A recent study of identical twins illustrated the value of living in a walkable neighborhood, showing a strong correlation between walkable neighborhoods, time spent walking, and positive health outcomes. Simply put, it appears that people tend to lead healthier lives in walkable neighborhoods. Published in the American Journal of Epidemiology in December, the study used an index to rate the walkability of a neighborhood and measured health outcomes by using self-reported weekly minutes of walking and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, as well as days per week that study respondents used transit services.

Although the twin study incorporated nationwide data, its results can be used to inform improvements to infrastructure in Seattle. While some neighborhoods in Seattle are very walkable, others need significant changes to increase access to amenities on foot. By increasing walkability across the entire city, Seattle can encourage healthier lifestyles and outcomes for all its residents, instead of just a few.

Twins are used for studies like this because it can reduce or eliminate potential differences between “participants” in the study. “We can’t randomize people to live in different neighborhoods,” said Professor Glen Duncan, lead author of the paper and chair of the Department of Nutrition and Exercise Physiology at Washington State University. “People live in the neighborhoods they live in for a variety of reasons, including social stratification, driven by economic issues, or locations, jobs and even genetics.”

A twin study helps to reduce these other possible explanations, called confounding factors, by comparing people who come from the same backgrounds, with the same genetics, and often the same social and economic standing.

The study’s walkability ratings weighed factors such as population density, the density of intersections, sidewalk completeness, and the density of services in that area. These types of measures give an indicator of how walkable a neighborhood or area is, so that cities can easily be compared on common footing. One scoring system widely used in real estate is WalkScore, which also attempts to standardize measures of walkability. Seattle currently has a citywide WalkScore of 74, although neighborhoods vary considerably. Similar to the study’s rating, WalkScores are calculated based on distance to amenities, population density, block length, and intersection density.

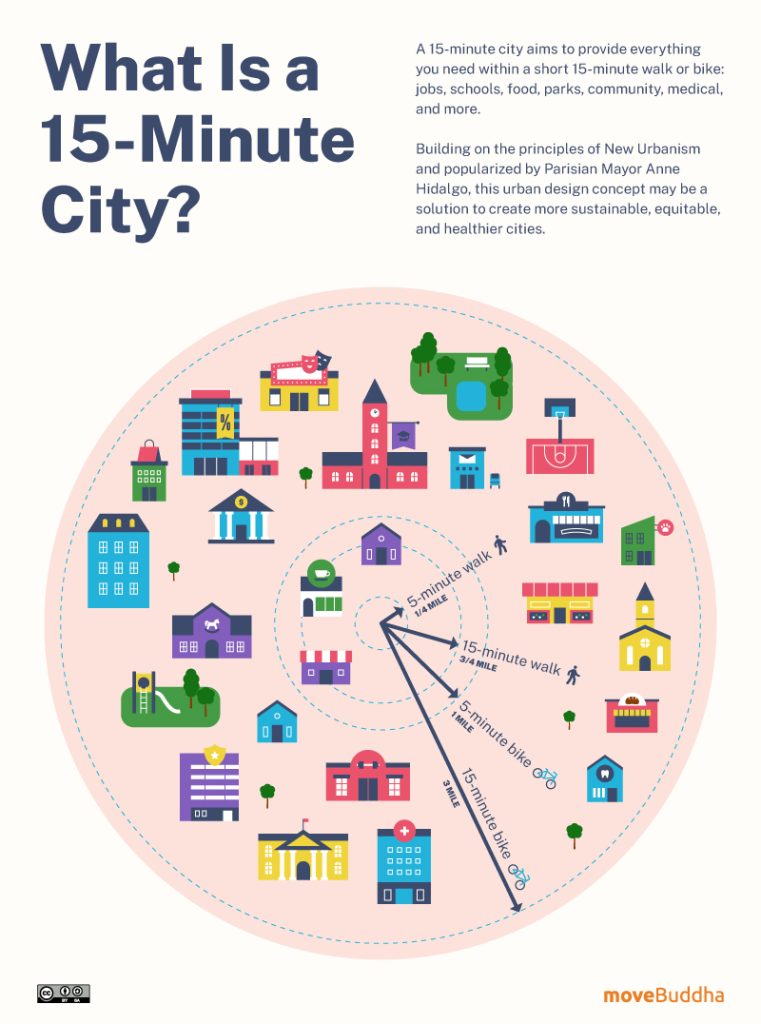

Despite Seattle’s high WalkScore, walkability benefits are not distributed equally. Some of the highest WalkScores belong to International District, Belltown, and First Hill, all with a WalkScore of 98. Others, like Rainier View, Matthews Beach, and Arbor Heights received WalkScores of only 22, 33, and 38 respectively. Nat Henry, a professional geographer based in Seattle, carried out detailed research on Seattle’s walkability and found that “only 44% of Seattleites can walk to basic city amenities.” Some neighborhoods, including large parts of West Seattle, Delridge, and Northeast Seattle do not have access to basic amenities within a 15-minute walk.

Part of increasing walkability includes increasing the density of homes and amenities and making sure roads have footpaths, crosswalks, and slow speed limits.

“Fundamentally, walking is a short-distance mode of transportation,” said Gordon Padelford, Executive Director at Seattle Neighborhood Greenways. “So if you want to encourage walking you need stuff to be close. It sounds super basic, but I think sometimes it’s worth starting there. If you don’t have things that people need to walk to within half a mile, people just won’t walk to them.”

Improving walkability in Seattle’s neighborhoods could greatly impact public health. Research has shown that regular physical activity reduces the likelihood of developing heart disease, diabetes, cancers, and osteoporosis, as well as other illnesses and conditions, and can also generally improve mental health and quality of life. Studies like Duncan’s twin study can support arguments for policy and infrastructure changes that increase walkability.

“We don’t want it to just sit in a journal and be read by a bunch of other scientists,” said Duncan. “We want that information to get in the hands of policymakers and decision-makers. […] If infrastructure changes and neighborhood changes can elicit activity in such large samples, that’s a real big win for public health.”

Walking is the most frequently reported physical activity for US adults and is one of the most accessible, as it doesn’t require special equipment or skills. “If walking is the most common [physical activity] and physical activity is good for you, anything that increases access to walking can be said to be promoting public health,” said Andrew Dannenberg, author of Making Healthy Places, and affiliate professor in the Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences and the Department of Urban Design and Planning at the University of Washington. “It’s that simple.”

In addition, the twin study found higher walkability in cities potentially caused the increases in walking and physical activity. While causality is difficult to pin down and further research needs to be done, the study and others like it hope to find evidence for measures (like increasing walkability) that could improve health outcomes.

“Give people places to walk, and they will walk,” Dannenberg said. “Public health does not build sidewalks. Sidewalks and places to walk are built by the planners and developers, architects and landscape architects and so on. … It’s important for public health to work with those fields to get the places created, because we know that if you create the places, people will use them.”

When creating these walkable areas, it’s also important to make them high-quality. Criticisms of WalkScore and other metrics like it often touch on the fact that they overlook important factors like road width, lighting, street safety, curb extensions, tree canopy, or local crime rates. Such factors can weigh heavily on the perceived comfort of walking in a particular place. Cities need to ensure that they don’t just make homes, jobs, and amenities close together, but that the routes between them are high quality and accessible to all.

“The quality of the infrastructure makes a big difference,” said Danneberg. “You can have a sidewalk full of bumps and potholes and missing pieces and no curb ramps, that’s utterly useless to somebody in a wheelchair. So it’s not just having it, but having the quality.”

Some important interventions include reducing speed limits, increasing the number of street trees and street lights, installing benches and public toilets, extending transit options, and ensuring that buildings include points of interest, such as storefronts, windows, or art, and are well-maintained.

“If we’re really going to create walkability, it’s not enough to have sidewalks, it’s not enough to have crosswalks, it’s not enough to have destinations to go to,” said Padelford. “You also have to make the walking experience safe and comfortable.”

To capitalize on pedestrian upgrades and urban design improvements, cities should actively encourage people to walk and opt for active mobility over car use.

“Just building it alone may not be sufficient,” said Danneberg. “But building it plus doing some promotion of using it, having some programming, having some public awareness and community engagement, then building it and getting people to use it does increase physical activity.”

Importantly, Duncan said that policymakers cannot simply rely on approaches that push individual behavior change: “We tell people to get their 150 minutes per week of moderate to vigorous physical activity. We tell people to eat their fruits and vegetables. It’s not easy in the real world to do that. We need to give people the infrastructure to actually pull that off.”

This approach is also supported by The Guide to Community Preventive Services, a set of evidence-based recommendations from public health experts funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and selected by the CDC. One of their clear findings is that more park, trail, and greenway infrastructure (which includes urban routes for walking, hiking, or cycling) “increase the number of people who engage in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in the park, trail, or greenway.” In support of these interventions, the guide recommends community engagement and public awareness raising, as well as programs for physical activity and social interaction. In addition, increased transportation connections, street crossings, and expanded hours of operation (for public transit) can help.

For changes to be made to Seattle’s streets, several factors need to fall into place, many of which groups like Seattle Neighborhood Greenways are advocating.

“You need the plan, you need the policies that come with that, you need the funding and you need the public support,” Padelford said. Last year, Seattle adopted a new transportation plan to cover the next 20 years, which Padelford views as a positive step. “We have the plans now, and Seattle’s policies are quite good. If you go and you read what Seattle intends to do, [the policies are] all very thoughtful.”

Two of the major constraints that lie in the way of improving walkability are NIMBYism (not-in-my-backyard activism), and getting the appropriate budgets for the required infrastructure changes.

“We don’t have nearly enough funding for all the sidewalks in Seattle,” Padelford said. “That’s one big challenge: there’s a multi-billion dollar backlog of needed sidewalk infrastructure. … it’s a daunting dollar figure.”

While Seattle residents tend to be quite positive towards walkability, there are still barriers.

“Occasionally, you get pushback, if someone has to lose some parking to build a sidewalk,” said Padelford. “Any time where there is a perceived loss of vehicle throughput or storage, that’s where controversy tends to erupt, and which is too bad.”

Improving public buy-in for changes that reduce space allocated to cars could allow changes to be made more quickly and without so much resistance, contributing to faster public health benefits for Seattle residents. Duncan believes there is a false choice between cars and walkability that may be part of the problem.

“All too often there’s this unnecessary dichotomy,” Duncan said. “We hear it called the war on cars, or the war on the automobile. It just doesn’t have to be that way. It’s not either or.”

Duncan’s team also carried out a longitudinal study that is currently in peer review. This new study hopes to find more evidence of a causal connection between walkability and walking. The study looks at whether changes in the “exposure”, i.e. changes in neighborhood walkability, are associated with changes in physical activity. This change in walkability could occur, for example, when a person moves to a different neighborhood, or the neighborhood infrastructure itself is changed. This study, while not yet published, has found evidence that further indicates walkable neighborhoods may encourage people to walk more.

Planners, environmental advocates, public health experts, cyclists, and other residents who want to see more walkability and healthier urban planning all have a role to play in ensuring outcomes from such research.

“I would encourage folks to get involved at the local level and help transform their streets,” said Padelford, emphasizing the capability of Seattle residents to make urban change. “I always tell our volunteers that our streets were built to reflect the values and priorities of people who came before us, and we can rebuild them to reflect the values and priorities of the communities that are here now. We do not need to hold to our grandparents’ vision for our streets.”

When there are so many benefits from walkable neighborhoods, including potentially major public health gains, the decision to transform Seattle into a more walkable city seems like a no-brainer.

Leah Hudson is an editor and writer published by Insider, Atlas Obscura, and Penguin Random House New Zealand. Leah loves to write about sustainable urban development, mental health, and matters of the heart. She spends her time reading, walking her dog, and eating unreasonable amounts of chocolate. You can find her at https://leahhudsonleva.com/.