Cities in Washington who don’t currently allow apartment buildings around their light rail, commuter rail, and bus rapid transit stops would be required to change their zoning to allow more housing to be built, if a bill introduced this week at the Washington legislature is successful. House Bill 1491, sponsored by Rep. Julia Reed (D-36th, Seattle), represents the third attempt to pass a transit-oriented development bill in three years, after the state Senate approved a bill in 2023 and the House approved one in 2024, but the two chambers ultimately couldn’t reconcile their proposals.

Getting a transit-oriented development (TOD) bill across the finish line has been touted as a central strategy to increase housing affordability in Washington, alongside policies like 2023’s middle housing law. But the fact that a bill wasn’t able to pass in an earlier year comes with a cost, in terms of timing.

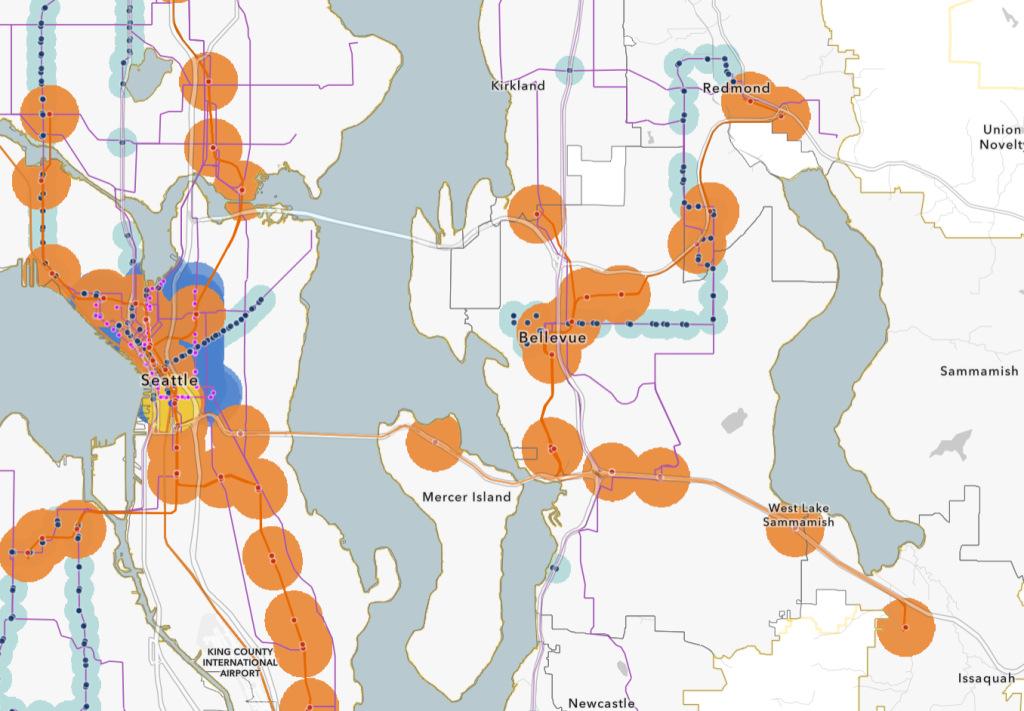

For most cities in the state that are part of a high capacity transit network — including everywhere Sound Transit operates — the bill would not go to into effect until the end of the decade, thanks to the state-imposed timelines for major updates to local comprehensive plans. Vancouver and Spokane, the only cities outside central Puget Sound with bus rapid transit systems, would be required to implement the bill first, in 2026, and essentially pilot some of the bill’s provisions.

In a conversation with The Urbanist before the bill was introduced, Rep. Reed framed the path to get to this point as less about tweaking policy and more about getting legislators on the same page.

“We’ve been working on this bill for several years, with a lot of stakeholders and the policies within it, I think, are very well baked at this point,” Reed said. “People really understand what’s in the bill, and a lot of it is sort of helping members get their arms around what’s in the bill, because it is quite a long and complex bill, especially if you’re not working in the housing space all the time.”

When fully implemented in Puget Sound, areas around Sound Transit light rail stations, Sounder commuter rail stations, and Seattle Streetcar stops would be required to allow larger apartment buildings, with areas around King County Metro RapidRide, Community Transit Swift, and Sound Transit Stride stations also required to upzone but not as dramatically. Public facilities and critical areas would be exempted, but that development capacity would have to be made up elsewhere within the station area.

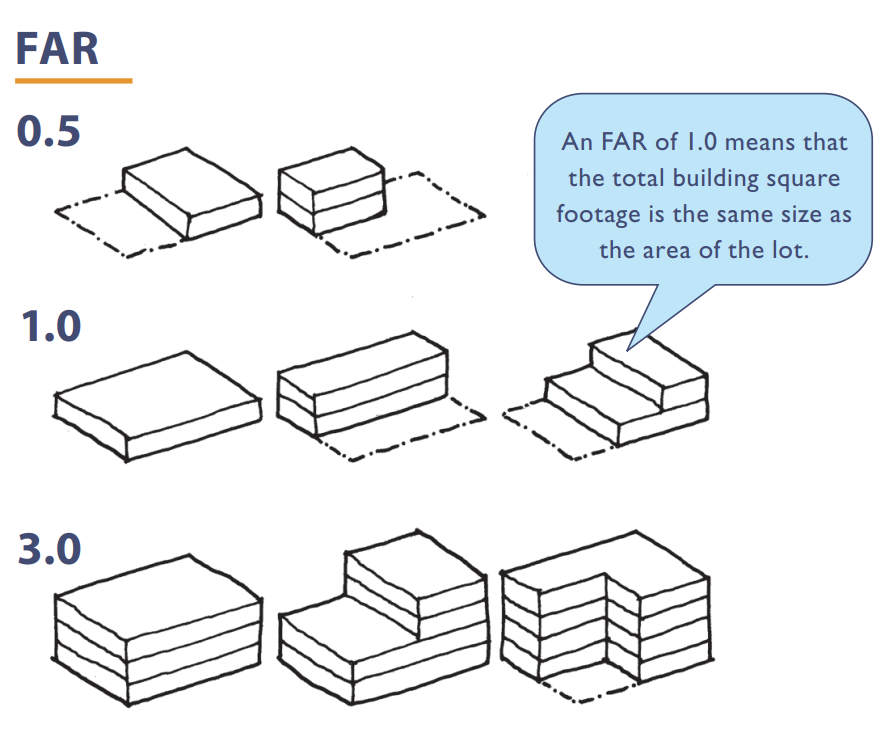

Under the bill, the requirement to allow density is determined by a measurement known as floor area ratio (FAR), which is how much floor space a building can take up on a lot. The higher the FAR, the more development is allowed. A one-story building taking up an entire lot has a FAR of 1, and a four story building taking up exactly half of its lot has a FAR of 2.

Cities would have to allow buildings with an average FAR of 3.5 within the entire half-mile zone around rail stops, a requirement that would likely lead to four to six story apartment buildings given the current economics of building construction. Cities could allow more density closer to the train station and less slightly further away, but the total would have to average out to 3.5 FAR.

Near bus rapid transit stops, buildings with an average of 2.5 FAR would have to be allowed — but a city can exempt 25% of those bus rapid transit stops, in which case an FAR of 3.0 would have to be allowed. The definition of BRT in the bill is tied not to the frequency of the line, but the its infrastructure, including “elevated platforms or enhanced stations, off-board fare collection, dedicated lanes, busways, or transit signal priority.”

The bill’s most controversial provision is a mandate for developers to set aside a certain number of units as income-restricted affordable housing, a policy known as inclusionary zoning (IZ) that many local cities around the state have already adopted. At least 10% of units have to be made available to people making 60% of a county’s median income — currently just over $72,000 in King County for a family of two — or at least 20% of units made available as “workforce housing”, defined as a household making 80% of the county’s median income.

An affordability mandate was not included in the 2023 transit-oriented development bill, sponsored by Sen. Marko Liias (D-21st, Edmonds) and approved by the Senate in an overwhelming 40-8 vote. Even with the departure of some of the Senate’s more moderate members after last fall’s election, the mandate is likely to remain a major sticking point on the bill this year.

Inclusionary zoning programs have been coming under increasing scrutiny nationwide in recent years, as they’ve become more popular with cities trying to find ways to incentivize affordable housing. While modest affordability mandates in high-demand locations can bring subsidized housing units along with significant amounts of new market-rate housing, if the mandate is set too high relative to demand for a specific housing market, they can stifle development.

“One of IZ’s fundamental shortcomings is that it does not address—and likely exacerbates—the housing scarcity that drives higher rents and home prices,” noted a 2024 paper by Shane Phillips, at the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies, looking at the potential impact of different affordability mandates on the housing market in Los Angeles. “It improves housing affordability for a few at the risk of worsening affordability for many, and it taxes precisely the activity needed to ameliorate the housing shortage and bring down rents: development.”

But Reed sees the removal of an affordability mandate from the bill as a non-starter.

“People, [including] some of the folks in the developer community, seem very anchored on this idea that I think is fantastical, that there is a realistic opportunity to pass a TOD bill with no affordability requirements, which, not only do I think it’s fantastical — no one has introduced that bill in the last two plus years,” Reed said.

“I’ve been happy in the background, asking, dare I say begging, the developer community to come to the table and talk about how we could do funded affordability and what that would look like for them, and what levers we could adjust to dial affordability to a workable level, to provide other offsets to the cost of adding affordability to projects,” Reed said. “And frankly, I just haven’t gotten any response. No one’s been wanting to come to the negotiating table. No one’s been wanting to talk about it.”

While HB 1491 is intended to ensure that cities are maximizing the area around their high-capacity transit stops, many of the cities covered by the bill have already moved to densify those areas and in many cases are going further than the requirements of the bill. In places where existing allowed allowed density meets or exceeds the requirements spelled out in the bill, the affordability mandate would not apply, keeping it from interfering with more ambitious local policies already in place. In Seattle, where the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) IZ program is already in place and requiring affordability of different levels across the city, those policies would also be able to stay in place as pre-existing, but cities could not add new IZ programs with a lower affordability mandate.

Senator Yasmin Trudeau (D-27th, Tacoma), who sponsored the Senate counterpart to Reed’s 2024 TOD bill, told The Urbanist that she’s not sure that the amount of effort that it would take to get this policy across the finish line this year is worth it, given the level of disagreement in the legislature around the affordability mandate. “For me, the issue is, what are we giving back to our constituents to say, we hear you, and we understand that housing affordability is a really big deal,” she said. “It’s just two ends of the spectrum that just keep butting into each other, and no one wants to have that conversation.”

Trudeau pointed to Shoreline, which has an inclusionary zoning policy in place, but also provides an incentive to developers that offsets the cost of the mandate, via the state’s Multifamily Tax Exemption (MFTE) program.

“If developers want to work with locals to unlock development capacity, there’s already local governments that are requiring affordability, like Shoreline,” Trudeau said. “I don’t want to spin my wheels mandating something that isn’t going to come into effect for five years, and that we’re not really prepared to do with the level of attention that I think is important to our people.”

Senator Jesse Salomon (D-32nd), a former member of the Shoreline City Council, also used that city as an example of affordability mandates needing to be fine-tuned for local conditions, in contrast with blanket standards that would apply everywhere in the state. “Once we got it right we saw a lot of development [in Shoreline],” he said. “You can put on paper whatever the hell you want, but if it doesn’t translate into real units, you didn’t accomplish anything. So I’m afraid that this conversation is stuck in an ideological component, not a technical component.”

The bill’s delayed implementation in central Puget Sound is also another reason why lawmakers may decide not to act this year, but there Reed also sees a potential silver lining.

“There will still be an opportunity to update the bill. There will still be time for cities to adapt,” Reed said. “And I think in a lot of ways it’s helpful if the state passes the bill in advance, because we do hear from cities how challenging it is to be working towards a certain framework with your Comprehensive Plan, and then to find out, ‘Oh, well, now there’s a new state law that we didn’t take into account a year ago when we started this process’.”

At first glance, Democrats in the House and Senate appear to be more united on this issue than ever. But time will tell whether that will translate to this complicated and substantive policy finally getting across the finish line, or whether things are more fractured on this issue than they initially appear.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.