While Seattle has cycled through carshare startups, Vancouver’s Evo program has boomed, aided by strong transit and less competition from ridehailing.

After approximately three and a half years of operation in Seattle, Gig Car Share, a carsharing service that provided one-way short-term car rental services, ceased operations in late December. Citing high operational costs and overhead as well as insufficient demand, the American Automobile Association (AAA)- owned program was pulled from Seattle, San Francisco, Oakland, and Berkeley. It had already pulled its Sacramento fleet for the same reasons in 2023.

Gig Car’s dissolution eliminates a major tool for Seattleites who don’t own cars or are hoping to forgo car ownership in the future. While roundtrip service carshare programs such as Zip-Car still exist, the loss of Gig represents the end of any one-way carshare service in Seattle. The AAA’s statement that its decision to end operations may suggest that this type of service is unfeasible, however, less than 150 miles away on the Canadian side of the border, carshare services in Vancouver, British Columbia paint a very different story.

Despite a national border, the two cities probably have more in common than they do with many others in their respective countries due to their geographical proximities, similar demographics, and topography. If carshare works in Vancouver, it can work in Seattle — at least if the City designs the right program and fosters the proper conditions for both carshare and residents’ broader mobility to flourish.

Free-floating carshare services provide a valuable service for urban residents aiming to reduce their car dependency. When going completely car-free can prove difficult or unfeasible for many residents of North American cities where governments have historically opted to subsidize and prioritize parking, urban sprawl and highway expansion, free-floating carshare programs can fill in the gaps in people’s needs without committing to full ownership.

Unlike similar round-trip carshare programs, where users must return cars where they picked them up, free-floating carshare programs allow members to leave the cars in different places than where they found them. This means that if users take a car to do errands or visit a friend, they can leave the car and only pay for the trip itself rather than having to keep the car on retainer and pay for the inactive time.

Carshare also can incentivize chaining different types of transport together. Running late to meet friends at the pub? Rent a carshare to get there then bus home safely! Evidence suggests that users of free-floating carshare programs are more likely to use it to complement public transportation than round-trip carshare users.

In practice, Gig and Vancouver’s Evo are almost identical services, right down to the black and blue branding and their respective fleets of Toyota Priuses. Both require members to sign up for a low-cost membership after which they book cars through an app and leave the cars anywhere within their respective home-zones (specific areas within city limits where the cars can be parked). Users are charged per minute, by the hour or per day depending on the length of the ride’s usage. In both cases, the services had arrangements made with their respective cities to allow parking in resident-only or paid parking spaces.

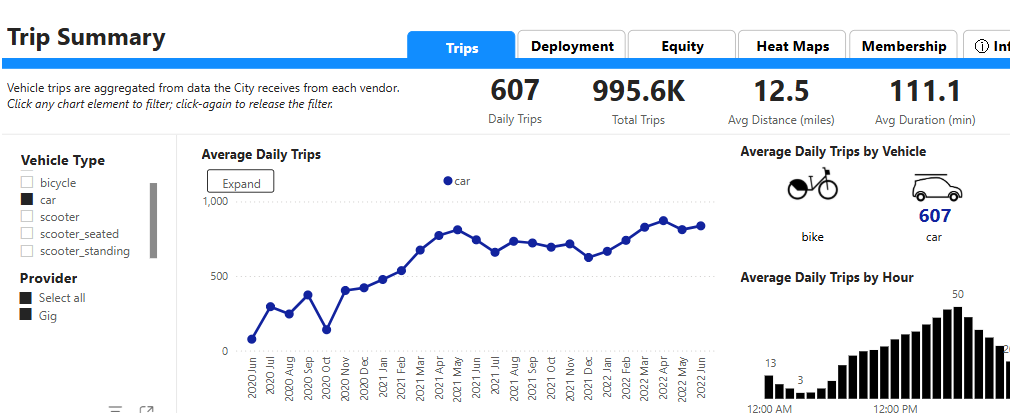

Even at its peak however, Gig never reached 900 daily rides according to publicly available data from the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT). While specific ridership data is not available for Evo, the company says its Vancouver fleet is approximately 2,300 cars (compared to Gig’s peak in Seattle of 400 cars), suggesting that its regular ridership is likely much higher than Gig’s was.

So, what explains the difference between Evo’s ongoing success in Vancouver and Gig’s collapse in Seattle? Two key reasons are advertising and the availability of complimentary transportation services.

Evo invested in advertising

Gig faced an uphill battle from the beginning. Initially launching in Seattle in June 2020, the service faced a slow start because of the pandemic, causing both fewer people to go out as well as fewer opportunities for potential customers to be reached through traditional advertising. Looking at the SDOT-provided graph on Gig ridership, it took approximately a year for the service to hit its stride. Promotional efforts were limited to advertisements on city buses, messages printed on the cars themselves, and online advertisements. While all useful strategies, these were not enough to get Gig out of its slow start in a way that was sufficiently profitable for AAA.

Evo in comparison has had a much more aggressive advertising strategy. As well as ads on buses and their cars, it has pursued other community-oriented approaches to integrate the service into daily life for residents.

For example, Evo makes a concerted effort to reach out to university students, stationing tents at campus orientation events to offer free trials and membership to students at the start of the school year. This targets a non-car-dependent demographic, potentially creating long-term users if they come to rely on the service. Evo also has arrangements for set parking spaces at schools like the University of British Columbia, Simon Fraser University, BCIT, and Capilano University to support on campus usage.

Another example is Evo’s Summer Cinema series, where Evo sponsors free outdoor movie nights in Vancouver’s Stanley Park holding up to 8,000 attendees. As well as building name-brand recognition through these community events, Evo can also prioritize its own service by providing dedicated parking spaces for its vehicles.

Vancouver’s richer transportation ecosystem

While Vancouver’s public transit and bike lanes move around the city, Seattle’s in comparison places a higher priority on car ridership and connecting neighborhoods to the downtown core. If you’re in the city of Vancouver, most bus routes will be a fairly straight shot whatever other neighborhood you need. While there may be transfers, you will generally find yourself moving towards your destination at all times. Seattle in comparison will frequently see you bus into downtown and transfer out to a different direction. Notably, the 99-B Line route in Vancouver is the busiest bus corridor in either Canada or the US yet it does not pass through the city’s downtown core.

Coupled with a freeway plowing straight through the city (Vancouver is notably the only major city in North America to avoid this fate), busing between parts of Seattle that are under a 20-minute drive might take you closer to an hour to bus. As a result, driving is often the most cost-effective means of transportation for those who already own a car (ignoring the societal costs increased car usage causes to public health, public safety, and the environment). All this has resulted in significantly higher transit ridership in Vancouver than Seattle.

Reducing car ownership is one key to the success of carshare services. While saving money is frequently cited as a positive of carshares, the marginal cost (what one extra trip will cost a user) of using carshare services will almost always be more than that of using one’s own car since users must absorb the per-trip cost of gas and insurance while allowing paying enough to keep the ride-share organization afloat. However, moderate-to-infrequent drivers will save money in the long run as they avoid the overhead of car ownership.

In other less econ-nerdy terms, if you already own a car, it’s cheaper to use that rather than pay ride-share fees. To convince people to reduce car ownership and use carshare programs, carshares need to complement an existing transportation ecosystem that supports reducing car dependency and ownership.

Seattle’s transit network and bike lanes are improving but remain insufficient to entice most people out of car ownership. Seattle’s transit network falls into a radial system, a type of transit style that prioritizes connecting neighborhoods to a city’s downtown core with a lesser focus on connecting non-downtown neighborhoods to one another. While radial transit networks are good for connecting residences to workplaces, it limits the ability of transit riders to move between different neighborhoods. This manifests itself in significantly higher transit times for those moving between non-downtown neighborhoods compared to driving, as well as prioritizes public funding towards a specific class of worker deemed to be the standard because they spend their time in the prioritized downtown core.

Conversely, Vancouver’s transit system network with its multiple SkyTrain routes has a more inter-neighborhood connection style that supports activity beyond going to and from work.

Vancouver is hardly perfect, and car-ownership rates can still vary greatly between neighborhoods. Looking at Vancouver on the sub-neighborhood level shows that while more than one-third of residents are carshare members, highly transit-serviced neighborhoods such as Kitsilano or near the Port of Vancouver see that number increase to close to half while more suburban areas in the city with less transit service see that number fall as low as 21%.

Car ownership in Vancouver is also inverted with carshare membership, with higher rates of car ownership occuring in neighborhoods where carshare membership is lower. This makes sense, as a study that found that 25% of carshare users in BC said they reduced their vehicle ownership after joining a carshare program and 40% said that access to carshare programs discouraged them from buying a vehicle they would have purchased otherwise.

Despite inconsistent carshare service, Seattle’s car ownership rate has managed to decline, with car-free households surpassing 20% in 2023 according to Census data. Vancouver’s proportion of carshare households is only marginally higher at 22%. Reducing car-ownership doesn’t seem to tell the whole story.

One key differentiator, however, is that 53% of daily trips made by Vancouverites are completed by active or public transportation while comparable 2019 data from the City of Seattle finds that 66% of trips are completed by car.

So despite having relatively similar total rates of household car ownership, car reliance appears to be lower in Vancouver, resulting in people relying on multiple modes of transportation and using cars to fill gaps when needed. A positive correlation exists between carshare membership and transit service, and an inverse one with membership and car-ownership. Accordingly, it seems that Evo’s success is dependent on key non-car dependent neighborhoods, while more car-dependent ones bring the city’s overall household car-ownership average back in line with Seattle’s.

Other factors that could be affecting the difference in uptake could be the availability of other transportation options. For example, ride-hailing services like Uber and Lyft were not permitted in Vancouver until January 2020. This meant that ridehailing was not a feasible alternative service to carsharing while companies like Evo were first establishing a customer base, while Gig was always competing with ridehailing services.

Another competitor could be the relative availability of micro-mobility options. Vancouver only recently began piloting scootershare in through lime in select neighborhoods in Fall 2024. Mobi, the Vancouver based bike share program owned by Roger Communication, has only recently expanded its geographic coverage to be accessible to half of city residents and this distribution has been noted to be highly uneven from a socio-economic perspective.

On the other hand, Lime bike essentially covers all of Seattle barring some restricted areas. It’s not a surprise then that bike and scootershare programs have had a greater uptake in Seattle. In 2023 nearly five million shared bike and scooter rides were recorded while Mobi (the only player in the Vancouver market at the time) recorded just over one million trips for the first time ever that year. It may be possible then that the greater usage of micromobility options in Seattle absorbs a lot of the last-mile demand that rideshare takes up in Vancouver.

There is still work that needs to be done in Vancouver to ensure all residents have access to the infrastructure to reduce car dependency, but as it stands, there appears to be sufficient demand to support carshare services as a business model.

Can Seattle lead again?

Gig Car’s closing may seem like a foregone conclusion of a business model that simply doesn’t work. It’s worth remembering Gig Car isn’t the first time one-way carshare has been introduced in Seattle. In 2019, Car2Go, a similar service operating in cities internationally faced similar issues and shut down all its North American locations due to similar issues. But a comparison with Vancouver shows that one-way carshare programs can be feasible with the right support and public infrastructure.

At one point Seattle could have been seen as a leader in promoting carshare programs. For example, a 2018 thesis from Simon Fraser University found that the City of Seattle was initially a leader in supporting carshare programs, pioneering policies that the City of Vancouver would end up using such as allowing free parking for the services in metered spaces and residential-only spots, an action that was highlighted by a representative from Evo as crucial to a conducive car-sharing market. Interviews conducted with City staff in this thesis highlight that this is not a coincidence; Vancouver was directly inspired by actions taken in Seattle. And there was certainly enough demand for residents to see it as a lifestyle change. An SDOT study from the heyday of Car2Go found that 14% of users indicated that they had given up owning a car since joining the service.

What is evident is that carshare services are not a silver bullet to reduce pollution and traffic collisions. carshare services need to be a support player in building a wider transportation system that is built around people rather than cars and works in tandem with public transit options rather than competing with them.

While an ill-timed pandemic rollout and slow advertising of Gig Car left a lot to be desired, the fact that free-floating carshare programs continue to flounder in most American cities suggests more structural issues need to be addressed. It’s a new technology presenting exciting urbanist opportunities, but at the end of the day, old transit solutions and solid urban planning are still the bedrock to reducing car-dependency.

Sawyer Junger

Sawyer Junger is a policy analyst who has worked on environmental and municipal issues for governments in both the U.S. and Canada. He is passionate about sustainable infrastructure that supports environmental justice while keeping residents healthy and happy. Sawyer holds a Master of Public Policy from the University of Toronto and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of British Columbia. He's a big fan of bikes, beer league hockey, and CanCon music.