A bill introduced by Seattle Council President Sara Nelson this week is set to reignite a debate over allowing housing on Seattle’s industrial lands and the future of the SoDo neighborhood. The industrial zone in question is immediately west and south of T-Mobile and Lumen stadiums, abutting the Port of Seattle. That debate had been seemingly put to rest with the adoption of a citywide maritime and industrial strategy in 2023 that didn’t add housing in industrial SoDo, following years of debate over the long-term future of Seattle’s industrial areas. This bill is likely going to divide advocates into familiar old camps during a critical year of much bigger citywide housing discussions.

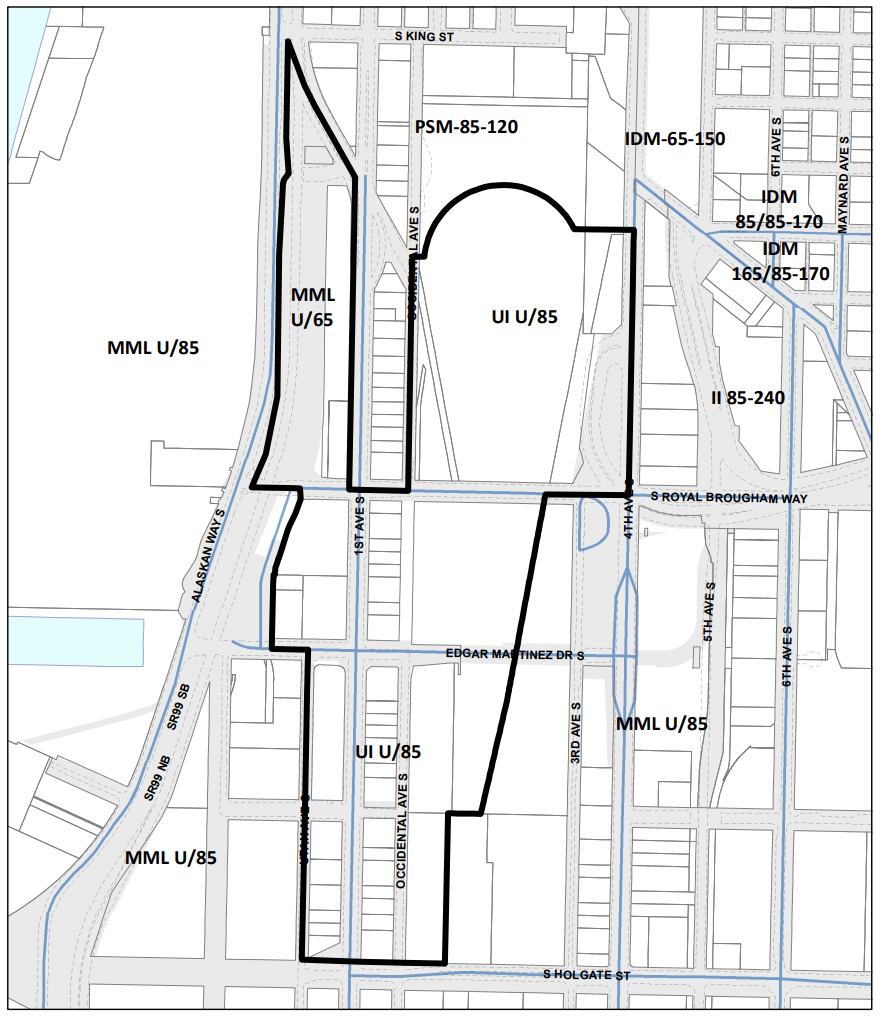

The idea of allowing residential uses around the south downtown stadiums, creating a “Maker’s District” with capacity for around 1,000 new homes, was considered by the City in its original analysis of the environmental impact of changes to its industrial zones in 2022. But including zoning changes needed to permit residential uses within the “stadium transition overlay district,” centered around First Avenue S and Occidental Avenue S, was poised to disrupt the coalition of groups supporting the broader package.

Strongly opposed to the idea is the Port of Seattle, concerned about direct impacts of more development close to its container terminals, but also about encroachment of residential development onto industrial lands more broadly.

While the zoning change didn’t move forward then, the constituency in favor of it — advocates for the sport stadiums themselves, South Downtown neighborhood groups, and the building trades — haven’t given up on the idea, and seem to have found in Sara Nelson their champion, as the citywide councilmember heads toward a re-election fight.

“There’s an exciting opportunity to create a mixed-use district around the public stadiums, T-Mobile Park and Lumen Field, that prioritizes the development of light industrial “Makers’ Spaces” (think breweries and artisans), one that eases the transition between neighborhoods like Pioneer Square and the Chinatown-International District and the industrial areas to the south,” read a letter sent Monday signed by groups with ties to the Seattle Mariners and the Seattle Seahawks, labor unions including SEIU and IBEW, and housing providers including Plymouth Housing and the Chief Seattle Club. And while Nelson only announced that she was introducing this bill this week, a draft of that letter had been circulating for at least a month, according to meeting materials from T-Mobile Park’s public stadium district.

Under city code, 50% of residential units built in Urban Industrial zones — which includes this stadium overlay — have to be maintained as affordable for households making a range of incomes from 60% to 90% of the city’s area median income (AMI) for a minimum of 75 years, depending on the number of bedrooms in each unit. And units are required to have additonal soundproofing and air filtration systems to deal with added noise and pollution of industrial areas.

But unlike in other Urban Industrial (UI) zones, under Nelson’s bill, housing within the stadium transition overlay won’t have to be at least 200 feet from a major truck street, which includes Alaskan Way S, First Avenue S, and Fourth Avenue S. Those streets are some of the most dangerous roadways in the city, and business and freight advocates have fought against redesigning them when the City has proposed doing so in the past.

The timing of the bill’s introduction now is notable, given the fact that the council’s Land Use Committee currently has no chair, after District 2 Councilmember Tammy Morales resigned earlier this month, and the council has just started to ramp up work on reviewing Mayor Bruce Harrell’s final growth strategy and housing plan. Nelson’s own Governance, Accountability, and Economic Development Committee is set to review the bill, giving her full control over her own bill’s trajectory, with Councilmembers Strauss and Rinck — the council’s left flank — left out of initial deliberations since they’re not on Nelson’s committee.

As Nelson brought up the bill in the last five minutes of Monday’s Council Briefing, D6 Councilmember Dan Strauss expressed surprise that this was being introduced and directed to Nelson’s own committee. Strauss, as previous chair of the Land Use Committee, shepherded a lot of the work around the maritime strategy forward, and seemed stunned that this was being proposed without a broader discussion.

“Did I hear you say that we’re going to be taking up the industrial and maritime lands discussion in your committee? There is a lot of work left to do around the stadium district, including the Coast Guard [base],” Strauss said. “I’m quite troubled to hear that we’re taking a one-off approach when there was a real comprehensive plan set up last year and to be kind of caught off guard here on the dais like this, without a desire to have additional discussion.”

On Tuesday, Strauss made a motion to instead send the bill to the Select Committee on the Comprehensive Plan, chaired by D3 Councilmember Joy Hollingsworth. After a long discussion of the merits of keeping the bill in Nelson’s committee, the motion was shot down 5-3, with Councilmembers Kettle and Rinck joining Strauss. During public comment, members of the Western States Regional Council of Carpenters specifically asked for the bill to say in Nelson’s committee, a highly unusual move.

Nelson framed her bill Tuesday as being focused on economic development, intended to create more spaces that will allow small industrial-oriented businesses in the city. Nothing prevents those spaces being built now — commercial uses are allowed in the stadium overlay — but Nelson argued that they’ll only come to fruition if builders are allowed to construct housing above that ground-floor retail.

“What is motivating me is the fact that small light industrial businesses need more space in Seattle,” Nelson said. “Two to three makers businesses are leaving Seattle every month or so, simply because commercial spaces are very expensive, and there are some use restrictions for certain businesses. And when we talk about makers businesses, I’m talking about anything from a coffee roaster to a robot manufacturer, places where things are made and sold, and those spaces are hard to find. […] The construction of those businesses is really only feasible if there is something on top, because nobody is going to go out and build a small affordable commercial space for that kind of use”

Opposition from the Port of Seattle doesn’t seem to have let up since 2023.

“Weakening local zoning protections could not come at a worse time for maritime industrial businesses,” Port of Seattle CEO Steve Metruck wrote in a letter to the Seattle Council late last week. “Surrendering maritime industrial zoned land in favor of non-compatible uses like housing invokes a zero-sum game of displacing permanent job centers without creating new ones. Infringing non-compatible uses into maritime industrial lands pushes industry to sprawl outward, making our region more congested, less sustainable, and less globally competitive.”

SoDo is a liquefaction zone constructed on fill over former tideflats and is close to state highways and Port facilities, but not particularly close to amenities like grocery stores and parks. The issue of creating more housing in such a location will likely be a contentious one within Seattle’s housing advocacy world.

Nelson’s move may serve to draw focus away from the larger Comprehensive Plan discussion, a debate about the city’s long-term trajectory on housing. Whether this discussion does ultimately distract from and hinder the push to rezone Seattle’s amenity-rich neighborhoods — places like Montlake, Madrona, and Green Lake — to accommodate more housing remains to be seen.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.