The Harrell Administration is floating changes to the Multifamily Property Tax Exemption (MFTE) that housing advocates warn could cause the affordable housing program to “collapse entirely.”

In late October, the Seattle Office of Housing (OH) gave a presentation to apartment owners, developers, and property managers outlining proposed changes to the city’s Multifamily Property Tax Exemption (MFTE) program, which expires at the end of 2025 and has encouraged the construction of more than 7,000 affordable units in Seattle since it first went into effect in 1998. The program has been re-authorized by the city council six times, and OH’s presentation described proposed changes in the new version that will eventually be submitted to the city council for approval, known as Program 7 (P7).

The voluntary MFTE program exempts owners of multi-family housing developments from property taxes for 12 years (with an option to renew for an additional 12 years) in return for designating a portion of the units as income- and rent-restricted. The program was created as a tool to create middle income “workforce” housing integrated into market-rate apartment buildings and has traditionally served renters who make between 65% and 85% of average median income (AMI)

The response from housing advocates and developers to the Office of Housing’ proposed changes has been resoundingly negative.

In a November letter to OH director Maiko Winkler-Chin, the Washington state chapter of NAIOP, a commercial real estate development organization, wrote that the proposed changes “pose an existential threat to Seattle’s workforce housing industry.” NAIOPWA noted that “without immediate and substantial revisions, we are certain that participation in MFTE will collapse entirely, decimating what has been the city’s most successful vehicle for creating workforce housing units.”

Maria Barrientos, whose real estate development firm Barrientos Ryan has been building market rate and affordable housing in Seattle for 35 years, has served on many advisory boards for each iteration of MFTE. She said that every project she’s built – which tend to be focused in Uptown, Queen Anne, Eastlake, and Capitol Hill – has used the MFTE program. If the proposed changes go into effect, Barrientos said her investors will no longer fund projects in the MFTE program.

“In the past year to two years, the national developers – they fuel 50 to 60% of our development when we’re in a boom – have said they will not participate in this program anymore,” Barrientos said.

The NAIOPWA letter said that a mix of higher fees, lower AMI requirements, and continued bureaucratic burdens to prove renter qualifications threaten the viability of the program. Rather than improving the program, the changes will make things worse, they contend.

“Disappointingly,” NAIOPWA wrote, “the rest of the proposed program intensifies the dysfunctional aspects of Program 6 – and adds new operational requirements, extremely high program fees and drastically lower AMI thresholds that we believe render the program unusable.”

Ben Maritz, an affordable workforce housing developer (who also serves on The Urbanist’s board), said that the Office of Housing has lost sight of the program’s original partnership between the city and developers to build both market rate and affordable housing.

“I think the Office of Housing folks are smart and they’re trying to do their best,” Maritz said. “But they’re looking at it through this lens of: ‘we only care about affordable housing. We don’t care about market-rate.’”

The Office of Housing declined to comment on the proposed changes until formal legislation is submitted to city council later this year.

MFTE grew out of the state’s Growth Management Act, and began as a statewide program that encouraged cities to offer tax credits to real estate developers in order to boost construction of market rate and affordable housing. Many cities across the state, including Spokane, Tacoma, and Vancouver still use a variation of the state law’s formula: an eight-year tax exemption to promote new market-rate housing; a 12-year tax exemption for buildings that offer 20% of units to those earning below 115% AMI. Due to recent state-level reforms, the 12-year exemption is renewable for a second 12-year period and local jurisdictions can offer a 20-year exemption to buildings that offer 25% permanent affordable housing (run by a housing nonprofit) to households below 80% AMI.

The city of Bellevue, for instance, has a relatively simple MFTE calculation, giving 12-year exemptions in return for 20% of units affordable to people earning 80 percent AMI (with several minor variations that offer incentives for two-bedroom units).

Since its inception, the statewide program has resulted in 61,000 new units of housing, 11,000 of which are affordable, according to the Washington State Department of Commerce. The majority of those homes are in Seattle.

In Seattle, the MFTE program, in its six different revisions, has grown increasingly complex and more focused on providing units to renters at a lower band of AMI. As the city drives AMI levels down, the MFTE program increasingly overlaps with the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program, Seattle’s version of inclusionary zoning, which caps rents at 60% of AMI for affordable units.

Seattle does not offer an eight-year exemption for market rate housing, and in its current form, the MFTE program grants a 12-year property tax exemption to buildings in which 25% of units are made available at rents affordable for households that earn no greater than 65% of median income for compact and studio units, no greater than 75% of median income for one-bedroom units, and no greater than 85% of median income for two-bedroom and larger units.

Some of Seattle’s past changes to the state law formula were designed to encourage the creation of larger units, which are in short supply citywide. A statewide report in 2019 found that 75% of units created in Washington by MFTE were either studios or one-bedroom units.

Martiz, however, said that the city’s $970 million housing levy is a better way to address the shortage of two-bedroom and larger units.

“[The Office of Housing] is like: oh, we’re just going to tell people they can’t build studios under MFTE and then developers are going to all of a sudden go build family size, two bedroom units,” Maritz said. “That’s not how it works. If you say we can’t build the one thing that’s economic to build, guess what? We’re not going to build them.”

Currently, the fee for applying for Seattle’s program (which by state law can only be used to fund staff costs to administer the program) is $10,000 per project.

In addition, tenants are required to go through a complicated process to prove they fall under the AMI limits. “You have to fill out a set of paperwork that is significantly more onerous than a tax return to prove that you’re poor enough to be in that unit,” Maritz said. “And then you have to do it again every year.”

Barry Blanton, who owns a real estate management firm that processes paperwork for many MFTE units across the city, said that OH has added layers of bureaucracy to the program, making it “expensive and time consuming and invasive.” Blanton said the burdens of the program are increasingly discouraging those who earn below the required AMI level from applying. “Originally, yes, they had to qualify, but once they qualified, you kind of left them alone,” he noted.

According to OH’s presentation, the vacancy rate of MFTE units is currently 11%, with 38 buildings above 20%.

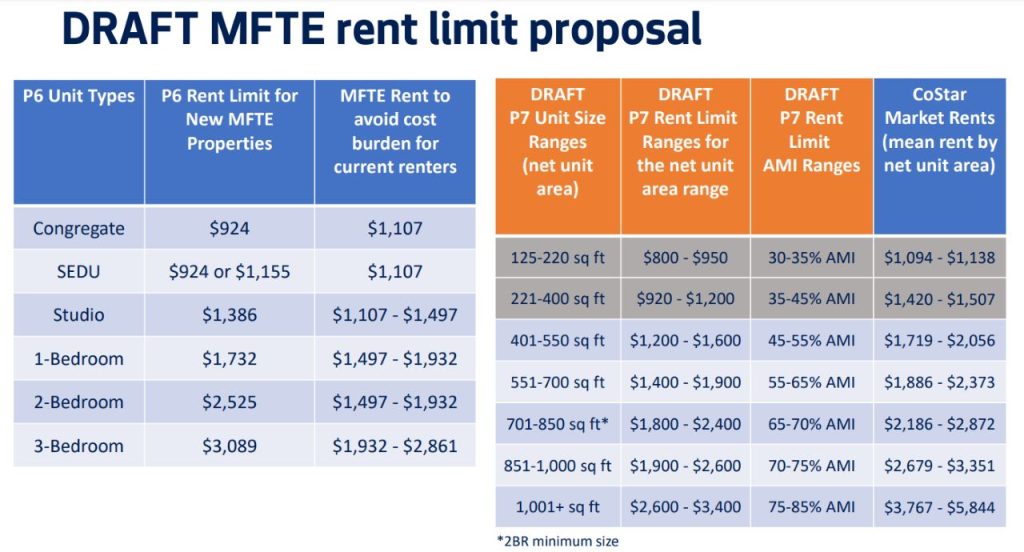

The proposed changes to P7 include stricter AMI limits to qualify. Comparing the existing AMI limits to the proposal is difficult because OH has shifted from categories such as studio, one-bedroom and two-bedroom apartments to a square footage calculation. All units between 125 square feet and 700 square feet (generally, the range for studio and one-bedroom apartments) must be offered (on a graduated scale) to those earning from as low as 30% AMI to 65% AMI. Units above 700 square feet (according Seattle’s building code, the minimum square footage for two-bedroom units) qualify on a graduated scale in a range between 65% and 85% AMI.

Effectively, what these changes mean is that in order to qualify for the tax exemption, units in the income target range of the original program goals (between 65% and 85%) must now be two-bedroom units.

Accordion to NAIOP’s analysis, the proposed changes to P7 would mean mean that income requirements for studio apartments would on average go from a current level of 60% AMI maximum to between 45% and 55%, one bedrooms from 70% AMI now to between 55% and 65% in P7, and two bedrooms from 85% AMI currently to between 75% and 85% in P7. NAIPO also contends that micro-housing units such as congregate residences and small efficiency dwelling units (SEDUs) will be impossible to finance with a new 30% to 45% AMI level.

In their letter, NAIOP observed, “Program 6 rents were barely workable. These even lower rents, which are at-par or lower than MHA AMI percentages, remove any incentive to participate in the program.”

Maritz said it’s shortsighted for OH to no longer encourage the building of more affordable studio apartments, which his firm specializes in building.

“They’re like: ‘We have a lot of studios already, so let’s incentivize people to do something other than studios,’” Maritz said. “They don’t understand: why are people building studios? People are building studios because that’s where the demand is.”

Barrientos said Seattle’s MFTE program has strayed from its original goal to incentivize the creation of housing for middle-income renters in walkable urban centers near abundant services, grocery stores, and transit.

“Do they still want to achieve those goals, or do they just really want to create a deeper layer of affordable housing?” Barrientos said, noting that at the proposed AMI levels, investors and developers will lose money. “If that’s the case, the private sector is unlikely to participate.”

In addition, OH has proposed significant increases in application fees for participation in the program. In P7, OH wants to increase the rate to a flat fee of $300 per unit, meaning a 100-unit apartment building would see its fee jump from $10,000 currently to $30,000, and a 250-unit building skyrocket from $10,000 to $75,000.

“Why on earth would it cost $60,000 per building to run this program?” Maritz wondered. “For them to literally process the one form they have to approve?”

Suresh Chanmugam, who’s on the steering committee of Tech 4 Housing, a group that advocates for housing density and affordability, said that while he understands that that staff expenses for Office of Housing are rising (it’s an expensive city to live in, he notes) the fees shift the burden to those who can least afford it.

“These changes the city is proposing do not do enough for families in the 60 to 120% range, and that in turn stifles the production of housing for developers who are participating in this program. The program fees are reasonable, but they should not be distributed to renters. It’s a tax on renters.”

In fact, MFTE tax exemptions are a relatively progressive revenue source that shifts some of the city’s property tax burden from renters in new buildings to commercial landlords, older apartment buildings, and single-family homeowners. This may offer a clue as to why the Harrell Administration has been lukewarm about MFTE; Mayor Harrell relied heavily on homeowners to run up its vote total in his landslide victory in 2021.

Martiz noted that, for instance, when a school levy is passed the assessor excludes properties in the MFTE program, and then spreads the cost – say, $100 million – among other property owners. “You’re shifting the tax burden from the residents of this new apartment building, who largely are middle class households,” he said, “to ratepayers on every other property in the city and the county, which is mostly single family homes and office buildings.”

Blanton believes the Office of Housing is trying to turn MFTE into a solution to too many affordable housing problems.

“We’re building a Swiss army knife here,” Blanton said. “Originally, it was a pocket knife. Then they wanted to have a corkscrew, and then pretty soon they wanted to have a spoon and a fork. And then it didn’t fit in your pocket anymore.”

While Chanmugam supports MFTE, he believes social housing, such as Seattle’s Proposition 1A which will be on the ballot in February and funds affordable housing through an employer tax on those who make in excess of $1 million per year, is a more effective, lasting solution. (Seattle Prop 1A is endorsed by The Urbanist Elections Committee)

“It’s very simple. It’s a single, publicly owned entity that builds and operates housing and charges people what they can afford to pay – it charges families up to 30% of their income.”

Barrientos is disappointed to see the MFTE program become more complicated and burdensome for developers and renters. “It makes me sad,” she said. “It’s not going to really hurt me as a developer, if we build at a pure market-rate. But it will hurt me a lot ideologically, in my values. It makes me sad that we won’t be able to provide that necessary housing in the urban center, which is primarily where I build.”

NAIOP, in its letter, calls on the Office of Housing to overhaul its proposal for the next version of MFTE, including returning AMI requirement levels to the 65 to 85% level to make projects economically viable, and keeping program fees at a rate that “reflects actual administrative costs.”

The letter concludes with a dire prediction for the MFTE program:

“The combination of dramatically increased fees, reduced AMI thresholds, exclusion of micro-housing, and burdensome operational requirements will make participation in MFTE financially unfeasible for most projects. This will result in fewer below-market units being built precisely when Seattle needs them most.”

Andrew Engelson

Andrew Engelson is an award-winning freelance journalist and editor with over 20 years of experience. Most recently serving as News Director/Deputy Assistant at the South Seattle Emerald, Andrew was also the founder and editor of Cascadia Magazine. His journalism, essays, and writing have appeared in the South Seattle Emerald, The Stranger, Crosscut, Real Change, Seattle Weekly, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Seattle Times, Washington Trails, and many other publications. He’s passionate about narrative journalism on a range of topics, including the environment, climate change, social justice, arts, culture, and science. He’s the winner of several first place awards from the Western Washington Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists.