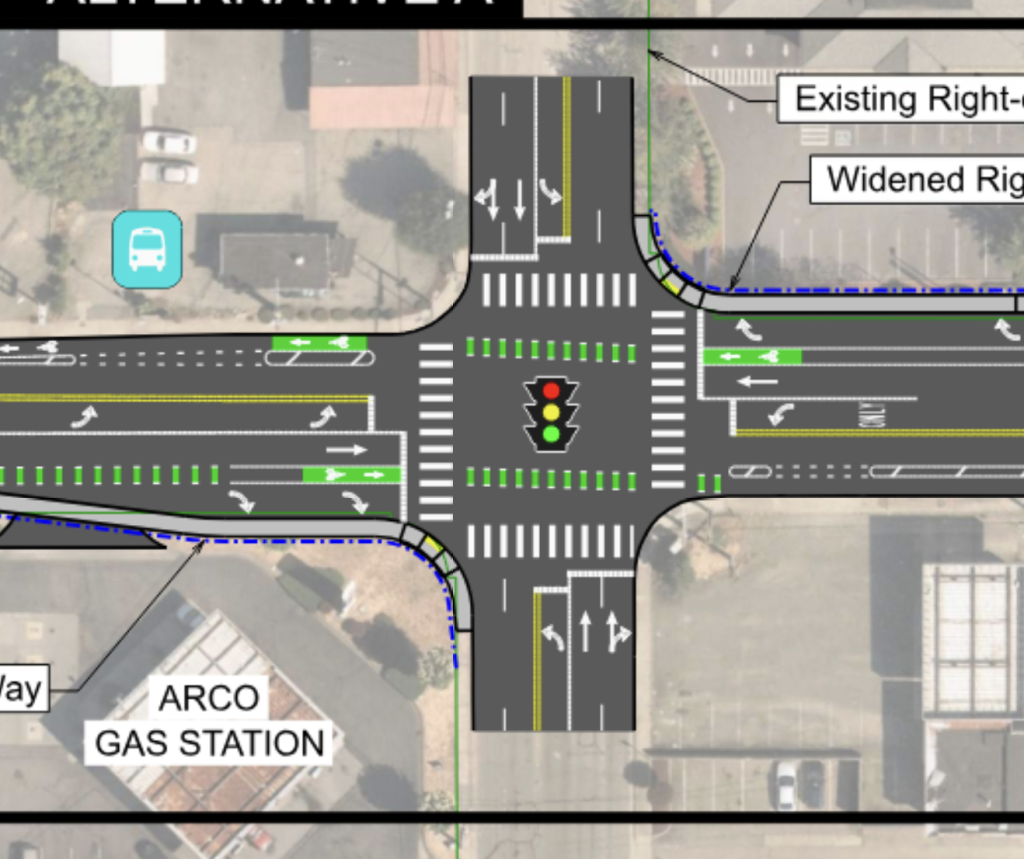

The Wheeler plan for 6th street maintains both left and right turn lanes at major intersections, which precludes building a safe multimodal facility. The intersection of Naval and 6th is the worst example. The design calls for bike lane ‘mixing zones’ in which a person biking ends up between two lanes of cars, a deeply uncomfortable riding scenario.

A safer design would eliminate one turn lane. This is possible because the City’s 2024 traffic measurement proves that very few vehicles turn in certain directions. For instance, let’s look at the highest traffic intersections of 6th Street (Callow, Naval, and Warren). Each of these intersections have at least one turn direction with fewer than 40 turns during PM “peak hour.”

In other words, during the busiest time per day, the turn lane accommodates less than one car per minute. Removing such a little-used turn lane would have negligible effects on traffic. And that extra 10 feet of space creates the opportunity to build safer crosswalks, bicycle protection and slow down turning cars. The Wheeler Administration’s design favors a tiny number of turning cars over the safety of people outside of cars.

Where would (moderate) traffic go, if not 6th?

Safe streets advocates argue 6th Street doesn’t need to be a car thoroughfare because within nine blocks, it is flanked by major, high-capacity routes: 11th Street and Burwell Street (SR 304). Both 11th and Burwell have much higher traffic than 6th. Both are ‘US National Highway System’ arterials, 6th is not. And neither arterial is yet at capacity.

There is little likelihood that traffic diverted from 6th Street would end up on residential streets. That’s because no residential street stretches the full distance east-west in Central Bremerton like 6th, 11th and Burwell do. Finally, 6th Street does not connect directly to major destinations as 11th street and Burwell do.

Build it right

Prioritizing multi-modal safety on 6th Street would revolutionize life in Central Bremerton and make the street a postcard of Bremerton’s ‘good life.’ 6th Street has been planned as a multimodal street since at least 2007 making cameos in the 2007 Downtown Subarea Plan, 2007 Non-Motorized Transportation Plan, the 2018 Complete Streets report, the 2019 Corridor Feasibility Study and the 2023 Joint Compatibility Transportation Plan.

6th connects the three-quarter miles between two of Bremerton’s most walkable neighborhoods, Downtown and Callow. 6th has dozens of pedestrian-oriented developments on or just off it, including five schools, three churches, a major city park, local businesses, the City’s largest homeless shelter, and City Hall.

Even if the ‘safe street’ vision is wrong, and even if it is determined that Bremerton be held to prioritizing 6th as a fast-car street, the debate should not be curtailed. The City deserves to see a viable second design that hews closer to the safety-oriented vision for the street and thus our community. Then a proper process can ensue, and may the best design win.

The Wheeler Administration’s efforts to force through their favored, car-centric design that is hostile to people walking, rolling, and biking, without studying safer viable options is wrong and wasteful. When City Council allocated $700,000 to study options for 6th, multimodal travel was high on their wishlist. The Administration has spent $191,000 so far, with no fully multimodal option presented; a gross misuse of funds.

The City deserves a real debate about the fate of this most important street. Bremerton must at least consider innovative streets ideas and new street safety standards. Residents and voters deserve to be heard and given the same consideration as out-of-city commuters.

City Council must hold their ground and require the administration to offer more than one proposal, one or more safer, viable, multi-modal design options.