At least three groups have filed an appeal contesting the environmental review of Mayor Bruce Harrell’s One Seattle Comprehensive Plan, which adds housing options across the city, ahead of a Thursday deadline. Residents in Madison Park, Hawthorne Hills, and Mount Baker backed the appeals, which seek to require additional environmental review beyond the lengthy 1,300-page analysis that the city has already completed, delaying zoning changes. Taken as a whole, the appeals amount to a last-ditch attempt to maintain the status quo from residents in some of the city’s wealthiest and most amenity-rich neighborhoods.

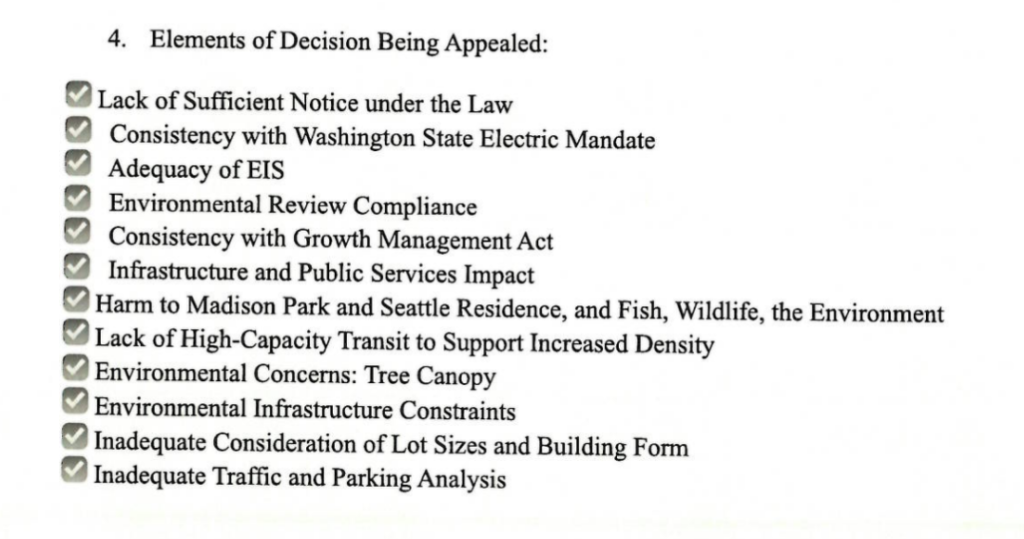

As is custom in predatory delay, the appeals use an everything-but-the-kitchen-sink strategy, citing a variety of potential impacts covered under the State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA) that they allege the City didn’t consider deeply enough. Those include a purported lack of stormwater infrastructure, lackluster transit service, tree canopy loss, on-street parking impacts, and an alleged harm to historic resources. Seattle’s Hearing Examiner will likely dismiss many of these issues, but the goal is getting one of them to stick, at least long enough to delay the plan’s implementation.

“The One Seattle Plan will cause significant impact to our specific community yet at no point in the 1300 pages of the FEIS [Final Environmental Impact Statement] is Madison Park and its unique location addressed,” states the appeal filed by Friends of Madison Park, a neighborhood group formed in 2023. “The One Seattle Plan will cause significant impact to the historic nature of our neighborhood and yet FEIS does not adequately consider the aesthetic impacts (height/bulk/scale/view) of the One Seattle Plan in a historic business district such as Madison Park. Madison Park is not even mentioned in the historic summary provided, although its history as an indigenous hunting area and early development is significant.”

The Madison Park group alleges stormwater upgrades are necessary before the neighborhood could countenance housing growth.

“Madison Park filed an Appeal to have a supplemental EIS conducted because our neighborhood is lake bottom and already has significant drainage issues and no stormwater system to manage them,” Friends of Madison Park President Octavia Chambliss told The Urbanist via email after the appeal was filed. “We have walked our neighborhood with [Councilmember] Joy Hollingsworth, and neighbors have submitted comments to the Council members- pro, con and in-between regarding the One Seattle Plan. Madison Park is not opposed to urban growth and the need for up zoning, and we want to work in partnership with the City to implement this growth.”

A separate appeal by two Madison Park residents, Trevor Cox and Jake Weyerhauser, included identical language to the Friends of Madison Park appeal, including an allegation that the city “failed to provide sufficient notice to involve the public in the SEPA process.”

While many opponents of the One Seattle Plan have been pushing for the city to send a mailer to every single resident in the city, there is no such requirement under state law, and the city’s Office of Planning and Community Development held public hearings on the draft EIS last year, on top of numerous other community meetings and open houses.

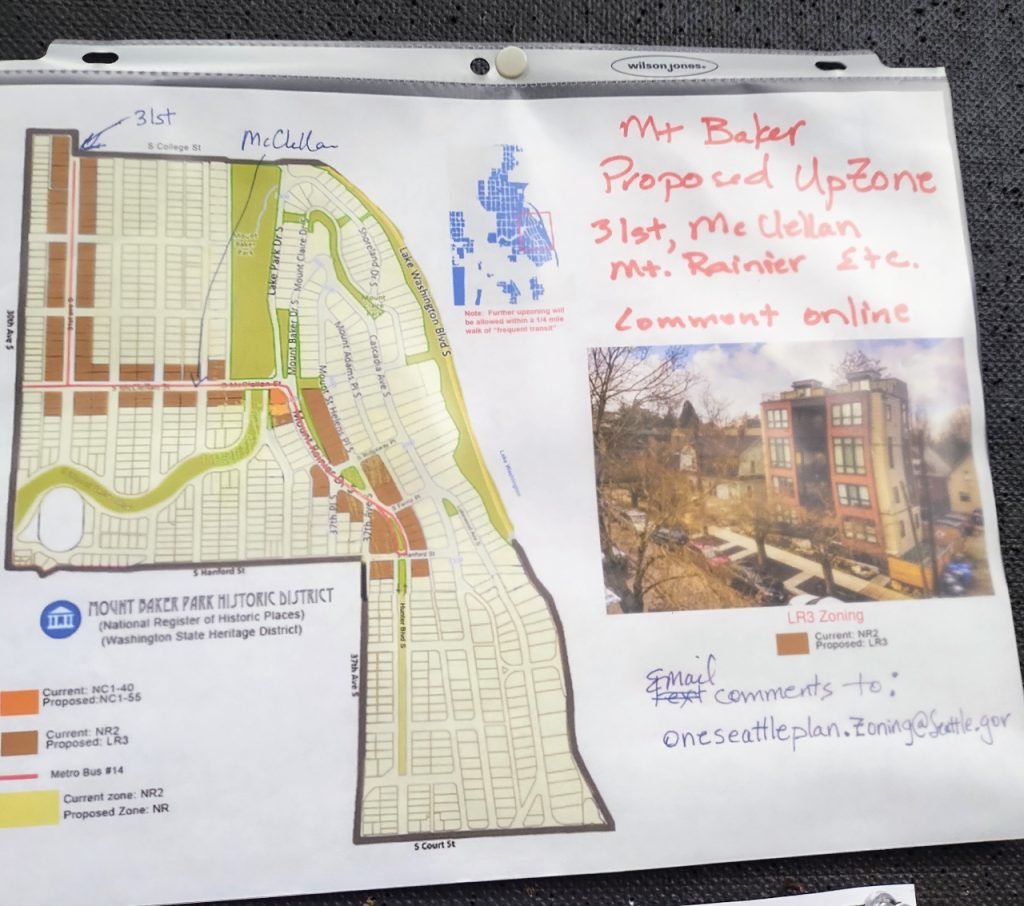

Two appeals by residents in Mount Baker, led by attorneys Chris Youtz and John M. Cary, bring up similar issues, and also argue that the city didn’t do enough analysis on the unique character and historic nature of the initially redlined Mount Baker neighborhood. Those two appeals allege that the city’s lack of analysis around any deed covenants that still may be in place is a basis to re-do the environmental analysis.

“[The] City’s disregard of deed covenants that limit construction to one single family home per lot and are intended to preserve the character of the neighborhood,” reads one listed complaint in Cary’s appeal, joined by six other residents of Mount Baker’s most plush streets. “This amounts to interference with contractual rights, a taking of property without compensation and an inducement to developers to violate such covenants resulting in unnecessary legal expenses for developers and property owners.”

In practice, the city has no role in enforcing restrictive covenants but they could ultimately impact what is able to be developed in neighborhoods like Mount Baker, regardless of changes in zoning.

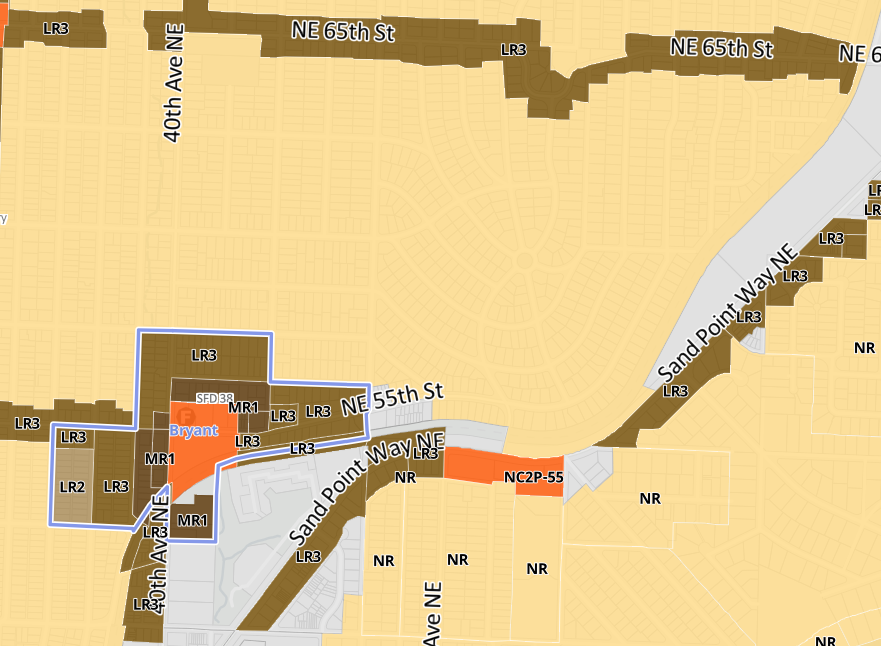

The appeal filed by the Hawthorne Hills Community Council, a group that has been pushing to remove the proposed Bryant neighborhood center focused around the NE 55th Street Metropolitan Market, stresses the impact of reduced minimum parking requirements. But the state legislature exempted lowering or removing those requirements from SEPA analysis in 2023.

“We believe that approval of these zoning changes would be tantamount to sanctioning a transportation crisis that would ripple through our entire neighborhood,” that appeal states. “The lack of analysis of parking and street use impacts due to zoning changes results in an EIS that does not meet adequacy.”

Appeals like these have delayed some of Seattle’s biggest housing moves over the past decade, including 2017 urban village upzones passed as part of the Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda (HALA) and accessory dwelling unit (ADU) reform. The ADU appeal delayed legislation by two years, but the City’s ultimately passed an even stronger reform than initially proposed.

Since then, the Washington State Legislature has approved a number of bills limiting the ability of local residents to file SEPA appeals and reducing opportunity for lengthy delays.

Senate Bill 5818, approved in 2022, exempts “[t]he adoption of ordinances, development regulations and amendments to such regulations, and other nonproject actions taken by a city […] that increase housing capacity, increase housing affordability, and mitigate displacement” from legal challenge under SEPA, with a narrow exception for actions that may have an impact on fish habitat.

While any appeal is active, the Seattle City Council won’t be able to advance any aspect of the plan, which includes any potential votes on amendments. But the council’s Select Committee on the Comprehensive Plan can continue to meet and discuss the plan, though its chair, District 3 Councilmember Joy Hollingsworth, could decide to cancel those meetings and wait out the appeal.

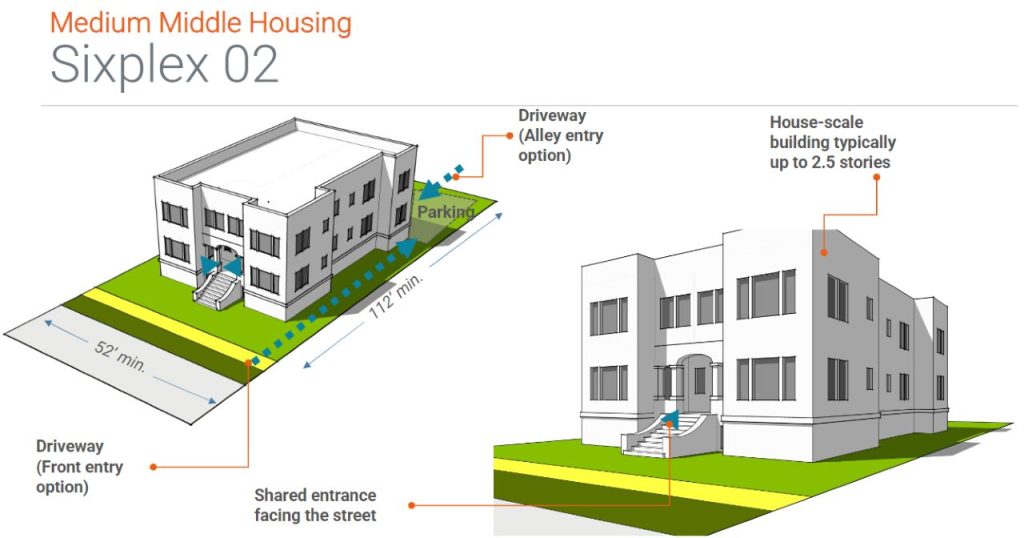

The City faces a time crunch, with a need to adopt zoning changes allowing new statewide minimum residential density standards across the city by July 1, in compliance with 2023’s HB 1110. If the city does nothing, then a model code created by the state’s Department of Commerce takes effect, a code that is generally more permissive than the one Seattle is set to adopt. One way or the other, fourplexes will be legal citywide by July 1, with the minimum standard raising to sixplexes within a quarter-mile of frequent transit or if two of the units are set aside as affordable.

At a minimum, these appeals, which are likely to be consolidated into a single case and considered as a whole, could push the Comprehensive Plan process, already months behind schedule, back an additional two to three months.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.