Growth at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport (SEA) continues at a fast clip with new service, expanded and improved facilities, and booming passenger volumes. The airport has fully emerged from the pandemic period with a new record of 52.6 million passengers in 2024, besting 2019’s record of 51.8 million. Passenger volumes were up about 3.5% from 2023 despite the grounding of Boeing 737 MAX 9’s early in the year, due a midair door plug blowout.

The Port of Seattle projects another year of increased passenger volumes, rising another 1.7% to 53.5 million in 2025.

Domestic passenger volumes were slightly above 2019 levels with about 46 million, a 0.1% increase. But the bulk of increased passenger volumes has come from international travel, rising 15% from 2019 levels to around 6.6 million passengers.

2024 saw the addition of eight new international connections with service to Taipei–Taoyuan (STARLUX Airlines, China Airlines, and Delta Airlines), Munich (Lufthansa), Chongqing (Hainan Airlines), Toronto–Pearson (Alaska Airlines), Manila (Philippine Airlines), and Liberia, Costa Rica (Alaska Airlines). More international connections have already been announced for 2025 with Kelowna (WestJet), Zurich (Edelweiss Air), Copenhagen (Scandinavian Airlines), Seoul (Hawaiian Airlines), and Tokyo–Narita (Hawaiian Airlines).

Buttressing this growth, the Port of Seattle is marching toward a substantial expansion of the airport. Last fall, the agency released its draft Sustainable Airport Master Plan (SAMP) Near-Term Projects Environmental Assessment. It’s an important milestone as the agency tries to obtain authorization from federal and state partners to approve a lengthy project list, complete design and engineering, and advance toward construction.

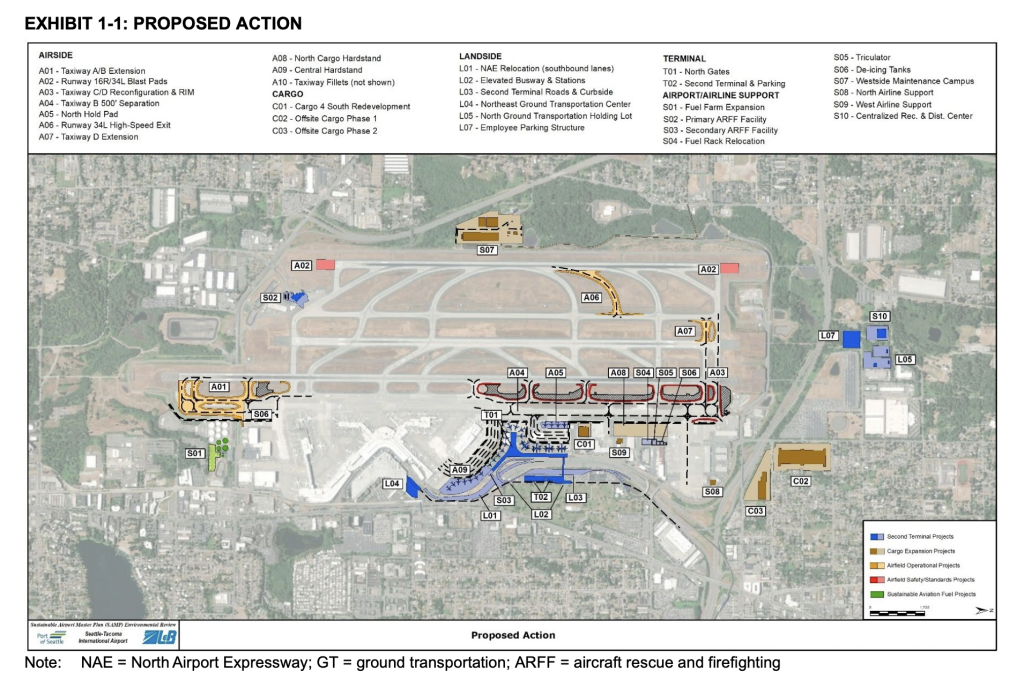

All told, the near-term projects list includes over 30 different project items. Individual project scopes differ wildly, but include airfield improvements, relocating existing facilities through new construction, building new roadways and infrastructure, and creating a brand new terminal.

The near-term projects list was developed with the intent of increasing airport capacity for passengers and cargo while reducing aircraft delays and congestion within a reasonable timeframe, which the SAMP is targeting for 2032. The SAMP suggests that those projects would be able to better accommodate 56 million passengers per year and ensure that the airport operates at a much higher level of service.

Proposed projects would help the airport reach a Level of Service of B. That’s a considerable improvement over the Level of Service D that the airport has been operating under with existing facilities and demand. However, the trajectory of passenger growth could easily exceed 56 million passengers by the time the project list is completed, eventually leading to lower levels of service than the SAMP suggests. In fact, within five years of completing the near-term list, the Port of Seattle expects to see over 64 million passengers pass through airport facilities.

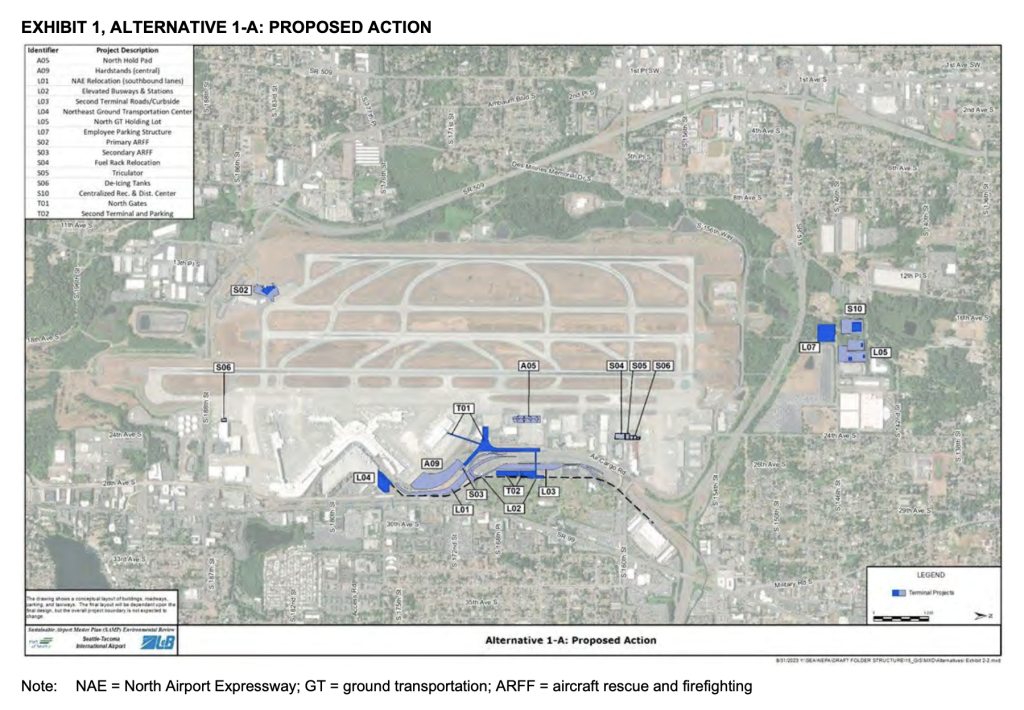

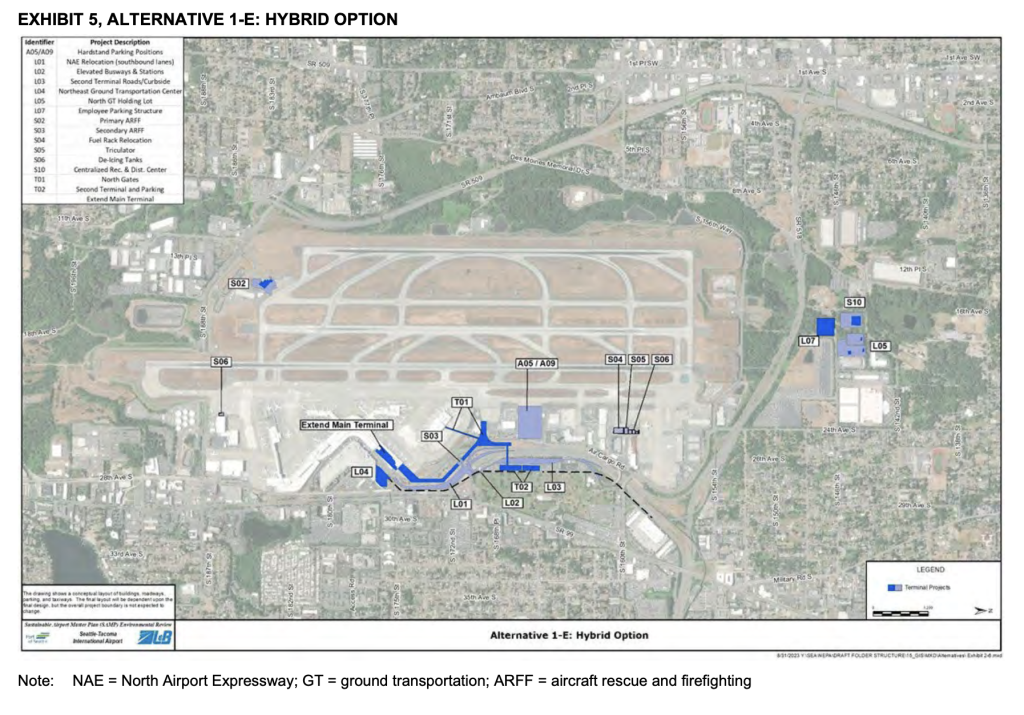

The new terminal will be north of the existing terminal, situated just to the north of the D and N Concourses. The question, however, is in what form as the Port of Seattle is considering two competing options. One option, which is the preferred alternative, would make the new terminal a standalone terminal. The other option, which is considered the hybrid alternative, would directly connect to the existing terminal but still be a terminal in its own right.

The preferred alternative would require relocation of a portion of the North Airport Expressway, fire department, and other support facilities to construct the airside terminal. The expressway itself would be pushed, more or less, to the east to make space for new hardstands and terminal concourses and expanded with two more lanes on some portions. The new structure would be Y-shaped, stretching as far north as the control tower, and contain three stories of space — across 609,000 square feet — to house passenger holdrooms, retailers and restaurants, and other amenities.

A skybridge from the terminal would provide a direct connection to the N Concourse, post-security. In addition, the new terminal’s check-in, baggage claim, security screening, and 1,350-stall parking garage would be located on the current grounds of the Doug Fox surface parking lot (1,620 stalls) with a skybridge over the expressway to connect to the airside terminal area.

The hybrid alternative requires most of the same relocations as the preferred alternative, but jettisons a few. The airside terminal would be directly connected to the existing terminal, snaking along the realigned expressway to the existing D Concourse. This would require closure of the D Concourse Annex, which currently provides shuttle bus connections to and from planes that serve passengers from remote hardstands.

As with the preferred alternative, the hybrid alternative would provide a skybridge connection to the N Concourse as well as to the new terminal check-in, baggage claim, security screening, parking garage facility east of the expressway, and 19 gates. It also has the potential for the inclusion of moving walkways within the airside terminal.

Along with both new north terminal alternatives, the Port of Seattle would construct a new passenger ground transportation facility and elevated busway.

The transportation facility would be situated in an area immediately next to the central parking garage and sandwiched between the airport expressway and Link light rail station. The area is currently a paved surface area and was previously conceived as space for a hotel. For passengers, the transportation facility would offer an indoor space with amenities, such as shops and seating, as well as a meeting place to catch shuttles, taxis, ridehails, and chartered services. Passengers would also be able to take shuttle buses from the main terminal to the new terminal and the rental car facility.

Another benefit is that the Port of Seattle is planning to construct a moving walkway system, which would speed up the walk between the light rail station and main terminal (about a 1,000-foot walking distance). That space would be fully protected from the elements, increasing comfort and decreasing pollution from the neighboring 13,000-stall garage and roadway.

In terms of the busway, it would offer a relatively quick connection between key airport facilities. The proposed facility would be exclusively for buses end-to-end from the new transportation facility and car rental facility, though it could potentially be used for some private shuttles. That has yet to be formally decided. For passengers, frequent shuttle buses would serve three stops along the busway. The Port of Seattle expects that those shuttle buses would operate at least every five minutes but frequency could be even better.

Though moving walkways have been a consistent request from passengers that use light rail, some demand exists for others throughout the airport. Agency spokesperson Perry Cooper said that none are planned for installation within existing concourses or the main terminal itself, as part of the SAMP. That’s because existing concourses within the main terminal are relatively narrow, making it challenging to fit moving walkways without affecting other passenger flows and circulation within those spaces or necessitating widening of concourses, which have their own knock-on impacts and challenges to gate ramps.

Consequently, passengers needing to go from the new north terminal to the S Concourse may find themselves having to make a long and varied journey: a walk across the skybridge from the north terminal to N Concourse and a three-seat ride on the SEA Underground, the automated airport subway, from N Concourse to the northern portion of main terminal (Green Line), then from there to southern portion of the main terminal (Yellow Line), and finally from there to the S Concourse (Blue Line).

Shuttle buses weren’t being considered at this time between gates and terminals, but there have been agency discussions about future modifications or additions to the SEA Underground, whether below or above ground, Cooper said.

A north terminal to S Concourse connection may not necessarily be the norm for most passengers, but it does demonstrate the challenges of a sprawling airport facility and a real headache for connecting international travelers that may need to budget extra time for a connection. That said, the new terminal is likely to trigger a significant realignment of airlines and gate locations, so certain airline tenets could be strategically placed at the new terminal to reduce the likelihood of difficult connections between terminals to make connecting flights.

In addition to the SAMP, the Port of Seattle is still making significant interim improvements to the airport. Examples include expansion of the C Concourse for public and dining, relocation and expansion of security screening areas, enhanced check-in facilities in the Alaska Airlines zone, and a complete modernization of the S Concourse.

Formal design and engineering of the proposed near-term projects could begin as soon as this year, but the earliest date for construction would be sometime in 2026. Construction of new and expanded buildings is normally a multi-year process and there is a high likelihood that the new terminal would open among the last of projects given the phasing and relocation of other facilities to accommodate it. As for the environmental process, the Port of Seattle expects to conclude that this year in phases.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.