Entering a police department that has been dogged by scandals for more than a decade, new Seattle Police Department (SPD) Chief Shon Barnes has the luxury of an outsider’s perspective. At the Seattle City Council’s Public Safety Committee meeting last Tuesday, he spoke with an optimism that Seattle has not heard in some time.

“We should see our police department return to normal,” Barnes told councilmembers.

His last two predecessors as permanent chiefs, Adrian Diaz and Carmen Best, both rose from within SPD ranks. Carmen Best didn’t make the original shortlist for SPD Chief back in 2018, but after criticism from community groups, including the city’s Community Police Commission, her name was added to the list, and she was eventually tapped for the job.

Best resigned two years later in the wake of the George Floyd protests and SPD’s abandonment of the East Precinct. A King County investigation later confirmed that she had deleted work-related text messages that were subject to the Public Records Act.

Diaz had an easier path to eventually being named police chief, but he lasted less than two years before Mayor Bruce Harrell asked him to step down amidst a steady stream of allegations of racial and sexual discrimination and harassment within SPD. Harrell eventually fired Diaz in December for lying about a relationship he had with his chief of staff, proof of which was provided by an Ewok-themed card found in Diaz’s car.

Barnes’s first day at SPD was Friday, January 31. He will serve as interim chief until he goes through the city council’s confirmation process.

Who is Shon Barnes?

Originally a history high school teacher, Barnes has been in law enforcement for 24 years, including his most recent stint as Chief of Police in Madison, Wisconsin since 2021 . Barnes rose to national prominence in December after a school shooting in Madison left three dead.

Barnes holds a Master of Science in Criminal Justice from the University of Cincinnati and a Ph.D. in Leadership Studies from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University. His dissertation topic was racial profiling in traffic stops, a subject that is relevant in Seattle, where consent decree data shows that SPD still stops and frisks Black and Indigenous people at much higher rates than White people.

When discussing Seattle’s expected exit from its lengthy consent decree, Barnes referenced his experience as one of two police officers who was an investigator on a pattern and practice case against the City of Minneapolis after the murder of George Floyd.

“I’m fully expecting that we will see the end of our consent decree this year,” Barnes said. “And then we will mark a new phase where we make sure that we’re actualizing all of these great recommendations that were made to make sure that we present the type of police department that our community deserves.”

In an interview with PubliCola, Barnes said he was the only chief in the United States who has also worked for civilian police oversight, so we can expect him to have opinions about Seattle’s much-vaunted accountability system, which has been prevented from working as designed due to the Seattle Police Officers Guild (SPOG) contract with the City. Lack of support from City Hall could also be emerging as an issue for the accountability bodies.

Barnes told Councilmember Rob Saka that he hadn’t yet officially met with Seattle’s three accountability bodies – the Office of Police Accountability, the Office of the Inspector General, and the Community Police Commission – but those meetings are on the calendar. Two of the three agencies currently have interim directors, which could lessen their weight.

New departmental priorities

Barnes presented his mission statement for SPD to the city council’s Public Safety Committee. “My personal vision is really simple: that the Seattle Police Department will aim to create a safe and supportive Seattle through our commitment to excellence, selfless public service, resilience, community partnerships, and continuous improvement,” Barnes said.

He covered his top five priorities for SPD: crime prevention, community partnerships, retention and recruitment of qualified workforce, employee safety and wellness, and continuous improvement.

He warned against “organizational exceptionalism,” the idea that an organization can’t do anything more to improve, citing a popular book: Why Law Enforcement Agencies Fail, by Patrick O’Hara. “People say, why would you read a book about failure?” Barnes said. “Because sometimes you can learn a lot from failure.”

Barnes spoke favorably of SPD’s new real-time crime center. “As you know, public space cameras are everywhere,” Barnes said, “and having the opportunity to access those in real time certainly decreases the amount of time it takes to find people and hold them accountable for whatever crime they may be a part of.”

Last year, the city council also signed off on city-owned CCTV cameras, which are expected to be installed soon in the 3rd Street corridor downtown, Aurora Avenue in North Seattle, and the Chinatown-International District (CID).

Barnes said he plans to change things up in SPD by adopting stratified policing, an initiative also mentioned by Harrell in his State of the City address earlier in February.

“We’ll be implementing stratified policing, which really takes what police departments do well, which is dividing work and assigning work, and making sure that we’re working together, that we’re breaking down silos, that we’re all looking at the community as a partner that’s going to include a lot of communication,” Barnes told councilmembers.

Stratified policing is a method Barnes used at the Madison Police Department (MPD). Documentation from MPD explains the basics of the method: “Stratified Policing provides a framework that clearly identifies the roles and responsibilities for all personnel in crime prevention and problem-oriented policing. Stratified policing uses crime analysis, problem solving, […] evidenced-based police practices, and a structure for organization-wide accountability.”

A presentation at the Problem-Oriented Policing Conference in the fall of 2024 in which Barnes participated called stratified policing “a business model for crime prevention” and touted significant decreases in robbery, burglary, theft from a motor vehicle, and motor vehicle theft in Madison. However, the official start of the stratified policing program in Madison was June 2, 2023, and numbers of the aforementioned crime categories had already begun trending downwards in 2022, so it is difficult to know how much of the change to credit to stratified policing specifically.

Philip V. McHarris, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Black Studies and Frederick Douglas Institute at the University of Rochester, does research focusing on racial inequality, housing, and policing. He has a different perspective on stratified policing.

“From what I’ve seen, it’s another iteration of “data-driven” and “problem-oriented” policing models that promise efficiency and accountability, but ultimately reinforce the same fundamental structures of surveillance and control — just with more layers of management and metrics,” McHarris told The Urbanist.

Critics also argue that stratified policing can distract from more promising solutions.

“The emphasis on organization-wide accountability may sound like reform, but in practice, it tends to expand police reach into communities rather than reduce harm or shift resources toward non-policing alternatives,” McHarris continued. “The question, then, is whether Seattle really needs a more structured police force — or if resources would be better spent on systems of care, crisis response, and community-led safety initiatives that don’t rely on law enforcement.”

SPD staffing

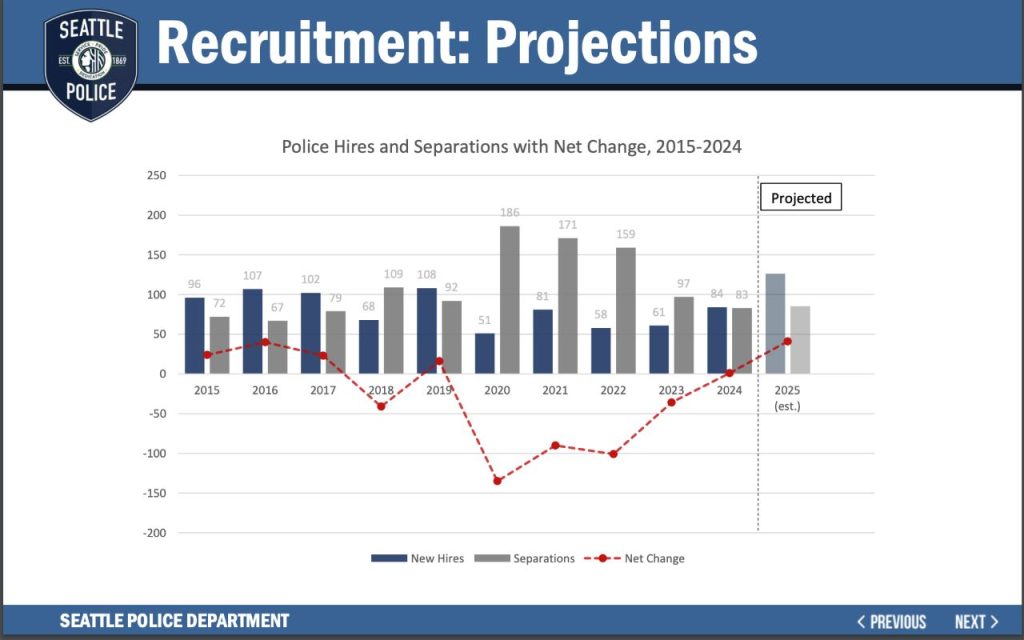

In 2024, SPD was able to hire one more police officer than they lost through attrition, the first time they’d seen a net gain in hiring since 2019.

The Seattle Times recently reported on SPD’s 2024 hires. Of the 84 new officer hires in 2024, only 15% of them were women, and more than 20% were ex-military. Nine (out of 11 total) lateral hires had previously worked for SPD, and at least seven of those were able to collect hiring bonuses from a different law enforcement agency before returning to SPD and collecting a second hiring bonus.

From their chart, SPD appears to be estimating they’ll be able to hire around 125 new officers this year, which would represent an increase of around 40 hires over last year. They estimate that departures will remain steady, which would lead to a net gain of around 42 officers.

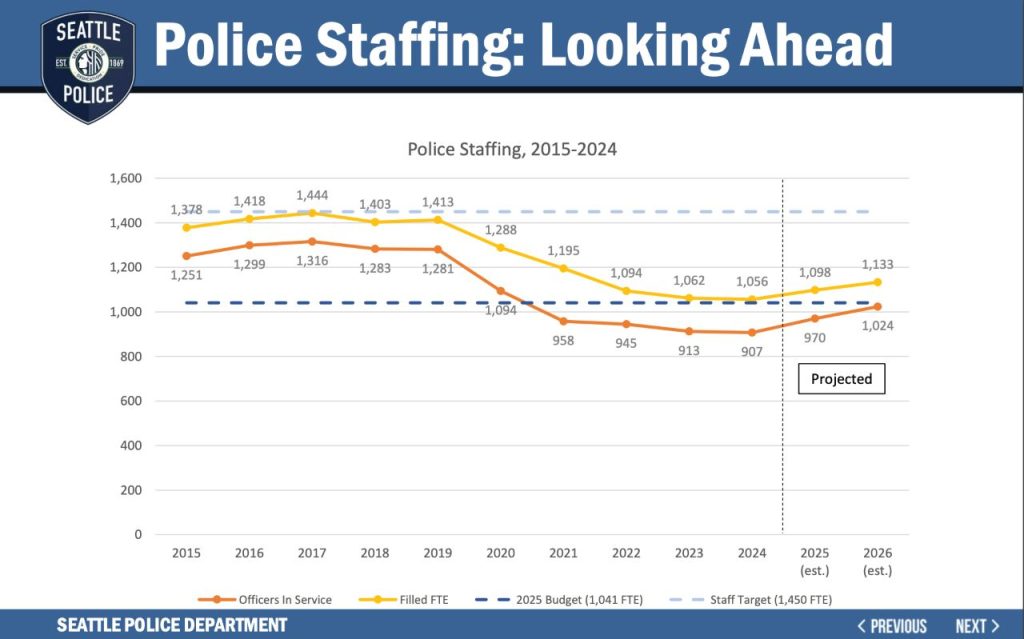

SPD had 907 officers in service in 2024. The department anticipates hitting 970 deployable officers by the end of this year and to 1,024 by the end of 2026 — though SPD has come up short on projections before as it has plotted its post-pandemic rebound.

The local landscape mirrors national trends of increased police staffing. Surveys from the Police Executive Research Forum show American law enforcement agencies began to show an increase in total officer staffing in 2023. At the time of the latest survey, large law enforcement agencies like SPD were still reporting staffing challenges compared to smaller agencies.

“The word is out that Seattle is a great place to work, a great place to come,” Barnes said.

Barnes is also eager to continue increasing SPD’s civilian staff, especially in investigations.

Barnes stated his continued support of the national 30×30 initiative, which he said has recently lost all its federal funding. The initiative has a goal of increasing women police officers to 30% of all officers by 2030. “Diverse groups outperform non-diverse groups when they’re managed well,” he told councilmembers.

Barnes discussed officer retention strategies, including officer safety and wellness, internal procedural justice, officer development and training, and capital improvements to police departments such as new carpet, new paint, and parking lot resurfacing.

Barnes also mentioned the SPOG contract as something officers have said is important for retention. SPD officers received an accumulated 24% raise in last year’s interim SPOG contract. While Barnes said he’s not “intimately involved” in the contract, it might prove to be one of the biggest obstacles to shifting the culture of the department.

Thus far SPOG has shown itself to be obstinately opposed to accepting accountability measures demanded by the community, as well as playing an active role in stymying the expansion of the Community Assisted Response and Engagement (CARE) alternative emergency response. These hardline stances have not necessarily earned SPD good will in the community SPD serves.

Still, Barnes remains positive about the work in front of him.

“I really see a department that is certainly poised to do great things. I think so much has been said about how many officers we don’t have, and not enough has been said about how many officers we do have, and because I know that we’re 300 short, I prefer to say we’re 900 strong,” Barnes said. “I think that the staff, they’re looking for direction. They want to know what they are accountable for, and they’re ready to deliver.”

Amy Sundberg is the publisher of Notes from the Emerald City, a weekly newsletter on Seattle politics and policy with a particular focus on public safety, police accountability, and the criminal legal system. She also writes science fiction, fantasy, and horror novels. She is particularly fond of Seattle’s parks, where she can often be found walking her little dog.