King County Metro continues to advance plans for the next RapidRide bus line on the Eastside, the K Line. As part of that project, the Bellevue City Council is starting to push for a change that could impact bus improvement projects across the state, allowing local cities to allow transit lanes to be used by private shuttle buses. Framed in Bellevue as a way to fully utilize the people-moving capabilities of transit facilities, the move could give transit agencies less control over one of their biggest tools to improve speed and reliability.

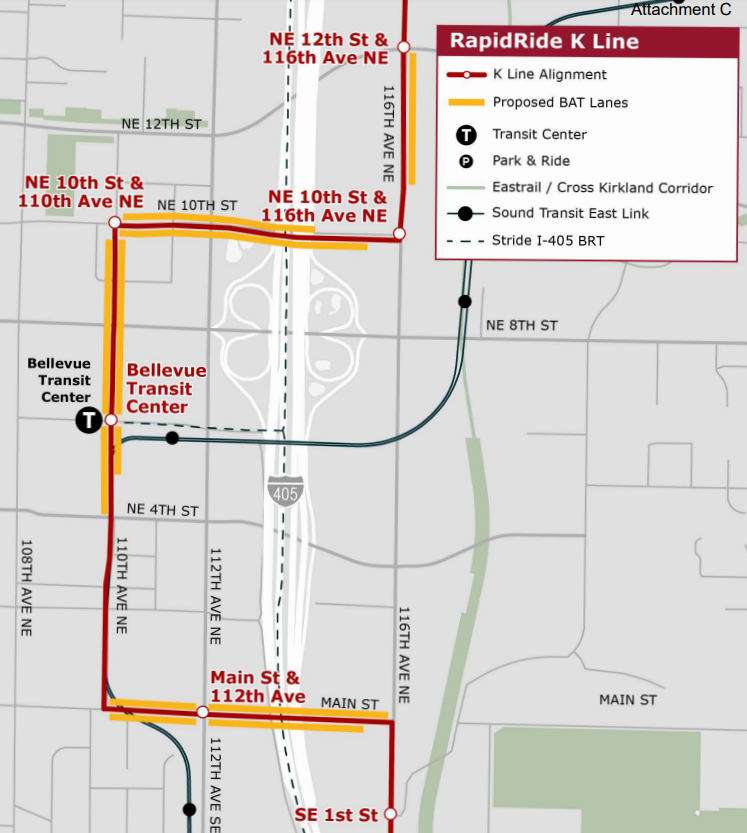

With the goal of providing faster and more reliable trips on the future K Line, Metro is proposing to add business access and transit (BAT) lanes in downtown Bellevue, including along NE 10th Street, 110th Avenue NE, and Main Street. BAT lanes are exclusively for buses, but drivers in other types of vehicles can use them to turn right into driveways.

Current state law prohibits any private vehicles, including employer shuttles operated on behalf of companies like Amazon and Microsoft, from using those same lanes as a public transit vehicle would.

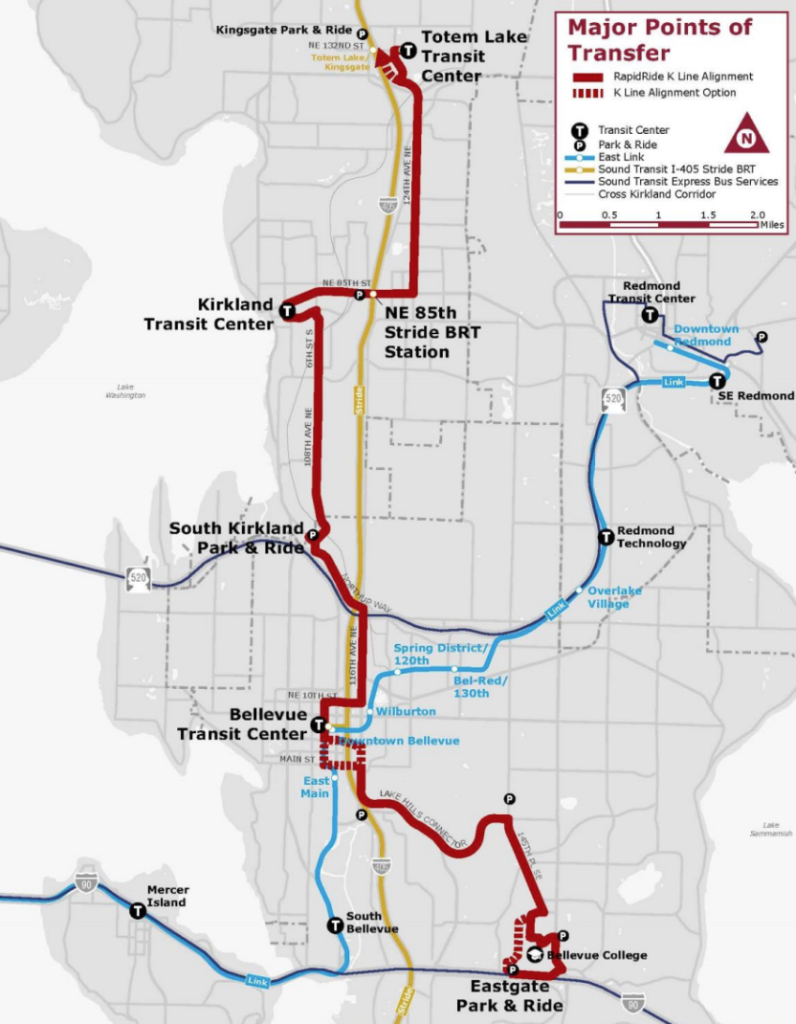

The bus lanes would save seven minutes of expected travel time through the entire downtown corridor compared to doing nothing, according to a presentation by Ryan Whitney, Metro’s K Line lead. For the entire corridor between Totem Lake and Eastgate, Metro expects to decrease travel times by 23% to 27%, depending on the direction of travel, which translates to a staggering 20.5 minutes and 26.5 minutes of saved time for riders.

But last fall, numerous members of the Bellevue City Council expressed interest in allowing employer shuttles to use these potential bus lanes, at the behest of Amazon. The move was clearly intended to blunt bus lane pushback in Bellevue and appease major employers. With approximately 14,000 employees currently working in Bellevue, Amazon operates a dedicated shuttle during commute times, and also contributes funding to operate the Bellhop, the public, on-demand five-seat shuttle that operates throughout downtown.

“We appreciate the city’s efforts so far to champion allowing employer shuttles to utilize BAT lanes on the K Line,” Pearl Leung, Amazon’s senior manager of public policy, told the Bellevue Council in November. “Helping mitigate traffic congestion as we grow in Bellevue is a top priority for us. Our shuttle program has been one of the most effective ways to help take cars off [the] road. Being able to use BAT lanes would make this process even more efficient and an even better alternative to driving alone.”

Empowered by the appointment of Bellevue Councilmember Janice Zahn to the Washington House of Representatives in January, the idea of changing state law to remove the existing language standing in the way of making this change has become a focus of Bellevue’s city administration.

“I know the timeline is quick, but we have a hot line to Representative Zahn now,” Bellevue Mayor Lynn Robinson said last week at a council discussion on the K Line. At that meeting, Zahn announced she would be stepping down from the council at the end of March.

Metro’s initial response to the idea of allowing private shuttles to use BAT lanes has been cautious. Last week’s meeting brought Chris O’Claire, the director of Metro’s mobility division, to Bellevue to provide the agency’s current thinking on the issue.

“King County Metro recognizes that there is an opportunity for us to look at maximizing the use of our right-of-way,” O’Claire told the council. “In this, we really want to make sure that we look at the safety and the operations of the roadway. […] Some bus lanes make sense, and some — I’m just going to use Third Avenue downtown [Seattle], don’t make as much sense, based on the density, the usage, etc. So we’re really looking at somewhat of a tiered system, is where Metro is very interested.”

O’Claire brought up the existing Employer Shuttles Program in Seattle, where an agreement between the City and Metro allows major employers to pay to utilize public bus stops for shuttle pick up and drop off. Adopted as a permanent program in 2023, Seattle charges a $600 annual fee per vehicle, along with a $5,000 charge per bus stop. That fee can be reduced for institutions like universities and hospitals that utilize the shared stop program to achieve their commute trip reduction goals. She shared stop program has largely been a success since it started as a pilot in 2017, but allowing private shuttles to utilize dedicated transit lanes would take things even further.

“Right now, King County Metro would like to understand the impacts, to operations, to safety, and to investment in public transit, and really a path forward on how we can work with the jurisdiction, in case something changes — whatever it might be: mode splits, how people are moving, what it might look like,” O’Claire said.

Unless state law is significantly overhauled, cities still wouldn’t be allowed to let private vehicles that carry fewer than eight passengers access BAT lanes, so the flood gates wouldn’t be opening to anti-transit jurisdictions seeking to render transit lanes completely useless. With strong opposition to BAT lanes sprouting up in some corners of the region, most recently along the proposed Stride bus rapid transit corridor in Lake Forest Park, this concern isn’t merely theoretical.

Ultimately, there’s another guardrail included in state law, providing that private vehicles can use dedicated facilities so long as “such use does not interfere with the efficiency, reliability, and safety of public transportation operations.” But that doesn’t mean that cities are always going to be on the same page with agencies about their efficiency and reliability goals.

With only a week left to introduce new bills at the state legislature and get them approved by a policy committee, the idea is unlikely to move forward this year. Still, discussions are poised to continue behind the scenes. The K Line is not set to open until 2030 — or potentially later, if federal funding for transit projects becomes scarce over the next four years.

“I have been working on something to drop this legislative session, if we can actually come to some agreement with Metro that this is something that makes sense for them as well,” Zahn said. “We’re not talking about something where Metro would absolutely be in the driver’s seat, but really, removing the state prohibitions so that the collaboration and discussion can actually happen.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.