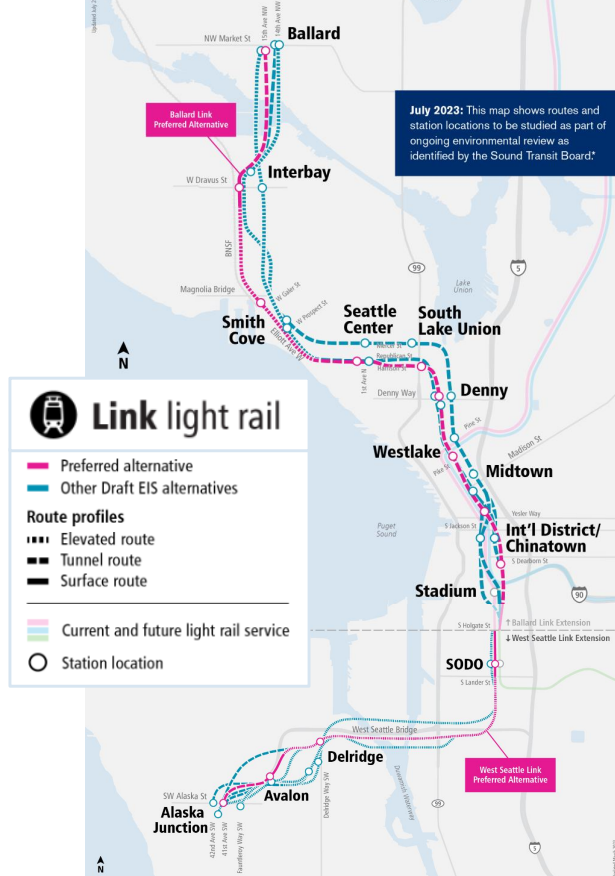

With Sound Transit continuing to advance planning and design work on Seattle’s West Seattle and Ballard light rail extensions, the City of Seattle has unveiled a suite of code amendments that are aimed at streamlining permitting for these two transformative megaprojects. In the works for nearly half a decade, these updates overhaul a land use code that isn’t really built to accommodate light rail stations, much less the 13 stations planned as part of these two lines.

Permitting these two projects, which were approved as part of the Sound Transit 3 (ST3) funding package in 2016, is set to be a titanic task for the city, with a broad array of new city employees planned to be brought on over the next two years to help get it done. West Seattle Link alone, which only includes four stations between SoDo and Alaska Junction, is set to require 89 individual Master Use Permits dealing with different elements of the line — an illustration of how complicated the permitting regulations in place around new transit facilities are.

Seattle has permitted light rail stations before, of course, but the size and scale of the planned ST3 projects is prompting the City of Seattle to look at ways it can systematically lower barriers to getting elements of the project permitted, as part of a partnership agreement with Sound Transit that goes back to 2017. Last week, the city’s dedicated ST3 team briefed the Seattle Design Commission on these updates. That commission has already started reviewing early designs for stations and key guideway segments, but as part of this update, it will become the official advisory body for light rail facility design in the city.

“In totality, both of those projects are the largest infrastructure project that the city has ever seen,” Lindsay King, an ST3 project manager with the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections (SDCI) told the commission last week at a briefing. “It’s going to be hard to deliver this project, and it’s going to be even harder to do it on time, given that permitting is hugely complicated in the city. So we have a shared goal to try to streamline the permit process and to remove obstacles where possible, while still fulfilling our regulatory role and delivering in the public’s best interest as well as mitigating impacts of the project.”

One of the biggest changes proposed here is a unique set of development standards that only apply to light rail facilities. Without this update, stations would have to adhere to each neighborhood’s unique development standards — which weren’t designed with a light rail line in mind.

“Light rail, from north to south, will cross 19 different zones in the city, with 19 different sets of standards that would be applied to light rail transit facilities,” King said. “That is problematic from a number of fronts, mostly [the fact that] those standards were designed for residential, commercial, industrial buildings. They were not designed for a linear transportation facility, and would create different outcomes north to south across the city.”

The development standards are complimentary to new light rail station design guidelines approved by the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections (SDCI) and the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) in 2024. They essentially act as baseline requirements, and address many of the same issues that are the subject of Seattle’s much-maligned design review process, including required modulation on the exteriors of station buildings, the maximum amount of blank facade allowed, and requirements around overhead weather protection.

Ultimately, it would be up to either the SDCI or SDOT Director to decide whether to grant an exception from any of these rules, with the Seattle Design Commission providing recommendations on how to implement them. To the extent that creating bespoke station designs that reflect the character of the immediate neighborhood adds costs, those costs will still be imposed, but with a little less bureaucracy and red tape.

Another major element here would limit the ability for decisions around ST3 stations to be appealed. In the context of projects of the scale of these two light rail lines, a few months delay can add hundreds of millions of dollars in extra costs and would likely push opening dates, already set to be several years later than what was promised to voters, back even more. Decisions around light rail permitting would not be able to be appealed to Seattle’s Hearing Examiner, a process with a relatively low barrier to entry, and instead have to be appealed directly to King County Superior Court. As for a variance from the city’s requirements on noise during the construction period, that could be appealed — but only once.

“If not addressed, allowing appeals for dozens of construction-related permits would substantially increase the risks of unpredictable time delays and significant cost increases for the completion of this essential public facility,” SDCI’s analysis of the proposed code change noted.

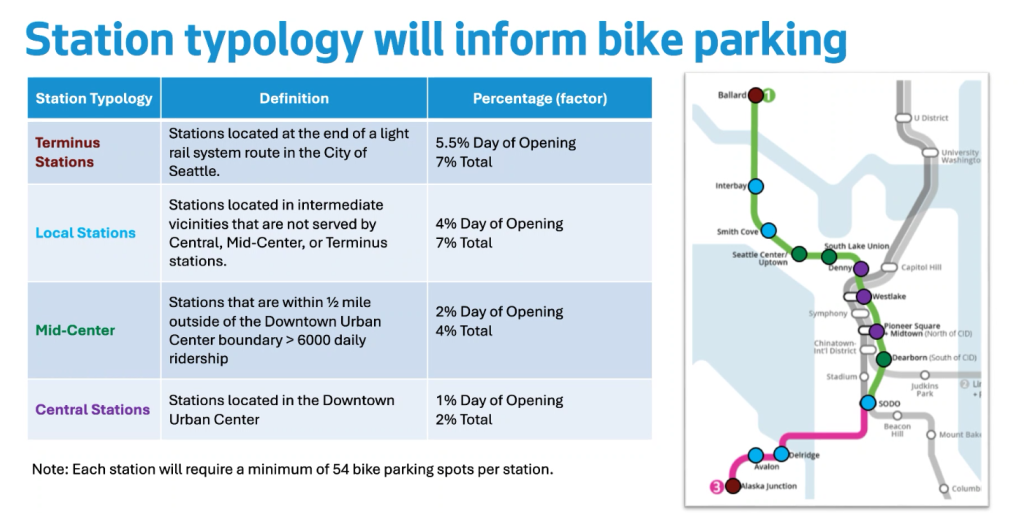

New bicycle parking standards for light rail stations

The ST3 code updates also create a brand new framework for bicycle parking at Seattle’s future light rail stations. Since Sound Transit finalized the design of the Sound Transit 2 light rail stations — ones like University of Washington and Northgate — Seattle has significantly overhauled its bicycle parking requirements, beefing up standards for providing spaces for Seattleites to stash a bike at home or the office. But those standards aren’t designed for light rail stations either, and would be one-size-fits-all for every ST3 station.

Instead, the city’s ST3 team is proposing a four-tiered system with varied parking requirements depending on a station’s characteristics. The framework assumes that 50% of riders bringing a bike will take their bike on a train, and also assume stations at the end of a line — at places like Ballard and Alaska Junction — will see the highest amount of people arriving at the station by bike. The closer a station is to downtown, the least amount of bike parking it’s assumed that a station will need, but the code will require a bare minimum of 54 bike parking spots everywhere.

“The current requirements need to be revised because they lack sufficient detail to define a reasonable minimum requirement,” SDCI’s analysis states. “For example, if no changes to this code are made, Downtown stations could be required to provide several hundred bicycle parking spaces which would be unnecessary based on anticipated demand, as well as physically challenging and prohibitively expensive to incorporate into the planned light rail station footprints.”

And then there’s the issue of trees. Tree removal and potential compliance with the city’s policy of adding three new trees for every one replaced is a big focus of existing permit requirements, but are another thing that doesn’t make sense in the context of a project of this scale.

“Let’s say there’s 300 permits total [for West Seattle Link] — grading, demo, building, master-use permits,” King said. “Right now, in a do-nothing scenario, we are assessing tree impacts and mitigation 300 times on 300 different permits. What we intend to do is something better than that, and we intend to create a tree and vegetation management plan consistent with what we’ve done with other major projects like the SR 520, the UW Master Plan and Seattle Parks Department, where you have one stop shop that assesses impacts mitigation for trees each project.”

These code updates are expected to head to the Seattle City Council within the next few weeks, with final approval expected by early spring. The package is a clear sign that permitting work is expected to ramp up soon on West Seattle Link, with construction expected to start in 2027 for a 2032 start of service. After a series of planning delays, Sound Transit is hoping to launch Ballard Link in 2039 following nearly a decade of construction.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.