The Seattle City Council has started its review of Mayor Bruce Harrell’s One Seattle Comprehensive Plan, but that work can’t fully kick off until the City of Seattle releases the final draft of the plan’s environmental review. Expected by the end of the month, the Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) puts a bow on the entire plan and allows the council to fully dig into the details of the plan’s “impacts,” including things like shadows from buildings allowed under adjusted zoning, projected transportation needs, and the degree to which the City expects to mitigate a changing climate over the plan’s 20-year time frame.

While the city is way behind schedule in having the council take this up, another potential roadblock looms ahead. The release of the FEIS sets the city up for an appeal of the plan’s conclusions. With a two-week window for appeal, there’s a narrow opportunity for a resident or group of residents to try and stop the plan from moving forward by alleging that the city missed something, or got something wrong.

Official public comment on the plan started in mid-2022 and extended through the end of last year. Now that the Comprehensive Plan has been delivered from the mayor to the Seattle City Council, public comments should be directed to councilmembers.

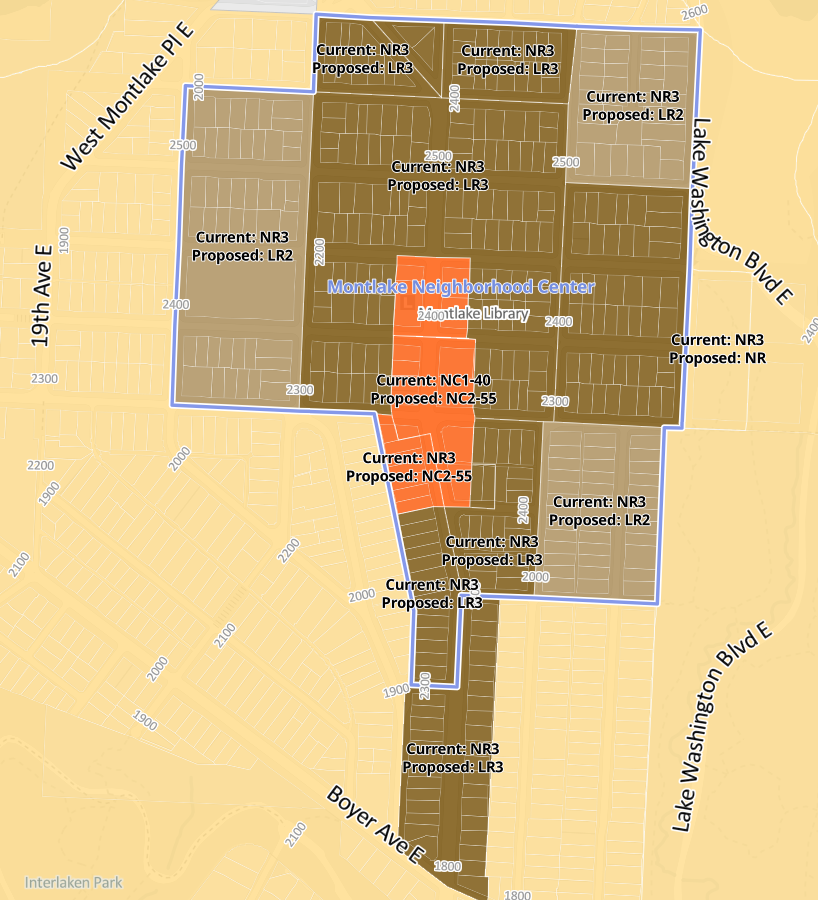

Opposition to the One Seattle plan has picked up steam over the past few months, in particular push back on a plan to create 30 new “neighborhood centers” — focused clusters of additional density at existing commercial hubs like Tangletown, Magnolia Village, and Montlake. An evolution of Seattle’s long-established growth pattern of focusing development in so-called Urban Villages, the neighborhood centers turned out much narrower in scope than many housing advocates had been hoping for, and only extend for a few blocks in each neighborhood.

Nevertheless, local opposition has been strong, with at least one group of residents in every council district starting a petition to get a neighborhood center scaled back or wiped off the map entirely. Many of the petitions use similar arguments around lack of infrastructure, including transit, and an alleged loss of neighborhood character that will come from allowing more apartment buildings. Residents, generally homeowners, from these same neighborhoods have shown up in numbers at the council’s two public meetings so far to discuss the plan, asking for councilmembers to amend the plan. In response, pro-housing petitions have also been started with the aim of preserving the neighborhood centers.

Appeals of zoning and land use changes made by the City are fairly common, and some of the biggest housing reforms in Seattle over the last decade have been followed by appeals — some of them lengthy. In 2017, a group calling itself the “Seattle Coalition for Affordability, Livability, and Equity” (SCALE) filed an appeal against upzones paired with the city’s Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program, and after losing that appeal, filed another with the state in 2019. Those zoning changes ultimately took full effect despite the appeal.

During that same time frame, the Queen Anne Community Council appealed legislation loosening restrictions on accessory dwelling units (ADU), contending that the new rules would have caused residents to “lose the very heart and soul of our city and our cherished neighborhoods as we know them.” That appeal was also ultimately dismissed, but it took more than six months to resolve.

Since those appeals, in the face of growing acknowledgement of the ways that land use appeals have been used to slow down development, the state legislature has passed a number of laws limiting the use of appeals under the State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA). Senate Bill 5818, which was signed by Governor Jay Inslee in 2022, limits appeals under SEPA for actions that local jurisdictions take to increase housing capacity and could limit the amount of time that an appeal spends at the city’s Hearing Examiner.

“It’s not a question of whether one happens or not — there will be a[n] appeal. And that’s automatic,” District 7 Councilmember Bob Kettle told Harrell’s planning staff at the council’s first meeting on the Comp Plan on January 6.

Kettle, a member of the Queen Anne Community Council before being elected to the council, clearly had a front row seat to that group’s appeal of ADU legislation, and he chastised Harrell Administration staff for not baking in time for the process to work itself out.

“That really should have been factored in as automatic as it relates to the state timeline,” Kettle said. “Whether one happens or not is not factual. There’s no doubt there will be one, we should just plan for it in terms of the timeline.”

While predatory appeals can have delay as a goal in-and-of-itself, changing the One Seattle plan to scale back zoning changes is likely the preferred outcome of any neighborhood group that will go through the trouble of hiring a land use lawyer. So what is the likelihood of the Harrell Administration being forced to walk back its proposal?

Tim Trohimovich is the Director of Planning & Law at the environmental nonprofit Futurewise and an expert on land use appeals, and he told The Urbanist that the odds are slim that an appeal would overturn the plan.

“That will fail,” Trohimovich said of an appeal.

On behalf of Futurewise, Trohimovich has successfully taken local governments to the state’s Growth Management Hearings Board and even the Supreme Court over actions that increase sprawl and harm the environment.

“The Growth Management Act requires the city to accommodate a population projection that is within the range of projections from the Office of Financial Management,” Trohimovich continued. “The King County countywide planning policies have set a minimum growth target for the city of Seattle. The City of Seattle has to plan to meet that growth target. So they’re required to meet that target. An appeal will not result in preventing growth in the City of Seattle.”

How much an appeal delays the process is, in part, up to the Seattle City Council and D3 Councilmember Joy Hollingsworth, the chair of the council’s Select Committee on the Comprehensive Plan. While the council can’t take a final vote on the plan until all appeals are resolved, the committee can continue to meet and hash out details and amendments while the city’s Hearing Examiner, who acts as a judge in the case of land use disputes, considers the appeal. But with Hollingsworth stepping in as a committee chair in the wake of former chair Tammy Morales’s departure from the council, an appeal could provide an impetus to put committee meetings on hold.

“We certainly don’t want to delay the process any further, but challenges to the Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) do have the potential to delay committee deliberations,” Joy Hollingsworth’s office told The Urbanist. “However, we have no way of knowing how significantly challenges to the FEIS will impact the Comprehensive Plan process until it is released. Our current plan is to continue convening Select Committee meetings until we get clarity on the number and magnitude of the appeals. There are a lot of unknowns at this point, but we’re working closely with the Office of Planning and Community Development, the Mayor’s Office, and Council Central Staff to keep any potential delays to a minimum.”

When it comes to some aspects of the Comprehensive Plan, time is of the essence. Washington State’s Growth Management Act required that a major update to the City’s plan to be adopted by December 31, 2024. If Seattle remains out of compliance, the city could become ineligible for state and federal grants, which have long been depended on as a source of transportation dollars.

But there’s an even more important deadline looming. House Bill 1110, the middle housing law passed in 2023, requires the city allow at least four units on every residential lot in the city — and includes a deadline of its own: Seattle, and other cities around the region, have to adopt specific code updates by the end of June. If they don’t, a model code created by the Washington Department of Commerce takes effect, superseding local zoning until such time as the City enacts compliant zoning.

The Harrell Administration is likely going to do anything it can to avoid this happening, to the point of proposing interim regulations that could bridge the period between the end of June and the final adoption of the plan.

“We would advocate to continue moving through the legislation and the plan, as proposed, even during the appeal period,” Christa Valles, Deputy Director of Policy in the Mayor’s Office, told the council earlier this month. “To the extent that those [appeals] get resolved in time to meet the state deadline, you will be better prepared to do that if we continue to meet throughout the appeal period.”

However, if an interim ordinance were to focus only on meeting the state fourplex zoning mandate, that could mean neighborhood centers would have to wait, delaying additional opportunities for denser multifamily housing that go beyond the state’s minimum standard.

While any appeal that’s ultimately filed has the potential to delay a citywide plan intended to increase housing affordability and create more vibrant, walkable neighborhoods, all signs point to those plans being able to move forward, no matter how many arguments get packed into that appeal. Whether the Seattle City Council will decide to water down the plan on their own — that’s a completely different question, and one that will play out in the coming months.

You can weigh in on the proposed One Seattle plan at a public hearing being held at 5pm at Seattle City Council chambers, as well as at the next meeting of the Select Committee on the Comprehensive Plan on January 29.

This article has been updated with a statement from Joy Hollingsworth’s office that had not been received by the time of initial publication.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.