As part of his annual State of the City address last week, Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell announced that the city’s Office of the Waterfront and Civic Projects will be taking the lead on planning for Sound Transit 3 (ST3) projects within the city as part of a newly issued executive order. Harrell claimed the move will expedite delivery of the two major light rail extensions Sound Transit is planning within Seattle.

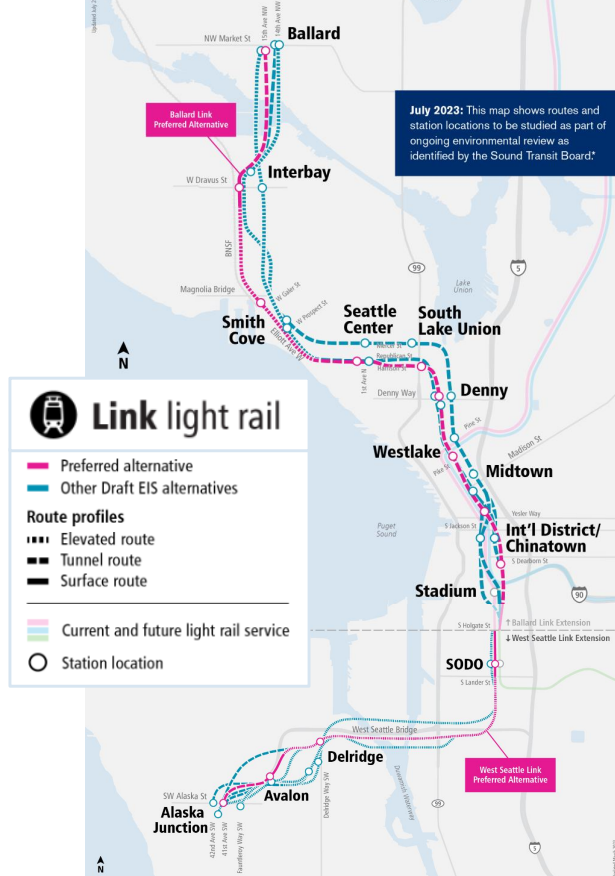

The restructure builds on moves that have previously been announced, including the planned expansion of the city’s ST3 team and a comprehensive land use code update intended to streamline permitting. Following years of planning snags and pandemic-related delays, the latest word from Sound Transit is that West Seattle Link would open in 2032 (two years later than pledged to voters) and Ballard Link in 2039 — four years later than advertised to voters.

In early February, Angela Brady, who has been the director of the Office of the Waterfront since 2022, was named the city’s “designated representative” for ST3 planning, a role that has existed since a partnering agreement between the City and Sound Transit was signed in 2017. Prior to this change, the role had been filled by Elliot Helmbrecht, a transportation policy advisor working directly out of Harrell’s office. That partnering agreement, signed by Mayor Jenny Durkan, pledged an ambitious timeline that included starting construction this year.

With ST3 planning moving entirely to the Office of the Waterfront, a department with a reputation for being opaque and inaccessible to the public will become a one-stop shop for permitting decisions related to the West Seattle and Ballard Link. Unlike the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT), which has a dedicated communications team dedicated to handling press requests and social media posts, the Office of the Waterfront has offloaded those responsibilities to a third-party consultant for years.

“Growing our transit network with fast, reliable service is one of my highest priorities, and Sound Transit 3 is the largest transit expansion in the country. That’s why, this week, I will issue an executive order to make sure the City of Seattle is taking immediate action to safely and efficiently expedite delivery of light rail to West Seattle and Ballard,” Harrell said in his speech. “Our efforts will include a newly expanded Office of Waterfront, Civic Projects and Sound Transit, led by Director Angela Brady, which will be at the center of orchestrating a surge in staff of up to 50 City employees supporting project design and engineering, station area planning, and more.”

With the expected opening of four-station West Seattle Link line already pushed back two years, and much more complicated nine-station Ballard Link four years behind its initial timeline, expediting delivery of these two megaprojects largely means delivering them on their current timelines, with actual acceleration much less likely.

The Sound Transit Board of Directors is moving full steam ahead on West Seattle Link. Last year, the agency approved station locations to advance into final design as part of the “project to be built,” even in the face of a 70% cost jump over earlier estimates. With the City of Seattle set to consider approximately 89 separate master-use permits as part of permitting just for West Seattle, the need to scale up the city’s internal team is apparent on the surface. But how this work will be made more efficient if it’s housed within the Office of the Waterfront is less clear.

“Sound Transit’s ST3 projects […] are transitioning from the planning and environmental review phases into massive scale design and construction efforts. The City needs to be poised to provide highly effective multi-departmental technical leadership to support these efforts,” the new executive order states. “The Office of Waterfront and Civic Projects has a demonstrated track record of successful partnership with other agencies and community stakeholders to deliver transformative major projects for the City of Seattle. The expanded Office of Waterfront, Civic Projects & Sound Transit is positioned to bring similar success and a One Seattle approach to other highly visible and complex projects like ST3.”

The Office of the Waterfront was created in 2014, with current Seattle Center Director Marshall Foster at the helm, in order to deliver and oversee the suite of projects associated with tearing down the Alaskan Way Viaduct and opening the SR 99 tunnel and Waterfront Park improvements that have come in its wake. Urbanists and safe streets advocates have criticized the department for not living up to pledges made earlier in the process, arguing the public has been misled by deceptive renderings and presentations.

One of the biggest opportunities to come with the waterfront project, a new north-south bike path, had long been presented as 12 feet wide, but after installation, it was found to be around three feet shorter in some segments, and curves in the path to accommodate space for on-street parking were rarely emphasized in graphics.

In another example of last-minute decision making happening beyond the public eye, project designs presented to the Seattle Design Commission showing bollards preventing drivers from accessing the waterfront bike path from the nearby Alaskan Way roadway were modified before being put out to bid, removing the bollards. That fact was only noticed during construction, years later.

Those critics have also raised concerns raised about the number of traffic lanes on a newly revamped waterfront, though those decisions were largely set by the Washington State Legislature as they debated the future of the State Route 99 corridor in the early 2010s

Brady has been with the Office of the Waterfront since its inception, taking the lead on critical design elements as the Deputy Director for Design and Delivery until taking the helm at the department in 2022 with Foster’s departure. Prior to that, she served as the project manager for another project lamented by many urbanists as another missed opportunity: the full rebuild of Mercer Street through South Lake Union, which opened in 2012.

Unlike with those projects, Sound Transit will remain in the driver’s seat when it comes to the major decisions that lie ahead for West Seattle and Ballard Link. While much of the work the expanded ST3 team will handle will be administrative, the City of Seattle will have a big role in deciding when to issue variances from its design standards for light rail stations, which were issued last year.

Those design standards — and how the planners under the Office of Waterfront umbrella interpret them — could have a big impact on things like the pedestrian experience at stations, and the integration of ST3 stations into the citywide bike and bus networks. They could also have an impact on project costs, with Sound Transit pledging to innovate with more standardized station designs.

Merging ST3 planning in with the Office of the Waterfront could be one of the most consequential decisions impacting transit in Seattle made in recent years, but just how consequential is something that likely won’t be known for many years, if not decades.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.