The Seattle City Council is officially overhauling its One Seattle Comprehensive Plan schedule in the wake of a set of appeals seeking to scale back Mayor Bruce Harrell’s plan. Instead of advancing permanent legislation in coming weeks, the council will consider legislation that’s intended to be a temporary stopgap to comply with new requirements in state law, upzoning residential neighborhoods across the city to allow four units on all lots, and sixplexes near bus rapid transit and light rail.

While labelled an “interim” move in technical jargon, the package will ultimately set a strong precedent for what those upzones look like long-term, even if the council will need to circle back and make them permanent.

Upzones creating Harrell’s 30 proposed neighborhood centers and narrow half-block-deep corridors of transit-oriented development around frequent bus routes would have to wait under the revised schedule. These areas would grant new opportunities for apartments and mixed-use multifamily development expected to generate the bulk of new affordable homes in the plan.

While the schedule changes have been signaled for a while, it was made official in an email sent late last week by District 3 Councilmember Joy Hollingsworth, who is chairing the council’s Select Committee on the Comprehensive Plan.

A day earlier, Seattle Hearing Examiner Ryan Vancil cleared his calendar for a potential 12-day public hearing in late April and early May, in which he’ll hear from the six individuals and groups who filed appeals against the One Seattle plan’s environmental review. The appeals come from residents of the city’s most exclusive neighborhoods including Hawthorne Hills, Mount Baker, and Madison Park. While many of the claims raised in the appeals will likely be found invalid under state law, some may move forward and could delay implementation of the plan by several months.

“While these challenges are being considered, the Select Committee will transition to considering interim legislation to implement Washington State House Bill 1110,” Hollingsworth wrote. “The Select Committee aims to conclude consideration of interim legislation by May 30, 2025 due to state compliance deadlines. The Select Committee will also hold another public hearing before May 21, 2025, where the public will be able to weigh in on interim Middle Housing legislation. Notice of the public hearing date will be issued at least one month in advance.”

At council briefing, Dan Strauss says that he has been removed as the vice chair of the select committee on the Comprehensive Plan, and replaced with Mark Solomon. He says that Sara Nelson never directly told him this change was happening and calls the move highly unusual.

— Ryan Packer (@typewriteralley.bsky.social) March 10, 2025 at 2:38 PM

With a drop dead compliance deadline of July 1, the new timeline seeks to give the council some additional buffer. Given many councilmembers’ inexperience on land use issues, they may need the buffer. Council President Sara Nelson appears to be betting that newcomers can rise to the occasion after removing Dan Strauss as vice chair of the select committee earlier this week, even though he is the longest serving councilmember and has land use expertise, whereas new appointee Mark Solomon does not. Strauss and Nelson have often sparred about land use issues, including Nelson’s SoDo stadium housing district proposal.

If Seattle doesn’t adopt these upzones itself, a model code created by the Washington Department of Commerce automatically takes effect. While initial drafts of that model code in 2023 disappointed housing advocates by leaving significant development capacity on the table, a final draft in 2024 was much more robust and would represent a more ambitious code than the one Seattle is likely to allow. But even more than the technical differences between the two codes, the very act of having the state’s largest city adopt a model code rather than one it created itself is something that the Harrell Administration appears intent to avoid.

The select committee is set to hold its first discussion on an interim ordinance on March 19, but actual legislation has not yet been submitted. When it is, it’s likely to be similar to the proposed permanent regulations released by the Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) last year. The looming question is how the council will seek to amend the interim ordinance.

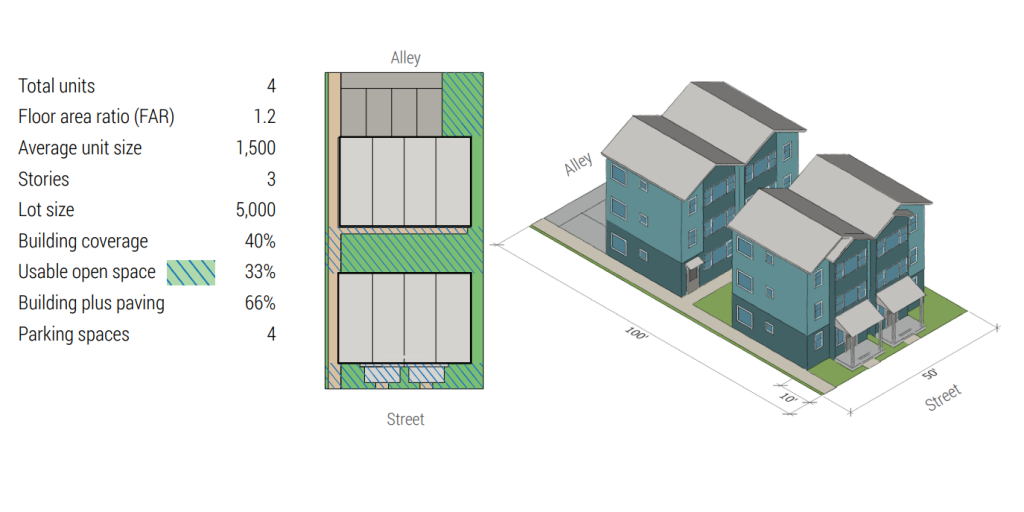

While many new sideboards for neighborhood residential zoning are laid out in state law, a few levers remain that councilmembers could pull that would have a big impact on the legislation’s actual effectiveness. Those include increasing setbacks, reducing lot coverage, and decreasing the amount of space buildings can occupy on a lot, a measurement known as floor-area ratio (FAR). But at least one councilmember has signaled interest in pursuing what some homebuilders consider an outright poison pill for middle housing in Seattle: an affordability mandate.

Last year, the Harrell Administration announced that it wouldn’t be seeking to extend the city’s existing Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) into the new neighborhood residential zones as part of any upzones there. The MHA program as it exists today includes requirements to either build a certain number of affordable units on site or for developers to pay a fee that subsidizes the construction of below market-rate units elsewhere. But on the scale of four to six units, mandating affordability is going to be considerably less feasible than it is in the city’s denser neighborhoods.

Under HB 1110, homebuilders can add two units to development in areas where only fourplexes are allowed as long as those additional two units are kept affordable. But Councilmember Cathy Moore — one of the council’s biggest skeptics of the One Seattle plan — has said she’d like to see Seattle go even further, requiring that the city only grant increased density to the new base level required in HB 1110 if affordable units are included.

“A decision was made not to look at applying MHA in neighborhood residential, and I think that that’s a missed opportunity,” Moore said at a committee meeting in late January. “1110 says that the local jurisdictions are able to utilize their own affordable housing tools and laws to make that happen. And I would really like to explore the idea that if we’re going to have four units on every lot, why can’t we make two of those affordable? Why can’t we make two of those 60% AMI [area median income] or even 80 to 100% AMI?”

Moore brought up the issue a week later, signaling this wasn’t just a passing thought. “We[‘ve] got to vote on 1110, and I think there’s a lot of room to actually make 1110 deal with some of our affordability issues, which are absolutely a crisis in this city. Simply building more rental property for private equity to own is not the answer.”

If builders chose to provide affordable units on-site in Seattle right now within MHA zones, the required percentages required vary from 5% to just under 11%, numbers that are only feasible given the number of additional units granted within upzones in the particular zones. Requiring affordability inside neighborhood zones, where the number of units is much less, is one way to ensure that very little middle housing actually gets built. Then again, that might be an outcome Moore is fine with, having previously inveighed against a proposed neighborhood center in Maple Leaf as “sacrificing” a beloved neighborhood.

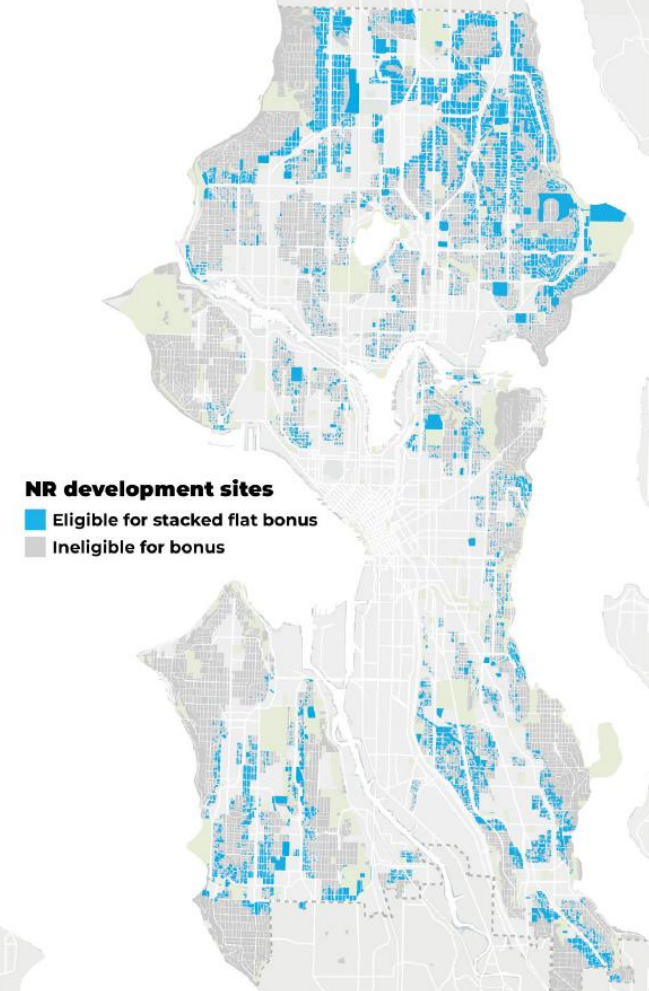

There are also levers that the council could pull that would take the neighborhood residential code in a more positive direction. Seattle’s Planning Commission has been pushing for an incentive program for stacked flats to be expanded, beyond the minimum 6,000-square-foot lot-size requirement that has been proposed. As it currently stands, the incentive would disincentivize the construction of stacked flats in some of the city’s most amenity-rich neighborhoods where most or all of the lots are below that 6,000 foot minimum, even the idea of encouraging an alternative to townhouse development is a point of near universal agreement.

“[W]e recommend removing the proposed 6,000 square foot lot limitation and allow for the 1.4 FAR bonus throughout all Neighborhood Residential zones, not just on lots over 6,000 square feet within one-quarter mile of frequent transit,” the commission wrote in a comment letter last December. “Reducing these requirements will allow for broader development of this building type in more neighborhoods throughout the city.”

While the delay of the overall Comprehensive Plan will push any discussion of allowing larger apartment buildings in new neighborhood centers and near transit into the future, the debate over how to legalize middle housing in Seattle isn’t likely to be any less contentious. And because it’s an interim ordinance, the council will have to go back and make it permanent later, creating the potential for some of these fights to be reignited a second time.

Update: This article was updated at 3:40pm to note that Dan Strauss has been removed as vice chair of the select committee.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.