The Washington State Legislature is starting to reckon with a massive budget hole in the state transportation budget, and some of the state’s most prioritized highway widening and expansion projects could be put in the crosshairs. As the days start to tick down toward the end of the legislative session on April 27, different options are starting to emerge around how lawmakers might start to make up a nearly $8 billion budget gap over the next six years. Few areas of the budget are fully safe from cuts, and a way forward to closing the gap is unlikely without delaying, or even cancelling, some long-planned highway expansion projects.

For years, policy experts at the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT), including Roger Millar, its most recent secretary, have been recommending that the state shift spending away from highway expansion projects, arguing that basic maintenance and preservation work is getting neglected along with urgent safety work. Millar also argued that creating new traffic capacity in the name of reducing congestion is a fool’s errand.

In contrast, the state legislature has tried to downplay its focus on highway expansion, even as the state’s maintenance backlog continues to grow. In doing so, lawmakers have largely been ignoring the detrimental impact that highway expansion projects have on the state’s climate goals.

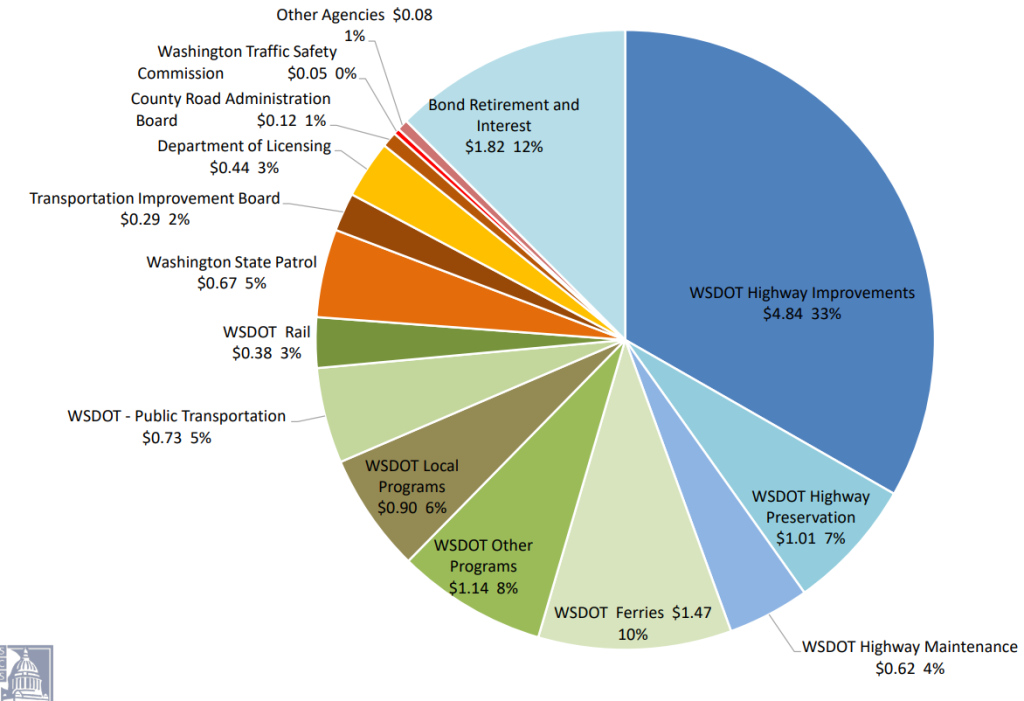

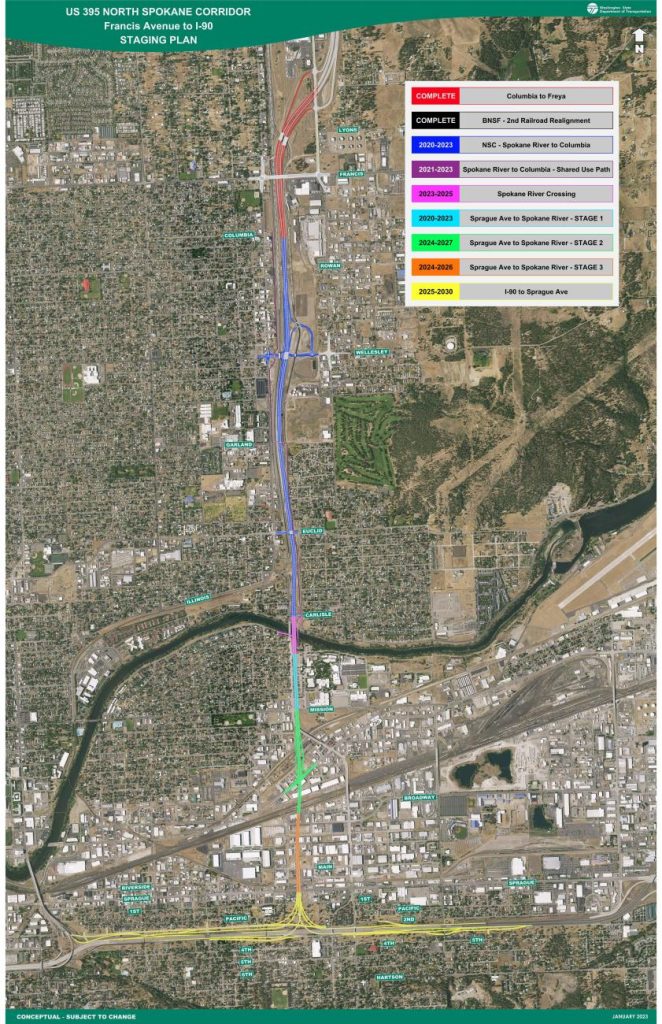

Highway “improvements” are the single biggest expenditure in Washington’s transportation budget, which is separate from the state’s operating and capital budgets, though some funding sources do overlap. The operating budget also faces a significant budget hole, but the transportation’s budget issues are much more systemic, with any real fixes likely to take years to implement. The biggest projects in the highway improvement budget, apart from court-ordered fish passage projects, are long-term highway megaprojects, like the North Spokane Corridor, the Puget Sound Gateway, and Interstate Bridge Replacement, which would widen I-5 in in Clark County.

Cost increases on projects like these are a major factor behind the massive budget crunch, along with declining gas tax revenue. Combined together, cost increases on just four projects — the North Spokane Corridor, I-405 widening, I-90 widening at Snoqualmie Pass, and the Puget Sound Gateway program — total $785 million, though those totals would be spread over several biennial budgets, so it’s not as simple as putting those four projects alone on hold.

Last week, the House and Senate transportation committees were shown three potential pathways to closing the budget gap, which totals $1 billion for the next two year budget covering 2025-2027. One option looked at potential cuts to the state’s transportation operating budgets, which fund staff and day-to-day operations. Filling the gap there would require 25% cuts across all of the state’s transportation agencies: ferries, highways, public transportation, Washington State Patrol, and the Department of Licensing. The budget gap is so large that not even eliminating the entire operating budget for Washington State Ferries would be enough to close it.

By contrast, delaying contracts on the highway “improvement” projects that haven’t yet been awarded — excluding fish passage, preservation, and safety projects — would yield more than $1.1 billion in savings over the 2025-2027 biennium and more than $3.5 billion over six years. Along with the projects mentioned, the top ten list includes the widening of State Route 18 in southeast King County, an expanded US 2 trestle in Snohomish County, and an expanded State Route 3 in Kitsap County near Gorst.

The Interstate Bridge Replacement, the planned expansion of I-5 between Washington and Oregon that is poised to be the most expensive transportation project in Pacific Northwest history, is currently being treated separately, likely because of the extra layer of bistate coordination that comes with it. But Oregon is facing a similar budget crunch, with a $1 billion budget error by the Oregon Department of Transportation revealed last month adding an extra layer of complications. Making matters worse, federal transit funding for light rail on the corridor seems likely to disappear — at least for the duration of the Trump Administration.

And then there’s door number three: raising revenue. With Democrats in the legislature exploring broader revenue options to plug the hole in the operating budget, most of the options being considered for the transportation budget are transportation-related. Those include a potential gas tax increase, additional fees on passenger vehicles and freight trucks, driver’s license fee increases, and ferry fare hikes.

In 2022, when the legislature passed the last major transportation package, Move Ahead Washington, the fact that a gas tax increase wasn’t included was a major talking point, but few other available options would produce the amount of revenue necessary to save some of these prized highway projects. An 8.7 cent gas tax increase would produce about $500 million per biennium, the same amount as all of the other options under consideration combined. And so the legislature is being faced with a choice: raise the gas tax or defer many of those projects.

Governor Bob Ferguson, who has issued a slate of recommendations to help close the operating budget gap, has not yet weighed in with any recommendations to close the giant hole in the transportation budget. In a press conference Thursday, Ferguson painted major ferry cuts as off-limits, a move that would put the entire burden on the highway program. At the event, Ferguson announcing a plan to defer the long-planned conversion of two state ferry vessels to hybrid electric propulsion systems, setting a goal of fully restoring pre-pandemic ferry service by this summer.

“We will not be successful in where we need to go as a ferry system if we do not have the staff adequately compensated to help run that operation,” Ferguson told The Urbanist. “This is not the time to back away from the system, it’s the time to lean into the system, to lean into those investments, or we’re going to create additional problems down the road.”

The legislature is also considering some potentially significant cuts to the state’s bicycle, pedestrian, and safe routes to school programs, cuts that would be particularly devastating at a time when the federal government is likely to put the same types of programs on the chopping block. But potential savings from those programs pale in comparison to the highway projects: putting the entire bicycle and pedestrian safety grant program and the entire safe routes to school program on hold for two years would save the same amount as postponing one highway project, a widening of SR 9 in Snohomish County.

Most of the work to hash out budget proposals in both the House and the Senate is happening away from public view, with select legislators picked to join a transportation budget “cabinet” that will eventually lead to a draft budget that will be released in late March, with a Senate budget coming out first.

While delaying projects may free up the funds that legislators need to be able to fill the budget gap, it doesn’t address another major issue facing the state’s transportation system: an underinvestment in basic maintenance. Without a full reprioritization that looks at whether a focus on capacity projects is truly aligned with state goals, the legislature is likely to end up back at the same place within a few years.

While Julie Meredith, Washington’s new transportation secretary, is poised to take a more subdued approach in comparison to her predecessor, she does seem to be in agreement with Millar that the legislature needs to shift its thinking.

“Over the last 25 years, I’ve worked on capital delivery, and you’ll hear me say, we’re really fortunate to have worked on $16 billion of infrastructure, really important infrastructure, but that same level of investment has not been made in our maintenance and preservation program,” Meredith said last week at a meeting of the Puget Sound Regional Council. “We need to invest in our maintenance and preservation and it has been something that hasn’t been invested in, to keep up to a state of good repair.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.