Seattle is in the midst of its once-a-decade periodic update to the Comprehensive Plan, which lays out a growth strategy for the next 20 years. Through the vagaries of the state Growth Management Act (GMA), Seattle’s growth target is set by King County, apportioning the countywide target it receives from the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC). That 20-year growth target for Seattle ended up at 112,000 homes.

One big question looming over Seattle’s whole Comprehensive Plan process is whether that target is high enough. To meet its goals around affordability and environmental sustainability, is Seattle aiming to add enough housing? Demand remains high to live in Seattle, and failing to meet that demand would push housing prices climbing even higher. The suburbanization of working families, meanwhile, contributes to longer commutes, exacerbating both traffic congestion, climate pollution, and household expenses.

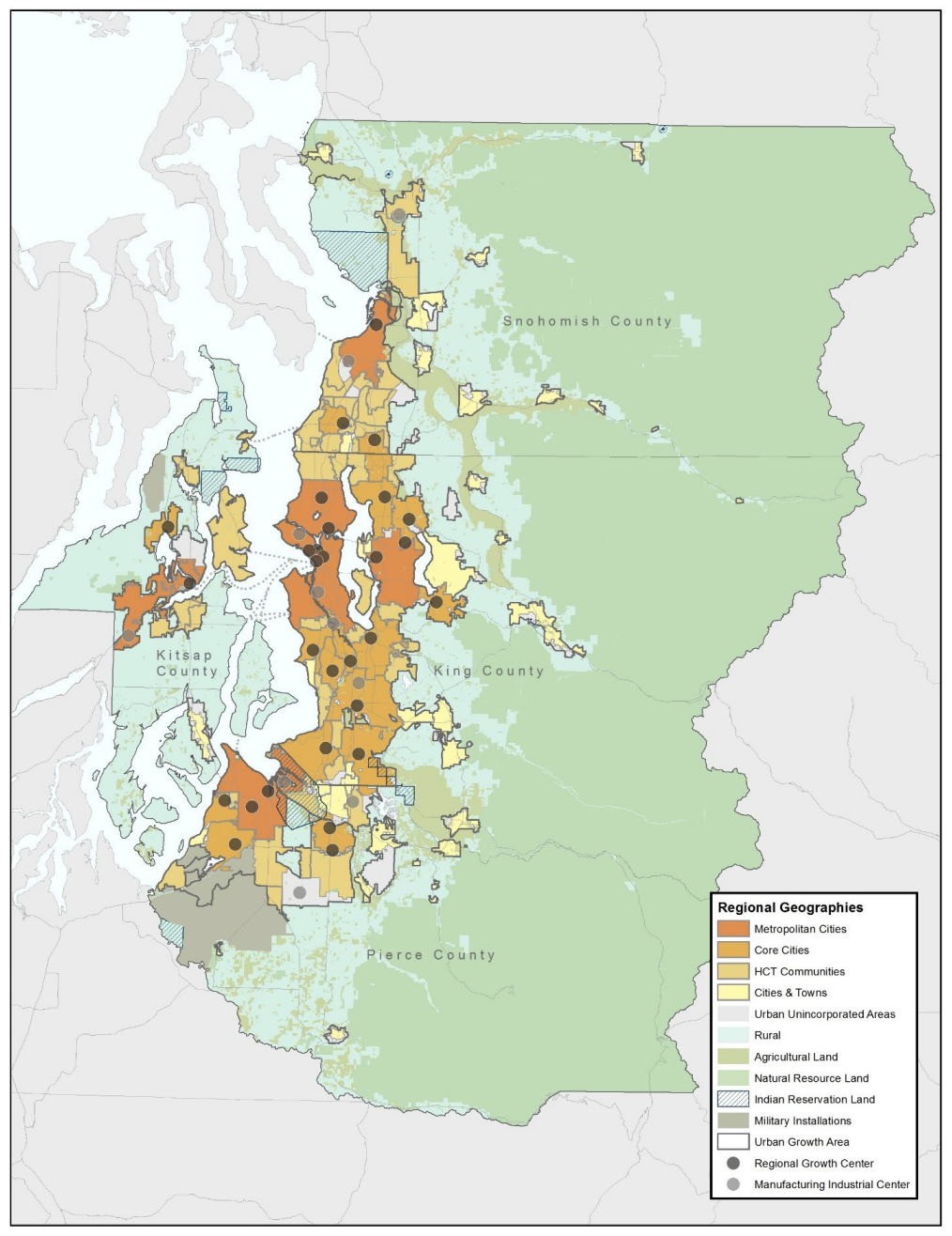

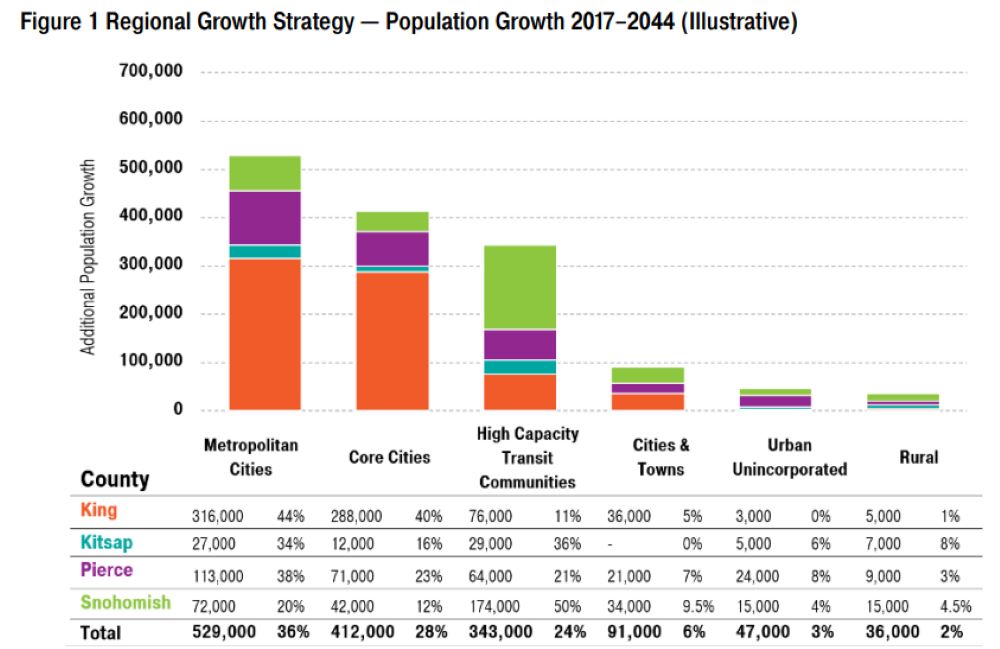

The greater Puget Sound region is expected to grow rapidly over coming years, adding 1.8 million residents by 2050 and growing from 4 million to 5.8 million, according to PSRC projections. Meanwhile, if Seattle maintains its average of two residents per household, adding 112,000 homes would mean roughly 224,000 additional residents.

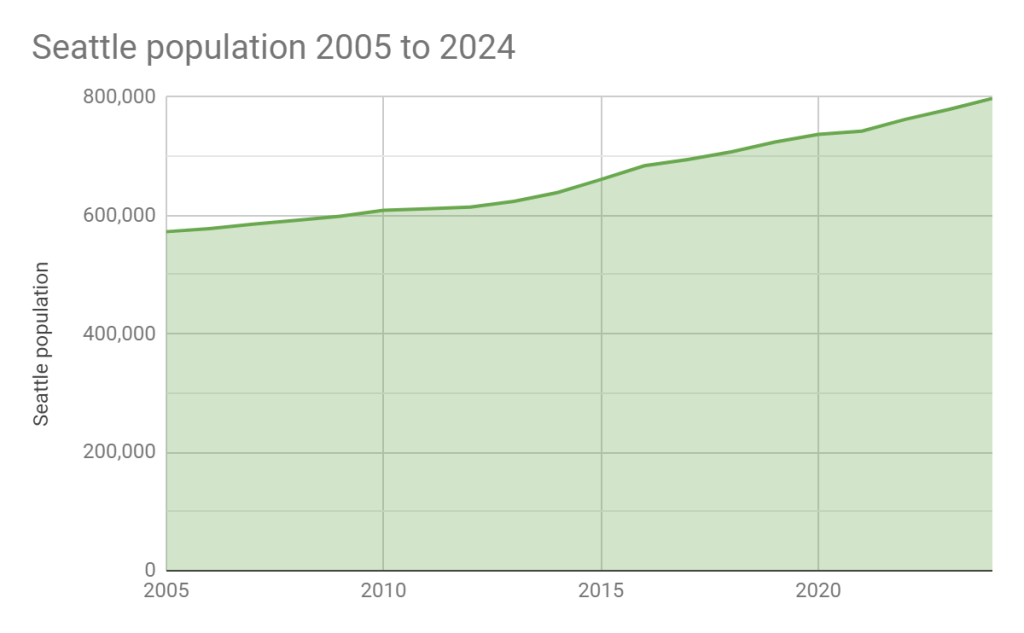

Seattle has long outpaced planning projections

Since 2010, Seattle has taken 31.5% of the metro area’s growth. Those new growth targets would amount to only 12% of the region’s projected 2050 growth.

The population of the Seattle metropolitan area has increased by about 600,000 since 2010, with 189,000 of that population growth in Seattle itself. The Emerald City grew from just over 600,000 residents in the 2010 census to nearly 800,000 in last state estimate in April 2024. Seattle’s total accounts nearly one-third of metropolitan population growth.

If the trend of Seattle absorbing 31.5% of metropolitan population growth were to continue over the next 1.8 million in population growth, Seattle would add 567,000 residents instead of the 200,000 target that the regional planning apparatus has assigned it.

In other words, regional planners are expecting Seattle’s housing and population growth rate to decrease dramatically, particularly as a percentage of regional growth. On one hand, this would appear logical in a region building a 116-mile light rail system and hoping to foster transit-oriented development near new stations, many of which are opening in suburban cities in coming years.

On the other hand, Seattle will continue to have the best transit and highest walkability in the region, and a proven market for new private development, the strongest track record of funding and producing nonprofit affordable housing, and first to dabble in publicly-owned social housing. The expectation of a significant slowing of the relative growth rate of Seattle may not come to pass. Baking that into planning assumptions could be a mistake.

“I want to state how lucky we are to live in a city where so many people want to come and live here too,” said Seattle’s new citywide councilmember Alexis Mercedes Rinck last week at a Comprehensive Plan discussion focused on anti-displacement measures. “We are so lucky that folks want to come live in this vibrant, green that strives to be welcoming for all.”

Rinck noted that building less housing than population growth and demand required resulted in people competing for the same housing, bidding up the price, and pushing people out of housing and sometimes into homelessness.

Suburbs often falling short

Seattle exceeding its planning target for growth has been a huge part of the region meeting its growth target and sustaining the economic boom of the past decade. Many cities in the region have repeatedly missed their PSRC planning targets, with civic ambitions that outstrip builder interest or local demand — especially with many cities continuing to assume new residents want to live next to busy highways.

One of the classic examples of this “coming up short” phenomenon is Everett. Being the county seat of Snohomish County has not turned the city into an urban mecca with booming populations figures, despite bold plans on paper. The latest state estimate put Everett’s population at 114,800, just 11,781 residents more than its 2010 census figure. Nonetheless, the PSRC’s Vision 2050 sets a target of 72,000 additional residents for Everett by 2044.

Some cities have also not matched their growth targets (modest as they can be) to streamlined regulations and permitting process that would actually achieve it. Cities like Auburn, Tukwila, SeaTac, Burien, and Federal Way have long fallen short of their growth targets — sometimes due to intentional efforts to obstruct apartments.

Meanwhile, Tacoma’s growth has accelerated, surpassing 225,000 in 2024 — up about 27,000 residents from the 2010 census. However, the goal that the PSRC and Pierce County have set of adding 113,000 residents by 2044 could still be a stretch — even with a fairly promising zoning overhaul.

Regional planners seem to hope that cities like Everett and Tacoma will pick up the slack as the slowdown they’re anticipating (and arguably engineering) in Seattle happens. But it will entail a good number of cities growing a lot faster than they have at any other time in last few decades.

What’s the harm in low-ball targets?

Top officials at the Seattle Office of Planning Community Development (OPCD) have acknowledged that the growth targets may be low-ball figures, and Seattle may end up overshooting them by a wide mark. “Our target under the Growth Management Act is only 80,000. That’s probably a lowball number,” Hubner said when OPCD rolled out the City’s draft plan in spring 2024. Even 112,000 homes may be low-ball.

“So when we’re projecting 100,000 units for the next 20 years are at least accommodating that as a baseline,” Quirindongo said back in spring 2024. “We know that that’s going to accommodate more than 200,000 people. And what we know is if we look at what the Puget Sound Regional Council told us — ‘you must provide this many houses’ — we actually have been providing more than that baseline. And it just so happens that our job growth has also exceeded the Puget Sound Regional Council original projections. So we’re just trying to keep up with ourselves.”

As The Urbanist‘s coverage touched on at the time, 120,000 net new homes over the next 20 years targeted in Alternative 5 and in the mayor’s preferred plan may sound impressive at first glance; however, that pace of 5,600 homes per year is actually significantly slower than what Seattle has maintained over the last decade. In fact, Seattle has built nearly 10,000 homes per year, on average, over the past seven years, according to the City’s housing dashboard. Oddly, the Comprehensive Plan anticipates a slower pace of growth despite zoning changes intended to encourage homebuilding.

Seattle can aim higher

Seattle officials could have said: “Well, we’re averaging nearly 10,000 homes per year already; why don’t we assume that continues apace, and set our 20-year planning target at 200,000 homes.” But that’s not what happened.

Seattle’s planning heads did take pains to note that planning targets are not meant to be limits, and that Seattle could well exceed them significantly — as the city did in the last planning cycle. However, slow growth advocates and critics of the mayor’s plan are all too happy to use low-ball growth targets to argue their neighborhood doesn’t need zoning changes since existing zoning capacity appears sufficient to meet the planning estimate.

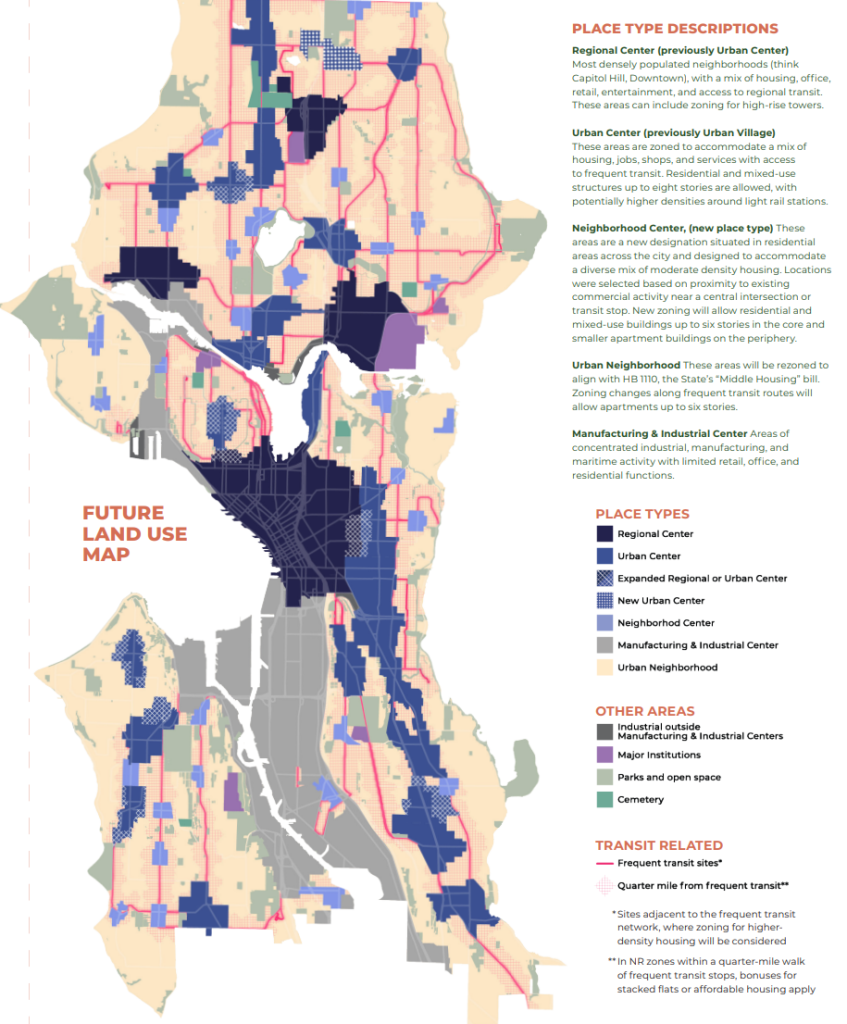

Housing advocates — including Share The Cities, Real Change, The Urbanist, and Tech 4 Housing — pushed for Alternative 6 during public comment for the draft “One Seattle” growth plan. Alternative 6 set a 20-year growth target of 160,000 homes, paired with the upzones that would have made that achievable. Instead, the City has hewed to the planning targets from on high and kept zoning changes more incremental that even Alternative 5 envisioned — despite Alternative 6 and Alternative 5 (the next boldest option) garnering the most support during public comment and having the backing of a broad alliance called the Complete Communities Coalition, which ran the gambit from nonprofit homebuilders to The Urbanist to the Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce.

Instead of upzoning to allow midrise apartment buildings everywhere within a five-minute walk of frequent transit — as housing advocates and the Seattle Planning Commission recommended — Mayor Bruce Harrell opted to propose only the immediate block along transit corridors, which are often on loud, polluted arterial roads. That’s going to put more new apartments in undesirable, polluted locations, rather than on quieter, greener side streets.

In shrinking the transit corridor upzones and trimming half of the new “neighborhood centers,” Harrell’s team overruled the City’s own planning department, as reporting by The Urbanist revealed. The move greatly restricts the new places where apartments could be built, limiting opportunities for working class renters. Instead, the mayor’s plan hope to building about 20,000 more townhomes and accessory dwelling units than under Alternative 5 — which could be a tall order given how slowly single family homes turn over and hit the market.

Meanwhile, several slow growth groups and homeowner associations have conflated housing capacity estimates with growth targets — in some cases purposefully to muddy the waters. For example, the Wallingford Community Council recently emailed its membership to oppose local zoning changes and paint the plan as a disaster for homeowners: “The Mayor’s plan […] surpasses the Comp Plan housing growth target by increasing housing unit growth to 330,000 housing units.”

Apparently, it needs explaining that if a city wants to grow by 120,000 homes in 20 years, its zoned housing capacity needs to be much higher than that since not every (or even most) parcels will turn over or redevelop in 20 years. To set zoning capacity exactly at the growth target would leave cities stuck in a position where they cannot hit their growth target until every single parcel zoned for additional capacity redevelops. This simply doesn’t happen in 20 years and is a recipe for sky-high housing prices and a severe housing shortage.

Hopefully, Seattle can still grow as quickly as it needs to grow to avoid pricing out the next generation of Seattleites and forcing additional environmentally-destructive sprawl to the suburbs. Setting a higher growth target and rezoning appropriately could allow the city to avoid rolling the dice.

Make your voice heard

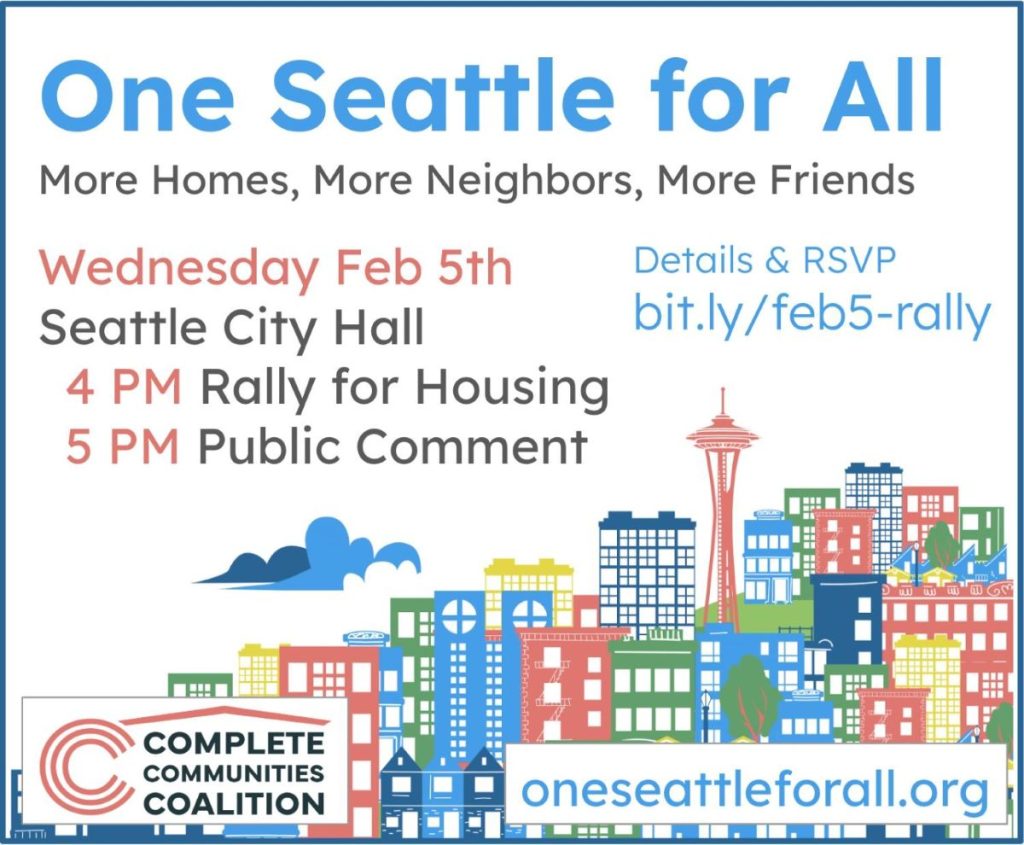

With the mayor’s proposal in hand, the ball is now in the city council’s court. Council has scheduled a public hearing scheduled for 5pm Wednesday, February 5 at Seattle City Hall. The Complete Communities Coalition is planning a rally at 4pm, shortly before the sign-up for public comment opens. Pro-housing advocates have also created a One Seattle For All petition tool to make contacting councilmembers easy.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.