Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell’s proposed 20-year growth plan will produce more displacement, more greenhouse gas emissions, and increase the number of people living next to polluted roadways, compared to the “Alternative 5” growth plan preferred by city residents providing public feedback. And the plan would result in fewer apartments and condominiums built in the city, more hardscape and tree removal, and fewer housing units available to lower-income residents. That’s the conclusion presented in the newly released Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) on the One Seattle Comprehensive Plan.

The publication of the FEIS moves the proposal from the mayor’s purview to the Seattle City Council’s, which has started its review of the plan. The council has the opportunity to amend the plan, but early indications are mixed, with District 5 Councilmember Cathy Moore indicating that she would prefer less apartment zoning in the plan.

The 1,300-page document puts in sharp relief the differences between Harrell’s preferred plan and the “Alternative 5” option studied by the City in 2023 and supported by housing advocates as the most ambitious option officially on the table. Despite a significant push to go bolder with a grassroots Alternative 6, the Harrell plan instead retreats — a fact that was known, but not fully quantified until now.

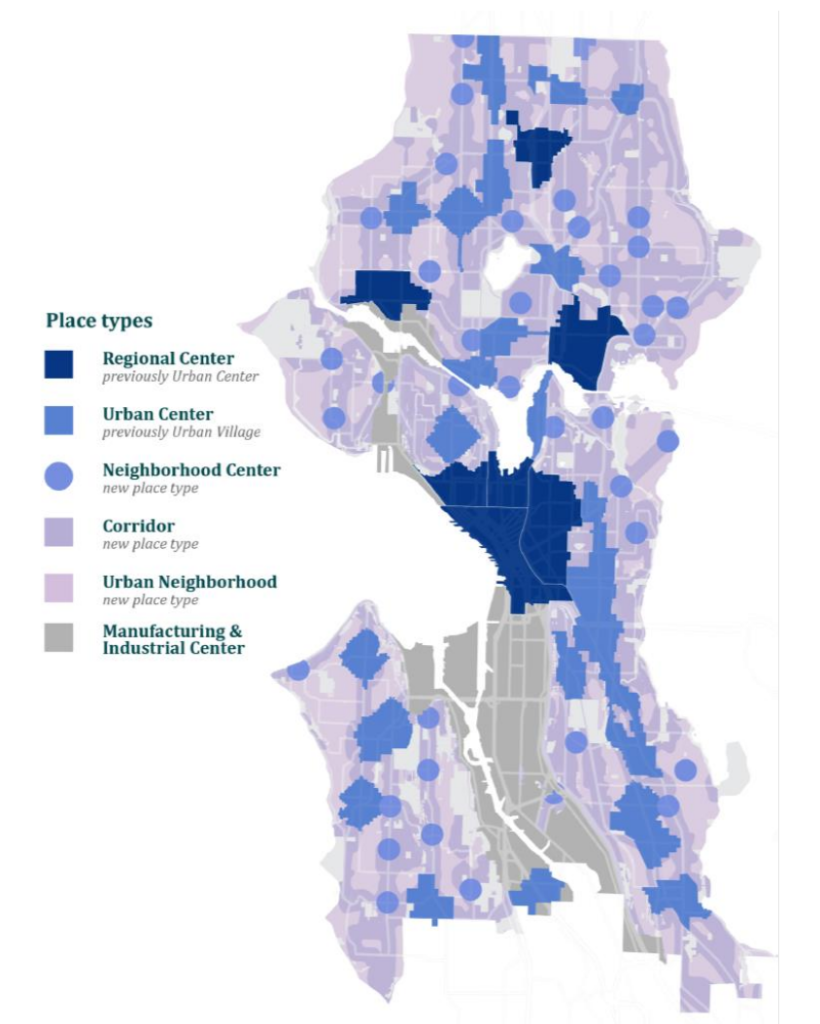

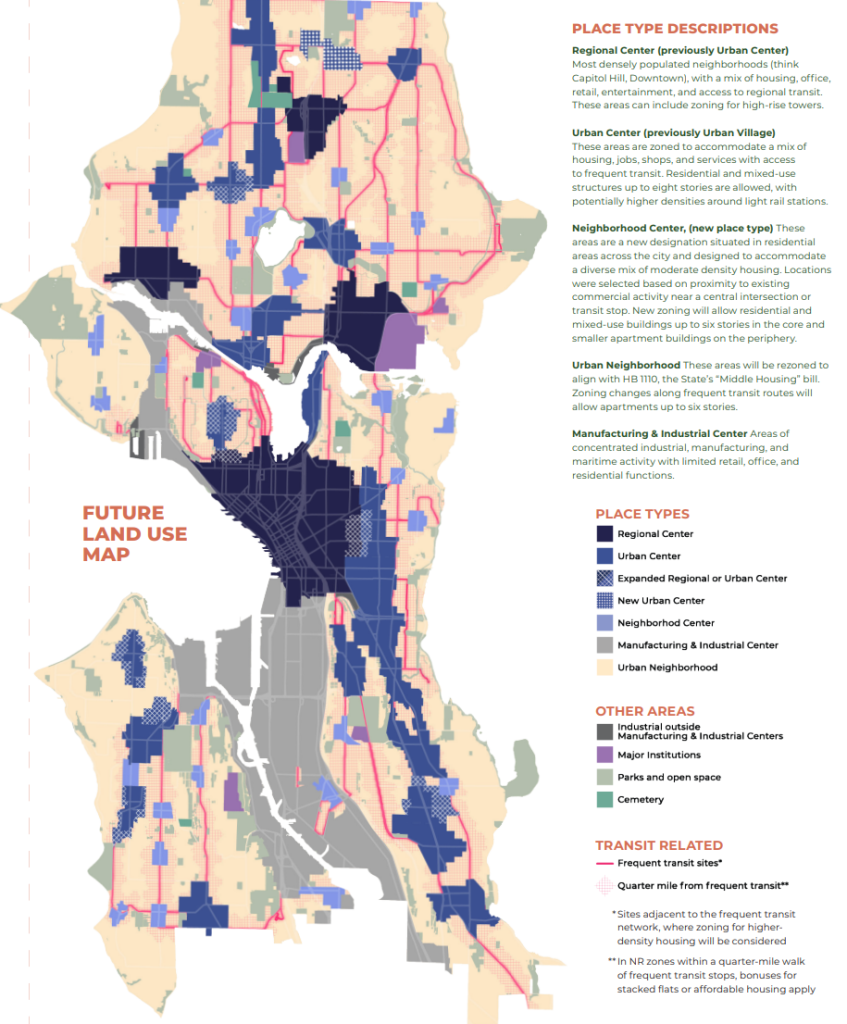

Simply put, Alternative 5 would have allowed denser multifamily housing to sprout up in many more places around the city. It would have included more “neighborhood centers” — proposed areas of focused growth and apartment zoning near existing commercial hubs in places like Tangletown, Madrona, and Highland Park. Alternative 5 would have also allowed denser housing in all residential areas close to frequent transit, including many places that larger apartment buildings have long been banned.

Instead, the Harrell plan removed about 20 neighborhood centers from the plan, including several with a significant potential to become community hubs, like Seward Park, North Capitol Hill and the Gas Works Park neighborhood in South Wallingford. But even more significantly, the mayor’s proposal narrowed the areas where apartment buildings would be allowed near those frequent transit lines, with major zoning changes only proposed directly along streets were buses run, leaving out other areas that are still a quick walk from a bus stop.

The Seattle Planning Commission, a city board tasked with reviewing any proposed land use changes in the city, called out this fact when it offered recommendations on the plan in December. “We are concerned about the current proposal to concentrate multi-family housing — the primary housing type that the City projects to be affordable to low-income households — along arterials,” the commission wrote. “This approach exacerbates health, safety, and livability impacts for people who live in the upzoned areas along arterials.”

The FEIS confirms that the Harrell plan would result in the highest number of new Seattle residents living within 1,000 feet of a major roadway, more than in Alternative 5. And yet, counterintuitively, it would also result in significant impacts spread across the entire city, by stepping away from density.

The same amount of housing — on paper

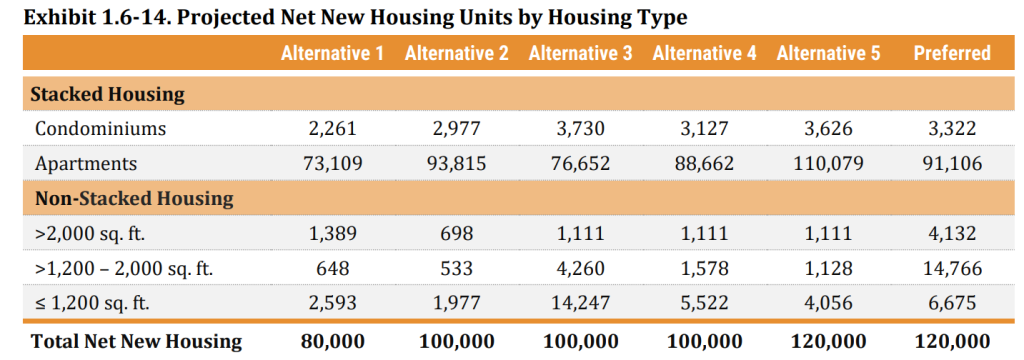

Both the Harrell plan and the set-to-the-side Alternative 5 outline a path for the city to add up to 120,000 homes over the next two decades. But the two proposals vary widely when it comes to how and where that housing would be added. The city expects to see nearly 115,000 new apartments or condominiums under Alt 5, but close to 20,000 fewer across the city under the Harrell plan. The difference would be made up in detached housing — largely townhouses — that takes up more land, and often have a higher price point than apartments or condos.

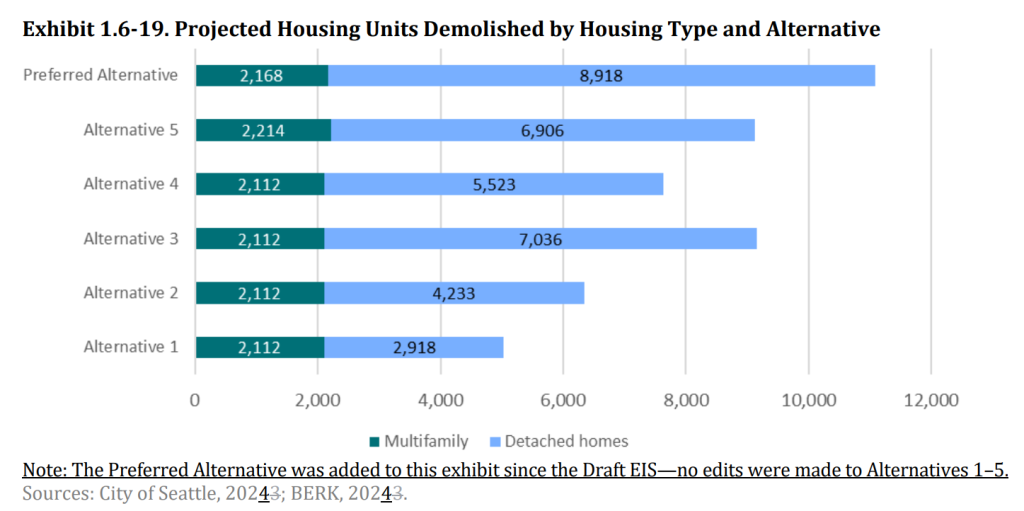

Combine that with a decision to continue mandating off-street parking even in some of the city’s most transit-rich neighborhoods, the expected amount of land expected to be redeveloped under Harrell’s plan would be 18% more than under Alt 5, with close to 2,000 additional housing units set to be demolished across the same city to add the same amount of housing. In contrast, under Alternative 5, more than 13 new dwelling units would be created for every one in the city that gets demolished, under Harrell’s plan that number would be less than 11, according to the FEIS.

When it comes to the issue of affordable housing — units subsidized for lower income tenants — the Harrell Administration’s plan also falls short. The FEIS projects over 3,400 fewer units to be produced via the city’s Mandatory Housing Affordability program, in which developers are required to either build affordable units on-site or pay the city to construct affordable units elsewhere. Given the early hand-wringing by some members of the Seattle City Council, including District 5 Councilmember Cathy Moore, that the plan doesn’t do enough to address affordable housing, this may become a point of contention as the council starts to review the plan in earnest.

And then there’s the fact that depending on middle housing — individual single family property owners redeveloping their properties to add four or six units — as a major way to increase the city’s housing stock over the coming decades could be a fraught proposition. It takes many more individual projects moving forward to translate to the equivalent of a large apartment building being built in a neighborhood center or close to frequent transit.

More driving, more hardscape, and more tree removal

The city’s modelling also expects Harrell’s preferred growth pattern to increase the amount of driving compared to Alternative 5, leading to more carbon emissions. “Transportation emissions from growth associated with the Preferred Alternative would be the greatest out of all alternatives and would result in increases in transportation emissions in comparison with existing conditions,” the FEIS states.

And then there’s the topic of trees. With so much focus on the potential loss of Seattle’s tree canopy as a result of future development, Harrell’s plan would result in more tree loss than Alternative 5, with only Alternative 3 — which targets just 100,000 units of net new housing — expected to result in fewer removed trees.

“Compared to Alternative 3 and the Preferred Alternative, Alternative 5 would direct less housing growth to areas currently dominated by low-density residential development,” the FEIS notes. “As a result, Alternative 5 may have a lower potential for vegetation impacts—including loss of tree canopy—compared to those two alternatives. Based on this criterion, the Preferred Alternative may have a lower potential for vegetation impacts than Alternative 3 but a higher potential than the other action alternatives.”

The ball is in the Seattle City Council’s court now

Now that the FEIS is out, a two-week window is open for a citizen or group to file an appeal, a process that has the potential to throw the entire council timeline around the One Seattle plan out the window. But an appeal isn’t a venue for a debate over policy questions to play out, and any appeal will have to clear a very high bar to force the city to go back and conduct additional analysis. Thanks to new state laws that have gone into effect in recent years, appeals might not gum up the works as much as past appeals, like 2018’s attempt to target Seattle’s nation-leading accessory dwelling unit (ADU) regulations.

But by the time any appeals work themselves out, the Seattle City Council will be faced with the policy question of embracing Mayor Harrell’s preferred growth plan, which leaves smart growth options like allowing apartment buildings near transit citywide out of the mix and instead focuses on sprawling townhouse development. Time remains for the council to change course for the mayor’s preferred plan.

Adding back neighborhood centers is an obvious place to start. In a meeting with the planning commission in January, One Seattle Plan Project Manager Michael Hubner defended the process to whittle down neighborhood centers, but also noted that the door is open for the city council to be able to add them back.

“It’s more than three-quarters of the centers that were studied that are actually in the final preferred alternative,” Hubner said. “But there were some choices made, working with the Mayor’s office on the final proposal on neighborhood centers. They are not all created equal, they have different strengths and challenges. What we wanted to do in the EIS was provide choice: choice for the Mayor, choice for the Council in different locations, and it was a process we always anticipated doing.”

While there has been significant push back on the idea of creating neighborhood centers, from residents in places like Maple Leaf, West Green Lake, and Madrona, the council as a whole will have to weigh those complaints against the benefits and the impacts spelled out in the FEIS. Ultimately that report makes it clear that it’s dense housing that checks all of the boxes when it comes to reducing environmental impacts on the city and achieving citywide goals around tree canopy, greenhouse gas emissions, and affordable housing.

The Seattle City Council is holding a public hearing on the proposed One Seattle Plan this Wednesday, February 5, at 5pm. In-person commenters will be prioritized between 5pm and 7:30pm, with on-site child care available, followed by testimony from commenters calling in by phone. Online sign-up to provide phone testimony will open at 4pm that day.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.