When Cheyne Clark became paralyzed last May, he knew he couldn’t continue to live in the two-story rental he shared with three friends. Searching on Zillow, he turned on the filter for accessible housing and watched his prospects go from 200 units to zero. The majority of accessible housing within his price range was far from the city, but he knew that he needed to live where he could easily access community and friends in order to recover mentally and physically as he adjusted to life with a disability.

In the end, Cheyne got lucky and found a roommate to be able to afford an apartment in Ballard, but his rental search highlights an unjust reality in Seattle: there’s a severe lack of accessible housing and vast swaths of the city have essentially zero accessible units.

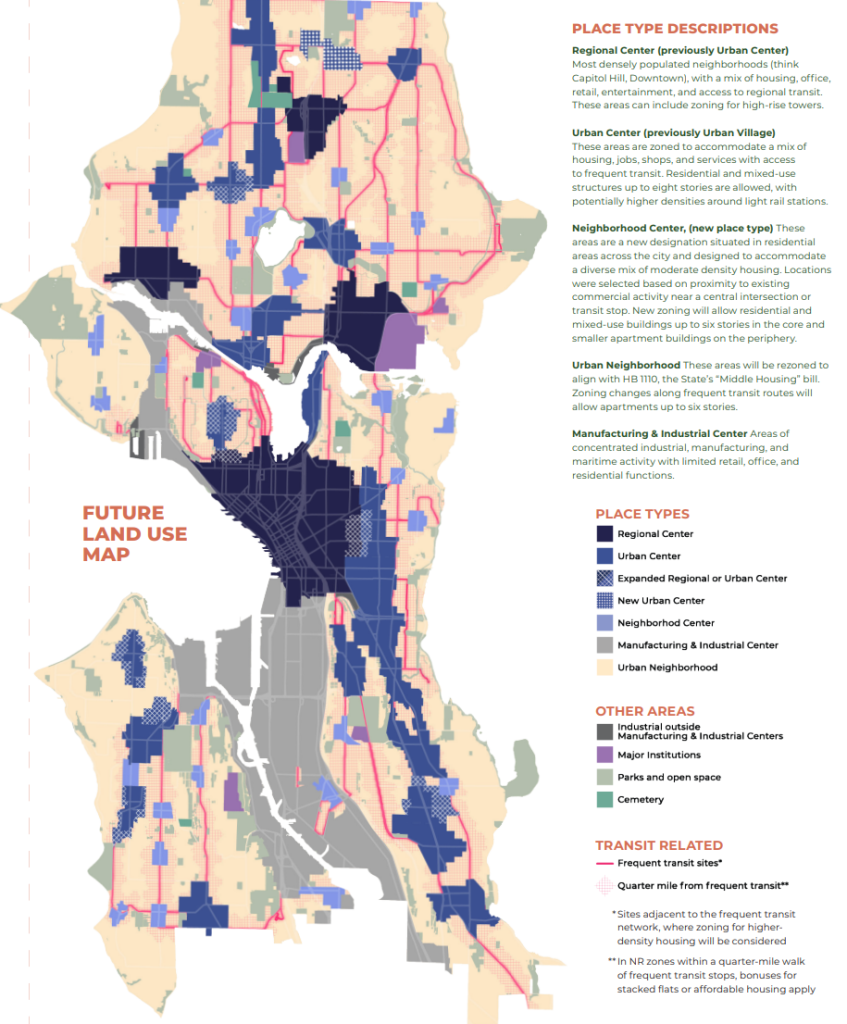

Unfortunately, this problem isn’t an accident, but rather a specific feature of our city’s planning codes. For the last 30 years, Seattle has adopted an urban village approach to growth that has reserved 75% of the city for single-family zoning while concentrating growth into walkable urban centers. This has created a de-facto form of housing segregation, where people with disabilities can essentially only reside inside the minority of neighborhoods classified as urban centers.

Federal and state housing laws enforce accessibility standards for multi-family housing with four or more units, with the strongest requirements on buildings with 10 or more units to build wheelchair accessible units. Single family homes face no requirements to be accessible. Combined with our dominance of single-family zoning, this means that the majority of our city prohibits the types of housing most likely to be accessible, leaving many neighborhoods with very few options for people with mobility disabilities.

Single-family-zoned neighborhoods also limit accessibility by requiring residents to drive to access businesses, services, and transit. We usually talk about walkability as an environmental and community benefit. But for nondrivers and people with disabilities, it is a lifeline.

As Tanisha Sepúlveda, a Seattle powerchair user, explains: “Accessible housing is bigger than how a building is built, or an apartment is laid out.” For Tanisha and the many people with disabilities like her who cannot drive, accessibility means living within walking and rolling distance of resources or public transit that can get you where you need to go.

Accessible housing: Too rare and expensive

Meanwhile, Seattle’s urban villages have grown denser with more accessible housing and walkable neighborhoods, a clear benefit Seattle should be proud of. Yet by squeezing these accessible neighborhoods into a tiny minority of the city, Seattle has limited the supply of accessible spaces and made them extremely expensive. This disproportionately affects people with disabilities, who are more than twice as likely to live in poverty. As a result, our neighborhoods with the most transportation and housing options are often out of reach for the people facing the greatest housing and transportation barriers.

This isn’t just a problem for people with physical disabilities. I have attended several comprehensive plan community events over the past year and listened to older homeowners talk about how they, understandably, plan to stay in their homes. Every time I wonder if they are prepared for the inevitability of aging into disability.

My family certainly wasn’t prepared when I suddenly became paralyzed in high school. Our house wasn’t remotely accessible. My parents scrambled to find housing so that I could come home from the hospital and were faced with the harsh reality that wheelchair- accessible houses are simply not available.

Nineteen percent of U.S. households have one member with a mobility disability — yet nationwide less than 5% of housing is accessible and less than 1% of that is wheelchair accessible.

In Seattle accessible units can be extremely hard to find. It took me eight months of calling dozens of buildings before I found a wheelchair accessible apartment. My one requisite: it needed to be within easy (for me) walking distance from a transit hub and at least one basic service, like a grocery store.

Finally, I found a brand-new apartment two blocks from the Roosevelt light rail station. I could walk to the grocery, grab a coffee, or hop on a bus or light rail without using all my energy just trying to get there. Living in a world not built for you is exhausting and I can’t fully explain the relief when leaving your house is just easy. This ease of access has been life changing.

In the context of Seattle land use and zoning, it’s not surprising I ended up in the Roosevelt neighborhood. Zoning changes in 2012 and development plans around the new light rail station paved the way for transit-oriented development, greater density, and mixed-use developments. Roosevelt has added 2,300 housing units to the neighborhood in the last 10 years, almost all of it in the form of new apartment buildings. New residents have increased demand for retail and other services, which are now expanding beyond the main commercial block, resulting in more access each added year.

Roosevelt represents the potential of new zoning changes. It’s clear Seattle can build vibrant accessible neighborhoods. But with limited growth opportunities this will continue to come with a price tag. The average rent for a Roosevelt apartment is $2,081. In order to afford to live in Roosevelt and not be rent burdened, you would need to earn about $75,000 a year.

Zone for accessibility to truly create One Seattle

Luckily, we can change this.

This year Seattle will adopt its updated comprehensive plan for the next 20 years. It will set the baseline for how neighborhoods can change and grow. In the next 20 years, Seattle’s 65 + population is projected to grow by 75%. At least 30% of Seattleites are nondrivers, and 1 in 3 renter households in Seattle don’t own a car. And we have a housing crisis that has been catastrophic for the disability community, with over half of people experiencing homelessness having at least one disability.

The current proposal fails to make Seattle more accessible.

Forty percent of the added development capacity under the current proposal is in urban neighborhoods with zoning that prohibits the multifamily developments that are most likely to be accessible and creates challenges for accessible housing options like stacked flats. The proposal adds the bulk of new potential multifamily development along busy corridors without the option for retail and commercial space.

At the center of the comprehensive plan debate is the city’s proposal to create “complete communities,” each spanning only a handful of blocks, in just 30 neighborhoods. In these hotly contested neighborhood centers, the city has laid out a vision for walkable neighborhoods with a mix of housing options and goods and services to walk to. We cannot lose these neighborhood centers. But if we are going to address accessibility, we need to take a bigger step away from single-family zoning and start envisioning a city where every person has an opportunity to live in a complete community.

As Council finalizes the comprehensive plan over the next several months, let’s embrace the moment to create a different city with accessible, multi-generational communities that support active mobility for people of all ages and abilities in every neighborhood.

Make your voice heard

The Seattle City Council’s Select Committee on the Comprehensive Plan will deliberate on amendments in coming weeks — though the legal appeal by neighborhood groups could delay the full package of legislation. Email your Seattle councilmembers at council@seattle.gov and visit OneSeattleForAll.org and Complete Communities Coalition for opportunities to engage.

Cecilia Black

Cecelia Black (she/her) is a wheelchair user and community organizer at Disability Rights Washington, where she works with nondrivers and people with disabilities to fight for transportation justice. Outside of DRW, Cecelia is a member of Sound Transit's Citizens Accessibility Advisory Committee, Seattle's Planning Commission, and Be:Seattle’s Board of Directors.