The voters of Washington State have reaffirmed a mandate to decarbonize the state’s economy, but one area that is often overlooked is freight. Washington voters rejected Initiative 2117’s effort to repeal the Climate Commitment Act (CCA) and backed Democrat Bob Ferguson for governor and Democratic majorities in the state house and senate, who have pledged to continue to implement the CCA.

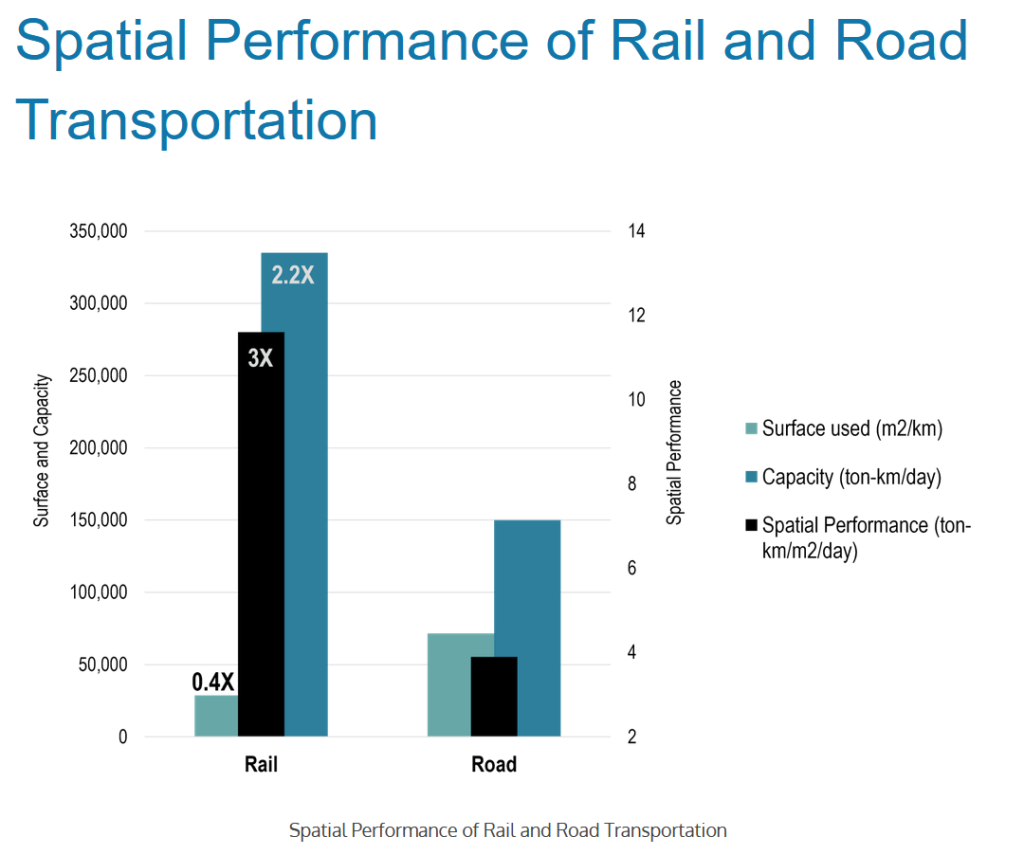

Transportation generates more greenhouse gas emissions than any other sector of Washington State’s economy, and simply switching the current system onto the electric grid won’t solve its fundamental issue: inefficiency. Automotive modes of transportation are both less-fuel efficient and more land-intensive than rail, whether that rail is electrified or not.

Thousands of passengers can glide down a single rail track during rush hour, and thousands of freight tons can do the same at night. Thousands of parking spaces can be condensed into a couple centrally-located rail platforms, and hundreds of square miles of paved surfaces at truck facilities can be replaced by a couple rail yards serviced by electric trucks and vans to cover the last mile. All this density could be accomplished even while decreasing local air pollution, because a single train, whether diesel or electric, can take thousands of cars and trucks off city streets, opening valuable urban space to pedestrians, parks, and amenities.

The Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT), Sound Transit, and local transit agencies have recognized this issue for passenger traffic, but the state seems to have ignored inefficiencies built into its current freight logistics network. Instead the state has generally guided investment toward truck routes rather than upgrading freight rail.

Due to the private ownership of Washington State’s main rail corridors, electrifying the system has barely entered the conversation, despite the potential long-term pollution and decarbonization benefits. In an interview with The Urbanist, state senator Marko Liias (D-21st, Edmonds), who chairs the transportation committee, pointed toward lower hanging fruit.

“[Rail electrification] is really hard because we don’t control the right of way on the mainline. In order to electrify the Cascades, it would require us to make substantial public investments in the private infrastructure,” Liias said. “There’s lower-cost quicker return opportunities that we’re going after first. Obviously, 50-100 years from now it will all be decarbonized, but the Burlington Northern infrastructure is not on the path to be one of the early movers on that.”

Fortunately, the state and federal government have been focusing on how to increase the efficiency of passenger transportation with rail in Washington, as exemplified by the electrified Link light rail expansions, the acquisition of new trainsets on the Cascades line, and improvements to Seattle’s Amtrak rail yard.

“In our state, passenger rail is more the place where people are trying to think outside the usual paradigm, whether it’s light rail, Cascades or high speed rail, to create that people-moving capability on rail,” Liias said. “That hasn’t yet in the same broad widespread way caught the imagination in the freight space.”

This is an oversight, but an understandable one, since people experience their commutes first-hand, but rarely interact with freight logistics. People feel the pain of bumper-to-bumper traffic or sticker shock at the gas pump and wish for a better way. This is how public transit projects can earn the loyalty of constituents by directly improving their mobility and the financial and carbon efficiency that improves their bottom lines.

Meanwhile, freight inefficiencies are less visible to the public, as the intricacies of supply chain management are mixed into the myriad factors which affect price and profitability. Nevertheless, the hidden nature of these inefficiencies do not exempt them from the state’s prerogative to decarbonize.

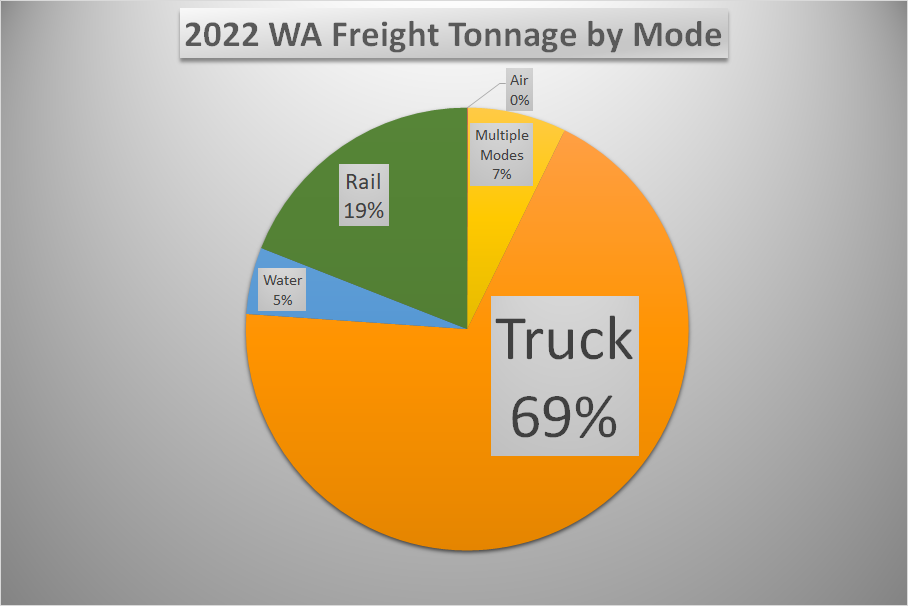

Freight rail is three to four times more fuel efficient than trucking, WSDOT spokesperson Janit Matkin said. While electric locomotives are ideal, switching from trucking to diesel locomotives would still realize the fuel efficiency gains Matkin provided because of rail’s innate efficiency advantages over trucking. As the scale and distance of freight logistics increases, the inefficiencies of trucking compound regardless of whether the vehicles are diesel or electric: more engines per-load, the friction of tire-on-asphalt traction, more paved space at freight terminals, etc. Currently, rail’s potential remains unrealized, as trucks carry 69% of the state’s freight by weight, despite their lower efficiency.

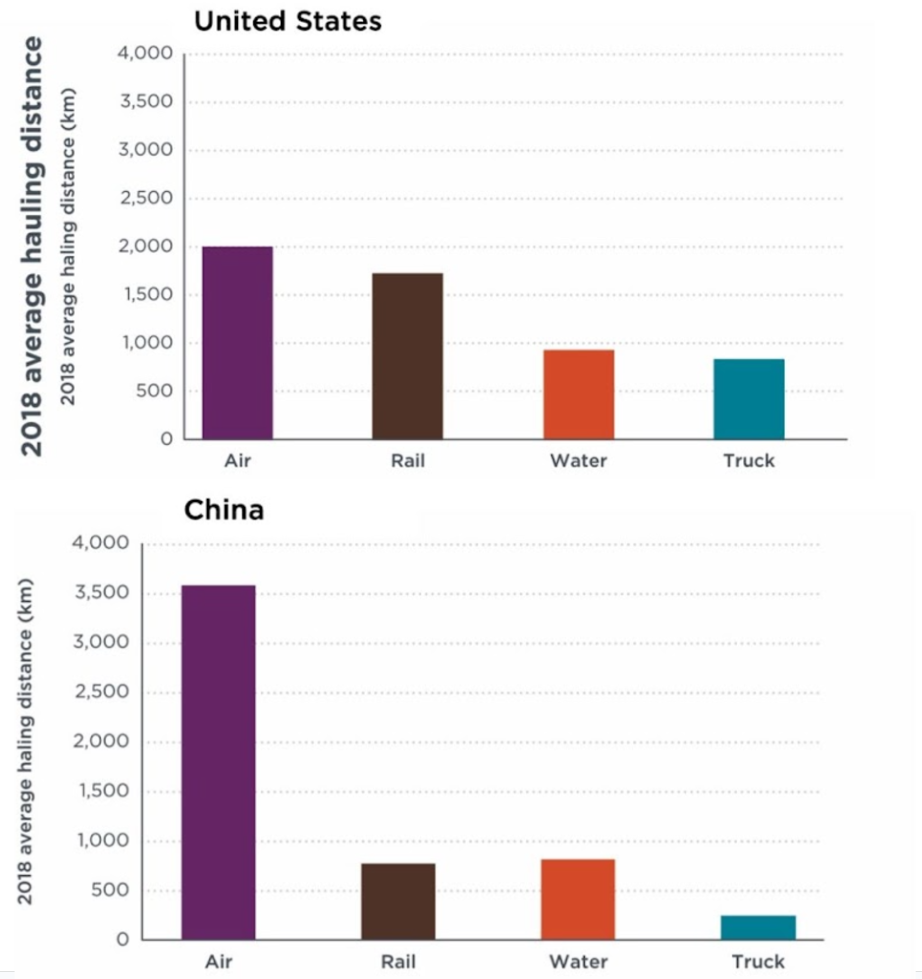

The American overreliance on inefficient trucking stems from its long-standing policy of investing in roads as public infrastructure while abandoning rail to the private sector. This has caused rail companies in the United States to prioritize the most productive markets, with the profit-first approach narrowing companies’ focus to only those few sectors where rail is most lucrative (long-distance low-value shipping). This has allowed trucking to capture long-distance shipping which rail could perform if its infrastructure were provided by the state.

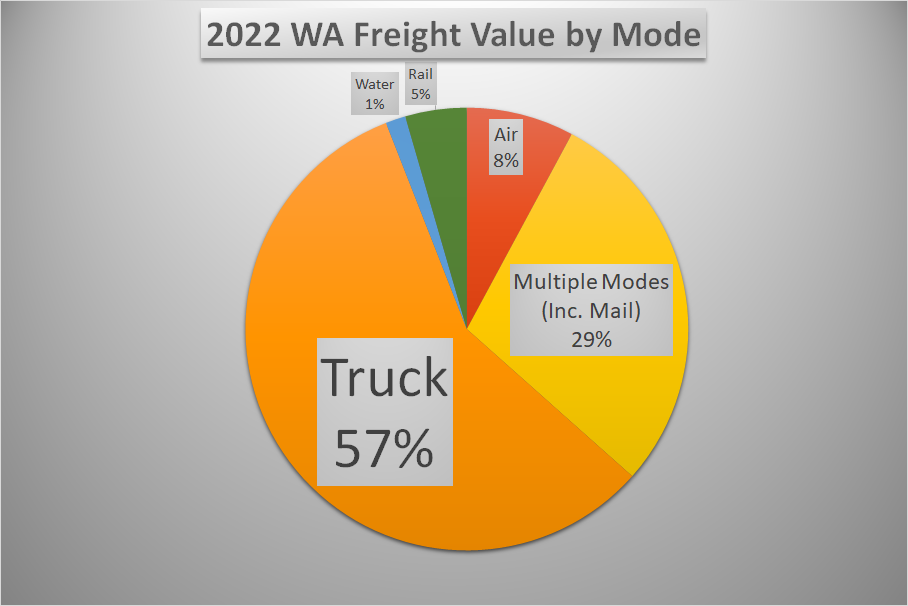

Forestry products, agriculture & seafood, energy, and industrial manufacturing are all sectors where rail would provide a more logical alternative to trucking. As consumer goods are also increasingly transferred between large terminals and warehouses, rail has the potential to capture even medium/high-value cargo from trucking. (Graph by Collin Reid, data by Washington Commodity Flow Dashboard)

Notice how high-tech manufacturing, clothing & miscellaneous manufacturing, transportation equipment, food manufacturing, and last-mile logistics all have greater value than weight. While ideally every form of cargo would be transported by the most efficient systems, it’s at least logical from an effectiveness standpoint to have trucks transport goods whose increased value justifies decreased efficiency. (Graph by Collin Reid, data by Washington Commodity Flow Dashboard)

Failing to see rail as a public asset has also sabotaged the state’s capacity to capitalize on modern logistical trends. According to ranking Republican on the House transportation committee Andrew Barkis (2nd LD, Lacey), Washington’s logistics network is centralizing around major terminals and warehousing facilities, the exact niche rail specializes in serving.

“Commodities come in on a ship, you have a limited amount of capacity at the ports, so they move that, and then what they can do is they can move it in bulk to another area and then distribute it from there,” Barkis said.

Establishing rail connections between ports, warehouses, and distribution centers would capitalize on rail’s land-use advantages, as fewer lanes and paved facilities would be necessary to transport the same amount of goods. At the consumer-end, smaller electrified road vehicles could cover last-mile logistics better than point-to-point long-haul trucking.

While the state has yet to realize this potential to its fullest extent, recognition of rail’s essential role in the agricultural sector has led to concrete results: grain trains and the state-owned Palouse River and Coulee City (PCC) short-line rail system.

Grain and energy (usually coal and oil) are logical for transportation by rail, as they are medium/low value, heavy, and not time-sensitive. Still, that doesn’t mean high-value time-sensitive industries are unable to capitalize on the efficiency of rail to avoid sacrificing profits on inefficient transportation modes. (Graph by Collin Reid, data by Washington Commodity Flow Dashboard)

Rail is more than capable of delivering increased profitability to high-value industries by increasing the efficiency of freight logistics. Expanding short-line networks and rail terminal facilities would increase its competitiveness with trucking. (Graph by Collin Reid, data by Washington Commodity Flow Dashboard)

The PCC in particular is something both Liias (a Democrat) and Barkis (a Republican) acknowledged has been a tremendous success. This is a state-owned short line rail system where operations are leased out to small private carriers, and it’s proven essential in supporting the viability of grain farming in eastern Washington. The inefficiency of trucking makes it cost prohibitive for long-haul grain shipping, to the point that Mike Bagott from Palouse Grain Growers, a small grain co-op on the system, laughed when I asked about the viability of trucking.

“Long haul trucking grain all the way to Portland or Vancouver? That makes no sense,” Bagott said. “Forget about it.”

Liias, Barkis, and house transportation chair Jake Fey all acknowledged that investing in short-line rail across the state will be key to improving efficiency and meeting climate goals, expressing interest in supporting the expansion of short-lines throughout the state.

“The more near-term state role is to facilitate main line connections off of the main line into the industrial centers and freight corridors so we can move more freight more efficiently so we can reduce the cost and complexity of doing the mode transfers,” Liias said. “I think that’s probably more the near-term: how do we build that connectivity.”

Although support for short lines is both necessary and a welcome sign that policymakers are beginning to take freight rail more seriously, providing tax benefits to companies investing in rail infrastructure (as appears to be the modern policy prescription) likely won’t be enough to meaningfully improve transportation efficiency to the degree the CCA and the state’s climate goals requires.

“If we look at how we enhance our supply chain, I think incremental improvements in rail are front and center,” Liias said. “But full scale brand new corridors for freight, that’s not the kind of front-of-mind priority that’s expressed when I talk to folks on the ground. Because 70% of us in the state drive cars all the time, I think it’s natural and instinctive to think of it as a mode, we don’t broadly use rail yet.”

This is exactly why I’ve criticized the Puget Sound Gateway Project for seeking to establish a trucking connection between major port terminals and warehousing facilities when the state didn’t even investigate the feasibility of an upgraded rail corridor: people are repeating the mistakes of the past because they can’t imagine a world beyond the one that has been built around them.

Asked about the state providing rail infrastructure in the same way it currently provides road infrastructure between major warehousing and port facilities, Liias said that is not how things are typically done, with the government typically letting the private sector guide investment.

“That is a little beyond the traditional paradigm,” Liias said. “On the freight side in particular, it’s not necessarily in the state, but in the market place there’s still a preference for trucking and highway infrastructure for freight that’s just baked-in. If we look at the Gateway corridor between the Port of Seattle and Tacoma where there were connectivity challenges, the predominant request of the community and freight users was to build that highway connection.” While guiding freight rail planning may not be the role the state government has recently played, connecting large port terminals and warehouses via rail is textbook transportation geography.

Collin Reid

Collin Reid is an educator who moved to the Central District of Seattle in 2024 after having lived and worked in St. Petersburg Russia for eight years. His background in political science and international experiences led him towards urbanism and transportation as the foundational elements of society. He is a member of the Seattle Democratic Socialists of America.