The land use advocacy nonprofit Futurewise is taking the City of Mercer Island to a state appeals board over serious concerns that the city’s Comprehensive Plan doesn’t go far enough to promote housing affordability in compliance with state law. The appeal, filed last week at Washington’s Growth Management Hearings Board, alleges that Mercer Island’s 20-year growth plan doesn’t allow enough types of housing, including emergency shelter and affordable housing, nor does it plan for enough housing in the area around its forthcoming Sound Transit light rail station in alignment with the region’s transit-focused growth strategy.

The appeal alleges a “failure to identify sufficient land for STEP housing, the failure to document programs and actions needed to achieve housing availability including funding gaps, the failure to adopt a subarea plan for the light rail station area, and the failure to comply with housing related countywide planning policies.”

Shelter, Transitional, Emergency, and Permanent-supportive or “STEP” housing is an umbrella term encompassing an array of housing options for people exiting homelessness, ranging from emergency shelters to permanent supportive housing with wrap-around services.

“The Eastside has seen huge growth in housing demand in the last 20 years, causing prices to soar,” said Kian Bradley, one of two Mercer Island residents joining Futurewise on the appeal. “Mercer Island is incredibly well positioned to handle this demand, situated between two large cities, connected by light rail, offering access to excellent schools. It’s disappointing that the city continues to drag its feet and fail to meet the minimum requirements of the Growth Management Act.”

This is the first appeal filed as part of updates to local Comprehensive Plans that were due in 2024 across the entire central Puget Sound region. But it also represents the first official challenge looking at any city’s compliance with new requirements around housing established by House Bill 1220, a 2021 law overhauling the way that cities are required to plan for future housing growth. As a result, the impact of any ruling in this case could be felt far from Mercer Island’s borders, and crystallize for many cities in Washington what the new requirements actually mean.

The Urbanist has been following Mercer Island’s attempts to comply with HB 1220’s frameworks, which — among other things — require cities to target their growth targets to the actual expected income levels of future residents. Zoning that allows single-family homes doesn’t cut it when a city is expected to accommodate lower-income residents who can’t afford those types of homes.

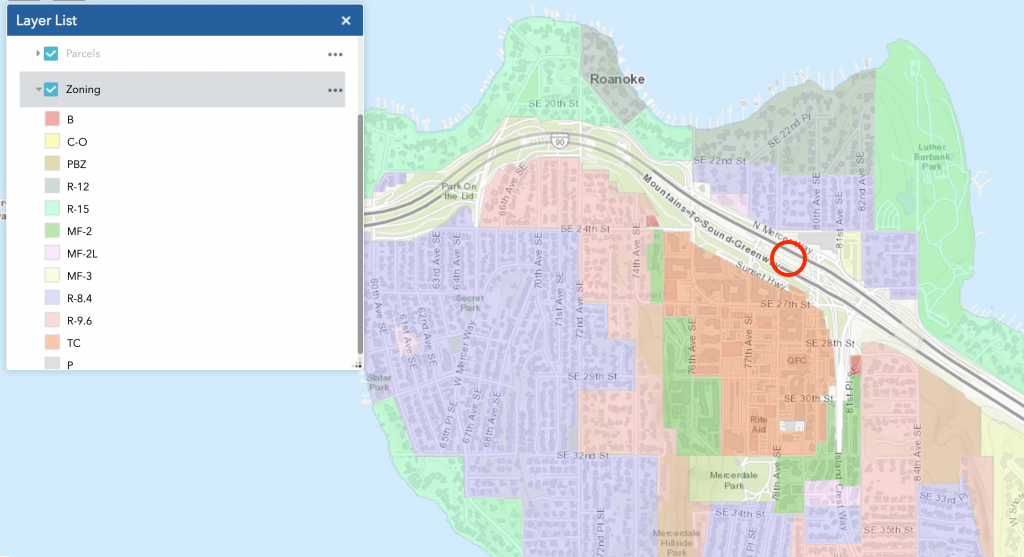

Mercer Island’s big move? Adding a few extra stories of housing capacity to a few blocks of its denser Town Center area, just south of I-90, with the tallest height limits allowed closest to the freeway trench. The City also added some of the strictest affordability requirements in the region, making it unlikely that any substantial development will materialize any time soon.

Outside the Town Center area, virtually nowhere else on Mercer Island allows multifamily housing, with minimum lot sizes in most residential zones varying from 8,400 to 15,000 square feet. That includes areas within a few minute’s walk of the new light rail station, set to open by the end of 2025 or in early 2026.

Futurewise’s Executive Director Alex Brennan told The Urbanist that Mercer Island’s efforts to comply with policies like HB 1220 have fallen far short of what’s laid out in state laws and the countywide planning policies based on those laws.

“They don’t have capacity for emergency housing, for example, to meet the emergency housing allocations they’ve been given,” Brennan said. “An important part of HB 1220 is that every city is required to remove a lot of the barriers to providing both that temporary shelter as well as permanent supportive housing for people that need that, and so Mercer Island is not meeting those requirements.”

Mercer Island is just three cities in King County that have declined to participate in a first-of-its-kind Comprehensive Plan review process conducted by the King County Housing Affordability Committee, a process that provided feedback to cities like Seattle over 2024 and 2025. Brennan noted that without receiving any county guidance, Mercer Island ended up incredibly out-of-alignment with county policies that require cities to prevent zoning intended for affordable housing to be concentrated in a small number of areas.

“They’re thinking that if they upzone in this one particular area, and have enough overall capacity that that’s enough, but it’s really not because they need to be looking at the station-area walkshed,” Brennan said. “It doesn’t have to be on every parcel throughout the city, but they need to be providing ways, that in different neighborhoods or different parts of Mercer Island, you can have multifamily housing that could conceivably be made affordable through the existing affordability programs we have, and they really they can’t just put all of that in the Town Center.”

Salim Nice, who has led the Mercer Island City Council as Mayor since 2022, has made himself a visible presence in Olympia, pushing back on some of the biggest moves that the state legislature has made in recent years with the aim of improving housing affordability. Nice testified against House Bill 1110, the sweeping 2023 law that effectively ended single-family zoning throughout most of the state’s urban areas, and more recently used the recent devastating wildfires in Los Angeles to argue against a bill that would reduce barriers preventing administrative lot splitting.

Nice has also pushed back on the Housing Accountability Act, which would more directly empower the state’s Commerce Department to find cities like Mercer Island out of compliance with state housing laws, including HB 1220. Now in its second year of consideration, the Housing Accountability Act just cleared its first hurdle of 2025, passing the Senate housing committee last week.

Without that law, the only mechanism for ensuring that cities are complying is making a case to the Growth Management Hearings Board, as Futurewise is doing in this case. In arguing against passing the Housing Accountability Act, Nice framed the issue as local decision-making versus top-down mandates, but a law passed by the state legislature without a clear enforcement mechanism is one that will clearly remain toothless.

“The [Growth Management Act] empowers local governments to tailor planning to their unique needs, ensuring community voices are part of the process,” Nice said at a January 24 hearing on the Housing Accountability Act. “Centralized housing compliance under the Department of Commerce strips away this local authority, replacing it with one-size-fits-all approach that ignores the distinct character of individual communities.”

The result of this new appeal will ultimately be a full illustration of whether or not Mercer Island has been using that local authority to shirk state law, in order to maintain its perch as one of the region’s most exclusive enclaves.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.