Today, Transit Riders Union General Secretary Katie Wilson jumped in the race to be the next mayor of Seattle, challenging incumbent Bruce Harrell. A leader of numerous local progressive coalitions, Wilson was one of the key architects of the JumpStart Seattle progressive payroll tax, which saved the City from deep cuts amidst the recession and boosted affordable housing investment. She pointed to wins like JumpStart and her coalition-building experience more broadly as her reason for launching a campaign.

“I love this city, and I think we can do better,” Wilson said. “I’ve spent the last 14 years of my career organizing and winning victories that put money in the pockets of working families, everything from higher wages to stronger renter protections and affordable and accessible public transit. And I want to bring that experience into into City Hall. I have 14 years of experience in building and leading powerful coalitions, and in that time, I’ve learned how City Hall works, and I’ve learned how it often fails to work for the people of the city.”

Despite running an outsider campaign in 2021, Harrell is the ultimate insider, Wilson argued, and bears considerable responsibility for key city failures over the past two decades. Harrell and the Seattle City Council raided JumpStart revenue, which was mostly set aside for affordable housing, to fund their new priorities last budget season, which included a 16% boost to the police department budget, which is still a smaller force than when Harrell took office.

“[W]e need leadership that is prepared to tackle the major challenges that our city faces with energy and thoughtfulness, and Harrell, the incumbent, has been a politician in City Hall for 16 out of the last 18 years,” Wilson said. “We’ve seen many of the problems our city faces getting worse over that time, and I think we can do better.”

Wilson does not own a car and has long advocated for more frequent and accessible transit, renter protections, and abundant housing. Until she had her daughter, Wilson said she primarily biked to get around, and now she said transit is her top means of transport, though she also borrows a car from friends when the need arises.

I won’t pretend to be an outside observer. I’ve known Katie and advocated alongside for the better part of a decade. She has freelanced for The Urbanist, contributing op-eds including a Policy Lab series highlighting best practices from around the country. I’ve seen her lead coalitions to major wins that didn’t seem possible at first. Together we co-founded the Move All Seattle Sustainably (MASS) Coalition in 2018 after seeing that the City wasn’t doing enough to prepare for the Alaskan Way Viaduct demolition, which pushed the city to add bus lanes and bike lanes — though of course not as many as we asked for. I’ve watched her raise her young daughter Josephine, bringing her to political rallies and meetings, feeding her and entertaining her between a speech or deliberations without missing a beat. This is someone who has lived and breathed advocacy for urbanism, transit, and economic justice over the past decade.

Housing needs and a path for progressive leadership

Despite pundit efforts to paint a second Harrell term as inevitable given his 17-point victory in 2021, Wilson sees an opening for a real progressive leader to step in.

“We need city leadership that’s going to step up and work for the people of the city and not for their corporate backers,” Wilson said. “And I think we just saw with the social housing vote on Prop 1A how out of step Harrell is with the voters. He chose to be the face of the opposition campaign that was funded by Amazon and the Chamber of Commerce. Seattle voters overwhelmingly said that they want to see bold action on affordable housing, and so do I. So that’s why I’m running.”

Wilson pointed out how the issue of housing connects with her personal story of moving to Seattle with big dreams but a fairly empty bank account. She worries that the door is closing to the next generation who want to build a life in Seattle even if they’re starting with next to nothing.

“I moved to Seattle over 20 years ago now, and when my husband and I arrived here, we didn’t have jobs; we didn’t have a lot of money in the bank,” Wilson said. “We were able to find an affordable place to live. And I cannot imagine how hard it must be today for young people moving to this city who don’t have a tech job lined up or whatever, to build a life here. So I when I think about the Seattle that I want to live in, I want it to be a place where other young couples can move and build their lives, and I want it to be a place where my daughter can grow up and afford to live. And so stepping up our funding for publicly owned affordable housing is a big part of that. But there are other pieces too, and one of those pieces is implementing the Comprehensive Plan as ambitiously as we can.”

TRU pushed the City to go big on the Comprehensive Plan early in the scoping phase, when the group joined the push to add Alternative 6 to the city’s study, which would have gone beyond the City’s boldest alternatives to add more housing in every neighborhood and create larger incentives for traditional affordable housing and for social housing. The Harrell Administration ultimately refused to study the option, but housing advocates did push the City to boost Alternative 5 and make the middle housing zoning more generous.

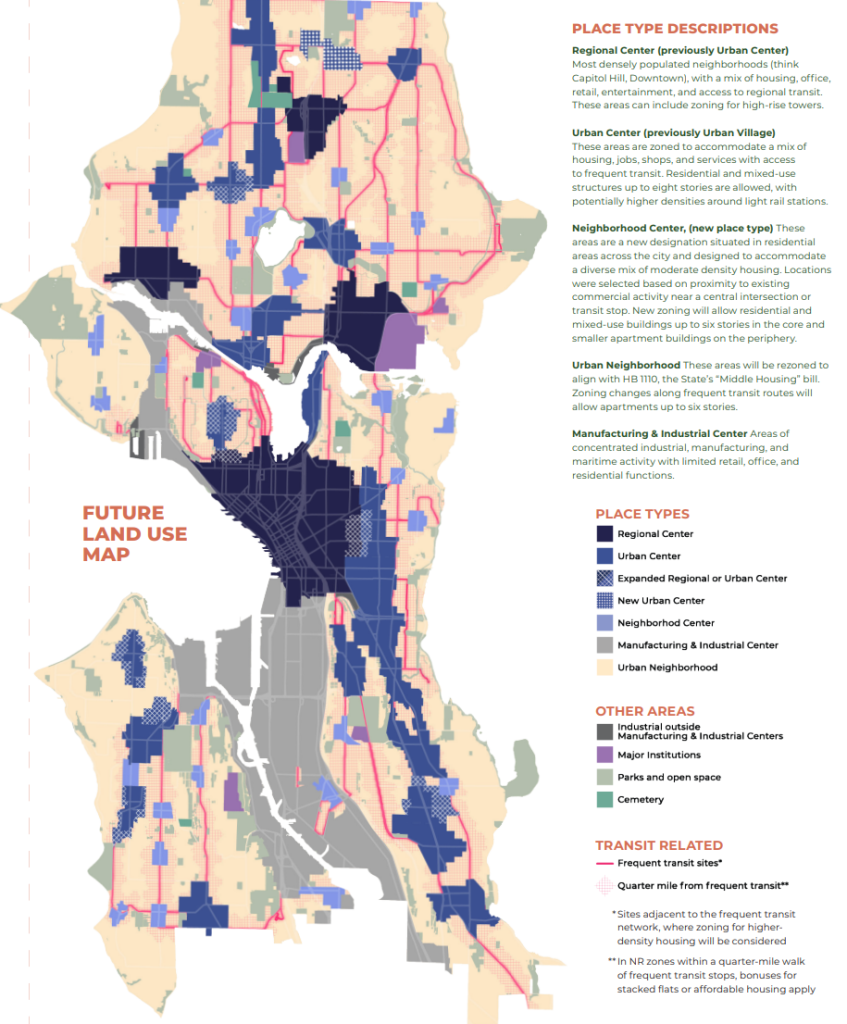

One area where the mayor didn’t really budge is citywide transit-oriented development. Under his plan, upzones to allow midrise apartments would only happen on the block immediately next to major bus lines, which are frequently on busy arterial roads — not also on the quieter side streets that housing advocates explicitly requested. Advocates argued those local streets farther off the arterial were safer, less polluted, and more desirable places to live, especially for families with kids. This ‘apartments go on arterials’ pattern is apparent in the thin red lines in Harrell’s proposed zoning map below.

“We need more housing pretty much all over the city, and especially in great neighborhoods that already have good schools and parks and small businesses,” Wilson said. “We need a lot more multi family housing near transit. We need, ideally, a bigger definition of what near transit means than is currently being considered, and I think we need more family-sized housing as well. And here I’m speaking as someone who has a young daughter, and the jump in price, for example, from a one bedroom to a two-bedroom apartment or a three-bedroom apartment is pretty unacceptable. So yeah, I would want to make sure that we’re building a lot of housing everywhere.”

While Harrell’s housing plan has focused on townhome development, Wilson pointed to Spokane-style sixplex stacked flats as overlooked and something that the City should be encouraging. Disability Rights Washington’s Cecilia Black recently laid out how the City’s plan can create more housing for people with disabilities, noting stacked flats are much more accessible compared to stair-heavy townhomes.

Theoretically, the Comprehensive Plan should be done by next year — in fact it was due at the end of the last year and faces a key state deadline on July 1. However, legal appeals from anti-housing groups and a decision to segment the plan into multiple phases means the plan might be getting cleaned up and finalized in the next mayoral term.

Staunch support for social housing

Harrell’s efforts to sabotage the Seattle Social Housing Developer go beyond his aggressive opposition to Proposition 1A, Wilson argued. Prop 1A passed by a 26-point margin and set a turnout record for a February special election (which are normally very low turnout) despite Harrell endorsing the Council’s alternative Prop 1B and appearing on mailers seeking to sap support from 1A.

“I think it’s clear that Harrell’s administration is not a supporter of the new social housing developer, even though voters overwhelmingly voted to establish it, and now, most recently, to fund it,” Wilson said. “There are things that a mayor who supported the developer could be doing right now to make sure that it gets off on a good footing.”

Hardly a friendly alternative, Prop 1B would have sunset after five years and allocated a much smaller amount of funding (again raided from JumpStart) instead of adding a new dedicated revenue source via a high earners tax on the city’s wealthiest companies. Email records show the Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce crafted Prop 1B in hopes of blocking the tax and pressured the Seattle City Council to delay the vote to February and put the competing measure on the ballot.

Wilson said she would be much more focused on timely collaboration with the Social Housing Developer rather than the neglect and obstacle-throwing that seemed to have characterized the City’s approach so far.

“Harrell has slow rolled initial funding that was allocated to the social housing developer, and he could have proposed a Comprehensive Plan that would have given the same density bonuses to social housing as it did to other types of affordable housing,” Wilson said. “He did not, and maybe he’ll do this soon. The mayor is supposed to be appointing a public finance expert to the social housing developer board, and that also has not happened yet.”

A renter protections push could also be in the cards under a Mayor Wilson.

“We live in a city that is majority renter, and it’s a growing majority that rents in our city,” Wilson said. “I think we’re seeing some pretty bad behavior, especially by corporate landlords. I’ve written about some of these ideas for The Urbanist — but I would want to look at how we can crack down on rental junk fees, on algorithmic price fixing, and on deceptive practices, again, especially by corporate landlords. Those are things that I think could have a significant impact for renters.”

Transit and safe streets

With her background in transit advocacy, Wilson would lead with eye toward expanding transit service and ensuring mobility is affordable to all. That has been her record at TRU.

“I co-founded the Transit Riders Union, which has grown into a multi-issue economic justice organization,” Wilson said. “We began organizing around issues related to public transit, and this was after the Great Recession decimated public transit budgets around the country, and so King County Metro was facing a prospect of deep service cuts, and had increased fares several times over the space of a few years. Me and my husband and some other folks we knew ran a campaign to rally the public to try to save bus service. And out of that grew the Transit Riders Union, and some of our first work was focused on transit affordability.”

Organized as an “independent, democratic, member-run union of transit riders organizing for better public transit,” TRU was able to mobilize transit advocates for considerable wins.

“We built a coalition that won the Orca LIFT low income fare program, which now serves tens of thousands, if not more, riders around our region, allowing people in low incomes to ride for cheaper,” Wilson said. “And over the years, we’ve played a big role in winning a number of reduced- and free-fare programs, including the Seattle youth Orca program that eventually inspired the statewide free transit for youth and human services bus ticket program and the subsidized annual pass program, and basically trying to make sure that everyone in our community has the mobility that they need to get where they need to go.”

In addition to fighting to make transit cheaper to ride, TRU has also fought to boost funding so that service frequencies can increase and Metro can add enhanced bus routes.

“We’ve also, over the years, fought for more funding for public transit,” Wilson said. “Despite the challenges, many of which were brought on by the pandemic, we have a great transit system that we can be proud of here, and we’re always going to be fighting to make it better.”

Wilson pointed to the 2026 renewal of the Seattle Transit Measure as an opportunity to expand bus service and potentially take a regional approach to augmented bus service.

“We’re looking ahead to 2026 right, the Seattle Transportation Benefit District will be up for renewal, which is kind of insane to think about,” Wilson said. “It’s like, we just just passed in 2020. Time goes fast. I think that there’s both an opportunity and a challenge there. Because I think we would all like to see a more regional measure that is increasing transit service all over King County.”

A regional approach could help improve service in other transit reliant parts of the metropolitan area, such as South King County. With a trend toward suburbanizing poverty, more transit riders are getting pushed out of Seattle and the inner suburbs and forced into longer commutes.

“We know that we have people who work in this city who can’t afford to live here, and who are commuting by public transit or by car, a long way from elsewhere, especially in South King County, sometimes even beyond King County,” Wilson said. “And we need more transit options. We need fast, frequent, reliable public transit all over the county. So I would want to work really closely with King County leadership, with the transit agencies and figure out: Is there a way to thread that needle? Is there a way to get to a regional transit measure in the near future, as opposed to just Seattle going in alone again?”

Wilson expressed interest in reviving study of de-congestion-focused road pricing that Mayor Jenny Durkan floated then abandoned in her term, pivoting to other less-effective climate action and mobility strategies. Durkan boasted Seattle might leapfrog New York in implementing a program. That didn’t happen and Manhattan finally rolled out its program in January, which appears to be a hit with New Yorkers as traffic has eased.

“Now that we have a city in the U.S. that is doing congestion pricing, I think that is very illuminating and instructive to look at the way that that’s going in New York City,” Wilson said. “Because it kind of has followed the path that I understand congestion pricing has taken in a lot of other places, which is people hate it until they get it. I would definitely want to, like at least, be developing some scenarios for how we could do something like that here, because that’s really a potential robust funding source for transportation improvements and public transit and something which could be really successful if we can find a way to do it equitably here.”

Wilson also vowed support for pedestrianizing more streets in the city, including Pike Place, which the Mayor backed in his annual “State of the City” speech last month, but which he wasn’t able to accomplish in his first term. She acknowledged that vendor and small business owners need to be engaged and brought along, but that there’s a way forward.

“There’s ways that we can try things out,” Wilson said. “We can do pilots and and see how things work, and hopefully ease people into a situation where they can see, just like, what a difference it makes. Because if you travel to other cities that have these wonderful pedestrian plazas and places where you can sit outside and eat, it’s just, it’s magical. And we should have that here, right?”

Wilson endorsed safety overhauls of crash-prone streets like Rainier and Aurora Avenue, saying it’s taken the City too long to get it done. Harrell’s recent speech also announced a new Aurora effort, though the road safety component is ill-defined at this point.

“We have corridors in our city where we just continue to have traffic fatalities and pedestrian deaths, and Rainier Avenue is one of those corridors that was Harrell’s district, and I wish over the years that he had done more to push for street safety measures on Rainier,” Wilson said. “Aurora Avenue is obviously another one. We need to make progress toward Vision Zero. We can’t keep having people die in the streets.”

Wilson has also been a leader on improving transit safety. The Amalgamated Transit Union invited her to speak at the memorial service for Shawn Yim, the bus operator slain in the line of duty in December. Wilson pledged support for ATU’s plan to convene local leaders and mobilize them action to improve safety both in buses and stops and regionwide.

Economic justice and coalition approach

TRU has branched out and focused on economic justice issues, particularly since the pandemic hit.

“[I] have expanded our work to take on other issues,” Wilson said. “We’ve led on raising the minimum wage in several jurisdictions around King County. We’ve built a coalition and led the charge for stronger renter protections in Seattle and many cities around King County, and also played a key role in winning the the JumpStart Payroll Expense Tax, which was passed in 2020 and which was basically responsible for the fact that we didn’t have truly devastating cuts, both during the pandemic and in the last last year’s budget process.”

While he did serve as a Seattle councilmember for 12 years, Harrell was not in office when JumpStart passed. Nonetheless, Harrell hasn’t been shy about siphoning funding away from the program, which was designed to allocate two-thirds of revenue its total on affordable housing and City’s Equitable Development Initiative.

“Coincidentally, the year that [JumpStart] was passed was one of the only two years in the last 18 that Harrell wasn’t in office,” Wilson said. “So, you know, you’re welcome, Mayor Harrell.”

The coalition work she’s led with TRU is great preparation for being mayor, Wilson said.

“That’s been my role, really, is bringing people together, bringing together individuals with expertise, with skills, bringing together organizations, and making big things happen,” Wilson said. “That is the skillset that a mayor needs, right? That’s kind of what leadership is, right? It’s assembling a team of people who have the competence and providing the vision and making sure that everyone’s pulling together and doing their part. And that’s what I’ve been doing for the last 14 years.”

While Wilson has navigated many a stakeholder process, she underscored that outreach processes are a means to an end, not something to get bogged down in endlessly or treat as progress simply for kicking tires and floating ideas.

“The kind of stakeholder process that I do, like we get results, right? We’re not just getting together in a room to chitchat and put sticky notes on a wall,” Wilson said. “We’re trying to get stuff done. And that’s the kind of energy that I would want to bring to the mayor’s office.”

Safety, civilian response, and dealing with SPOG

Wilson was critical of how Harrell has approached public safety. She pointed out the police contract that Harrell negotiated with the Seattle Police Officers Guild (SPOG) failed to add accountability measures or ensure that civilian crisis response programs could expand as needed. The new contract stipulates that the Community Assisted Response & Engagement (CARE) is capped at 24 responders — which is less than 3% of the size of the police force.

“We saw the mayor negotiate the most recent SPOG contract, and I don’t think he did a good job. Let’s just put it that way,” Wilson said. “There was such a mad rush to give the police like the maximum pay, and I’m not saying that that didn’t need to be where it ended up, but that they didn’t leave themselves any negotiating room to get anything in return. That’s kind of the one bargaining chip that the City has… We should have gotten way more accountability measures, and most importantly, in my point of view, greater capacity for alternative response, because it’s part of the reason why police response time is so bad right now. If you’re in a dangerous situation or you’re the victim of a crime, and you call the police, it’s reasonable to expect that they’re going to arrive in a timely manner.”

The mayor has also let the police department control which calls that the CARE department responds to and require a police officer to accompany them as part of a “dual-responder model” that critics have criticized as cumbersome and not freeing up police to respond to more urgent calls.

“Part of the reason why that situation exists is that we have police doing so many jobs and responding to so many calls for which they’re not necessary or not even a good response,” Wilson said. “We have the CARE department that is doing some alternative response, but the police contract limits how much that can be scaled up.”

Harrell ran for mayor pledging to institute culture change at SPD. One idea he floated (and never implemented) was requiring every police officer watch the whole nine-minute video of George Floyd being strangled to death by a Minneapolis police officer. When it has come to actually workable culture change ideas, it’s been a mixed bag, with Harrell now on his third police chief in three years and change after he finally ousted his first pick, Adrian Diaz, amid numerous scandals and costly lawsuits.

“Culture change is hard, and we need to do it,” Wilson said. “Part of that is definitely good leadership. We’ve seen some, I would say, charitably poor judgment calls from Harrell in leadership appointments. We’ve had him appoint a police chief who was and caused multiple lawsuits. That’s poor judgment. I think that’s a very important piece of the puzzle.”

Visit wilsonforseattle.com for more information and opportunities to get involved.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.