This session, state lawmakers are grappling with major issues with education, housing affordability, and public safety, but structural issues with Washington’s transportation budget are also set to come to a head over the coming months. Thanks to declining revenues from sources specific to the transportation budget — like gas taxes — combining with rising highway project costs and major unmet needs across the state transportation network, hard choices are in store for legislators. They must not only craft a balanced budget for the immediate future, but also attempt to put the budget on a more sustainable financial path long-term.

The transportation budget crisis could turn into an opportunity for a reset, prompting budget writers to take a step back and evaluate whether the biggest projects in the state transportation budget — “highway improvements” that are largely focused on expanding capacity in the name of reducing traffic congestion — are the best investments for the state to be making.

On top of a budget gap to fill, the current maintenance backlog on existing state highways approaches $1 billion per year, with additional deficits facing ferry infrastructure and other state facilities. But so far, early signs indicate that state leaders are poised to double down on current priorities, even with few options on the table for new sources of transportation revenue.

Among those urging the state to change course had been Roger Millar, the outgoing head of the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT), who ended his nine-year tenure last week just as incoming Governor Bob Ferguson took office. Ferguson has appointed Julie Meredith, Millar’s assistant secretary for urban mobility and access, to head the agency, but in his final days on the job, Millar issued some departing warnings about the direction that state spending continues to head.

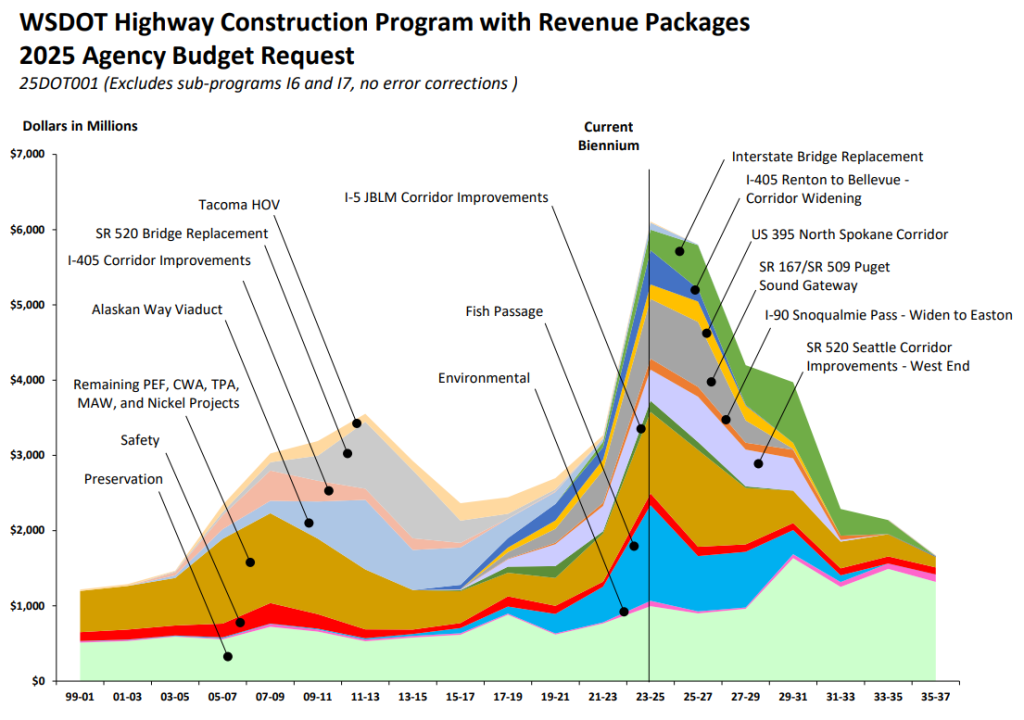

During his entire tenure, Millar was outspoken about the limited return on investment from expanding state highways through Washington’s urban areas, and the need to prioritize maintaining and preserving the system that already exists, while making it more resilient and safe. Last week, he gave one final presentation to the Washington Transportation Commission explaining why that shift is needed, noting that funding for highway improvements has always come first before other priorities in transportation budget negotiations.

“The paradigm currently is, ‘here’s our list of projects that we’ve committed to build — [the legislature’s] earmarked list. Fund that first and then what’s left? Well, we can put whatever’s left into operating the system, maintaining the system, preserving the system,'” Millar said. “That’s why in every budget cycle, maintenance is pushed out, preservation is pushed out, operations is not funded.”

That paradigm is also a primary reason that Washington’s complete streets mandate, which requires the state to close gaps in bike and pedestrian networks and make safety upgrades as routine maintenance and preservation work happens, has not been living up to its potential: funding levels have remained relatively low.

Millar pointed out that Washington’s population increased by over 35% in the past 25 years, and employment grew by over 39%, but the state only increased its highway network by 2.5% — at great cost to the state. “That suggests to me that the economy found it didn’t need additional highways to grow,” he said. “I think what the economy needed was reliable highways, and the reliability of our system is at risk today.”

“We have been expanding transportation capacity and adding to our infrastructure,” Millar said. “At this point in time, we desperately need to invest in our existing transportation infrastructure that has been neglected and is failing.”

Other states are starting to reassess their priorities, in large part due to increased awareness of the counterproductive impact that highway expansions have on their urgent climate goals. In 2021, Colorado passed a law requiring its department of transportation, along with regional planning organizations, to evaluate the individual impact of highway projects on emissions, a move that led to an expansion of I-25 through Denver being cancelled and funding instead being invested in transit instead. Minnesota is set to follow the same path, with a requirement that projects start to be evaluated this year, though the implementation details will matter greatly.

Though generally seen as a climate leader, Washington is not out-in-front on this issue, despite having had goals around reducing the collective number of vehicle miles traveled (VMT) within the state in place since 2008.

Earlier this month, at a pre-legislative session press event focused on transportation, both Sen. Marko Liias (D-21st, Edmonds) and Rep. Jake Fey (D-27th, Tacoma), the chairs of the legislature’s two transportation committees, tied to downplay the focus on expanding the highway system, in response to a question from The Urbanist about whether the state needs to “rethink the way we approach the transportation budget in terms of prioritizing expansion over maintenance.”

“I do want to push back on the idea that we’re expanding our system. You know, the expansion that we’ve seen in my community has been light rail,” Liias said in response, touting the fact that new riders on Sound Transit’s Lynnwood Link are creating capacity for drivers on I-5.

Lynnwood Link has been drawing people to transit, with ridership rising to record levels after the start of service last August, and creating a network effect for Community Transit’s Swift bus network.

But in addition to the newly completed widening of 196th Street SW in Lynnwood (State Route 524), which was able to get across the finish line thanks to state funding, WSDOT is currently moving forward on a slew of capacity expansion projects in Snohomish County. Those include a $123 million project to expand I-5 between Everett and Marysville, a $39 million project to add lanes to SR 531 in Arlington and a $47 million project to add another lane to SR 526, a road nicknamed the Boeing Freeway. And then there’s the US 2 trestle replacement, a megaproject that has been forced to take a back seat to others around the state, but which is expected to cost approximately $2 billion. Liias contends the state has other goals in mind when funding those projects beyond creating capacity.

“The highway projects that we’re doing aren’t about expansion, they’re about economic development, they’re about safety, they’re about freight mobility. You know, we have to serve multiple needs in this system,” Liias continued. “And Boeing needs to get their products to market. The ports need to get their product, agricultural commodities, to market. We all need to be safer. I think we need to sort of think about our system in the multi-dimensional way it has, and that’s what I continue to prioritize.”

Rep. Fey, who has served as the House’s transportation chair since 2019, also jumped in to argue that the state is less concerned with expansion.

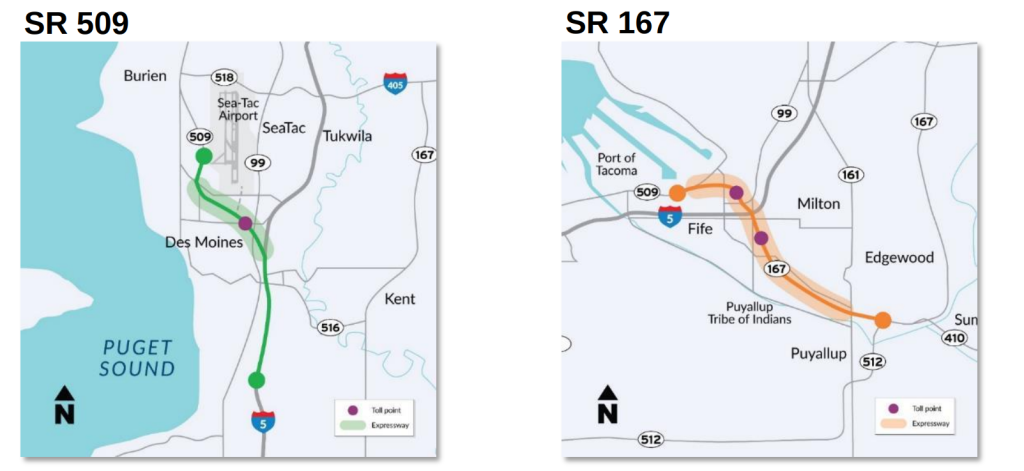

“I’m trying to get a project so that we can get goods from Eastern Washington into the Port of Seattle and Port of Tacoma, so they can compete in a worldwide marketplace,” Fey said, referencing the Puget Sound Gateway project, which is two separate highway extensions in North Pierce County and South King County.

Pegged at $2.7 billion, the SR 509 and 167 extensions will provide alternatives to I-5 for trucks from the two major regional ports via tollways.

“In addition, we’ve got a problem down where at any point in time could have failure with the bridge across Columbia River, one bridge of which is in a subduction zone,” Fey said. “So I wouldn’t call that adding to the system, nor what we’re going to have to deal with in the near, not that far future, right here at the Nisqually [River], where we’ve got some environmental problems and potential failure of the current I-5 bridge through the Nisqually. That’s not expansion, so it’s a balance.”

The so-called Interstate Bridge Replacement (IBR) across the Columbia is set to expand I-5 along a five-mile stretch on either side of the Washington and Oregon border by two lanes in each direction, replacing seven separate interchanges. Its $6-$8 billion cost is set to make it the single most expensive highway project in Pacific Northwest history, and sustainable transportation and environmental advocates have argued for right-sizing the project to focus simply on the two river crossings.

Last year, Washington and Oregon finally published the project’s environmental analysis, a document that ignores the impact of induced demand in its rosy projections of congestion relief. The IBR’s well-funded project team has long contended that it’s not adding real capacity because the new lanes are “auxiliary lanes” for drivers to use when merging, and yet those new lanes are expected to speed up traffic and reduce congestion, clearly making them expansion projects.

As for I-5 at the Nisqually River near Olympia, the state is proposing to move forward with adding a lane in each direction, for high occupancy vehicle (HOV) traffic, when it replaces the hastily-built highway bridge that was constructed in the 1960s. That’s despite the fact that an initial analysis on options for the corridor, completed with the Thurston Regional Planning Council in 2020, gave that option “the most negative score possible.” But adding an HOV lane is seen as a compromise measure in the face of pressure to go even further.

“There are people in Thurston County who have been advocating since before I became secretary for widening Interstate 5, from [Joint Base Lewis McChord] all the way to Tumwater,” Millar told The Urbanist in a conversation last summer. “What we’ve been able to do as a team is keep that expansion HOV lane, as opposed to a fourth general purpose lane. We could solve the problem of the river with a new six-lane facility [the existing size of the highway]. There’s a lot of pressure to make I-5 an eight-lane facility. That pressure is not coming from the DOT.”

Rather than debating which highway projects are and are not actually “expansion” projects, Washington could require they be evaluated for their climate impact, a move that would likely jeopardize prized and long-planned projects within legislators’ districts. But with the looming budget crisis, sticking with the status quo doesn’t really seem like an option. And trying to do so would likely be bad news for the state’s goal of eliminating serious and fatal traffic crashes by 2030, as well as the state’s ambitious climate goals, which call for a 45% reduction in emissions below 1990 levels by 2030. The first step is admitting that there’s a problem in the first place.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.