With the baton passing from Governor Jay Inslee to Bob Ferguson, emphasis has shifted to austerity, but some lawmakers aim to raise new revenue to avoid deep cuts.

With the 2025 Washington State legislative session beginning this week, Democrats have a bevy of policy priorities they are hoping to push through during the 105-day legislative session. But a budget deficit that could be as large as $15 billion over the course of four years might block some of their plans.

In the November election, Democrats increased their comfortable majority in both houses, and Democrat Bob Ferguson handily defeated his opponent to retain the Washington State governor seat. The Democrats also swept to victory with three of the four Republican-backed voter initiatives on the ballot being rejected by voters by wide margins. Voters came out in defense of the state’s new capital gains tax, the Climate Commitment Act, and its long-term care program.

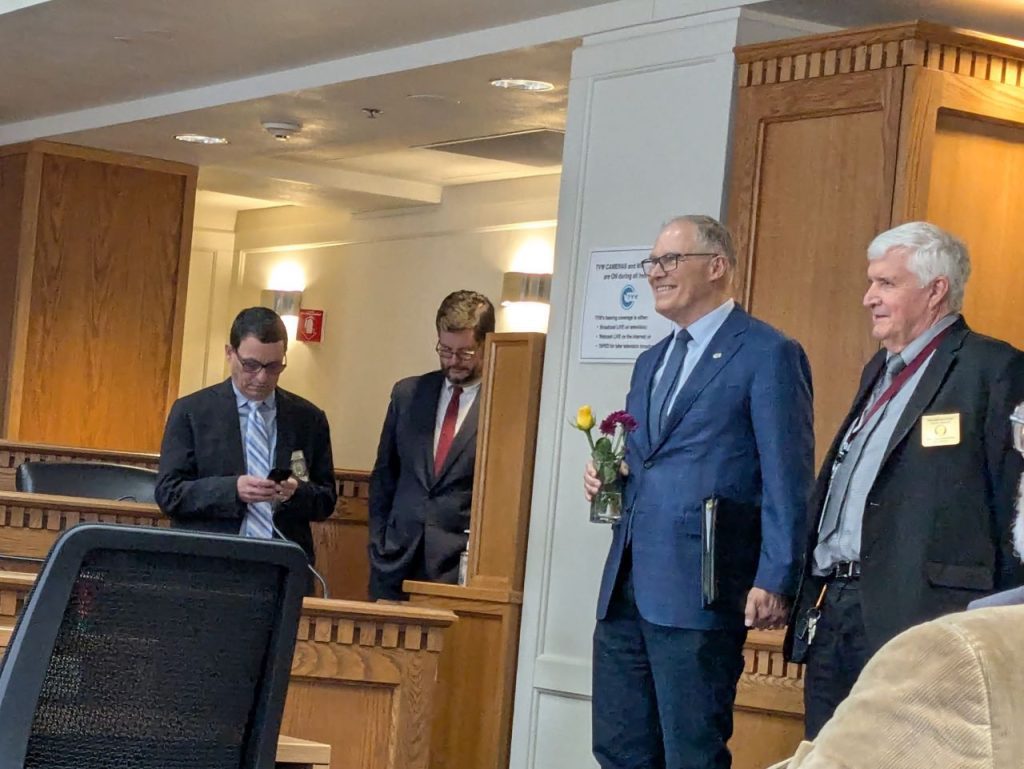

At a press conference last week, outgoing Governor Jay Inslee declared victory and suggested his policy agenda had been vindicated.

“You could not have had a more clear referendum on the direction of the state of Washington than we had last November,” Inslee said.

In contrast to Inslee’s message of hope, Ferguson chose to focus on the tough budget choices ahead, saying not everyone “fully appreciate[s] the scope of the budget challenge we have.” Ferguson poured cold water on hopes for new revenue, saying he has “deep skepticism” for the wealth tax Inslee backed to plug the budget hole. Washington’s new governor prefers cutting programs instead.

In his final “State of the State” address Tuesday, Inslee criticized Ferguson’s preferred approach. Inslee noted he proposed $2 billion in cuts in his December budget proposal, but pruning significantly deeper than that would jeopardize key programs and risk going back to “dark days” of the Great Recession.

“We have a strong economy; so, why would we consider cuts to programs like housing or mental and behavioral health services at a time like this, not when we’re finally seeing progress, not when the number of people needing these services is increasing, not when these programs are saving lives and making our communities safer and healthier,” Inslee said. “Washington voters just sent a strong message that they want to continue the path we’re building.”

Inslee urged policymakers to focus on the human impacts of budget decisions and portrayed a cut-heavy approach as inflicting pain on Washingtonians.

“Abstract, numerical cuts actually mean concrete, personal pain, like the pain of a kid who has to drop out of college because they can’t afford a tuition hike, like the pain of the mother who’s told there’s no room at the hospital for a child in the midst of a schizophrenic episode,” Inslee said.

A large budget deficit

In order to capitalize on their wins, Democrats will have to grapple with this large budget deficit.

In December, state officials reported a $11 billion deficit for the next two bienniums (July 2025 to June 2029) to the House Appropriations Committee. This number could grow to $15 billion once new labor contracts are included. And this doesn’t take into consideration a gap of at least $6.5 billion in the transportation budget through 2031.

While Washington’s economy is doing well overall, with Wallethub finding Washington has the best state economy in the country, the state is bringing in less revenue than originally anticipated, because consumer spending is down (lowering sales tax revenues), home sales are down, and the new capital gains tax brought in almost 45% less revenue in its second year.

At the same time, demand for publicly funded programs in the state has increased. The impacts of increased inflation from 2021-2023 mean programs, materials, and labor have become more expensive. And some programs, such as the Fair Start for Kids Act that aims to make child care and early childhood learning more accessible, are scheduled to expand.

Democrats are saying they will try to bridge the gap with a combination of cuts, slowing the growth of certain programs, and potentially adding new revenue.

“You don’t fill that kind of a hole with just one of those three things,” said Representative Timm Ormsby (D-3rd, Spokane), the Chair of the Appropriations committee.

“My first task is working through that exercise of what is possible and palatable for our members, and the public honestly, in terms of where we can make reductions and slow things down in the current budget,” said Senator June Robinson (D-38th, Everett), the Chair of the Ways & Means committee.

“I think we have a spending problem. We don’t have a revenue problem,” said Representative Travis Couture (35th Legislative District), the Republican Leader in the Appropriations committee.

His remarks provided an eerie echo to what many Seattle councilmembers and business leaders said last year in reference to Seattle’s budget deficit.

New taxes

In order to avoid an austerity budget, Inslee has proposed a wealth tax to help address the deficit. In his version, the state would levy a 1% tax on wealth over $100 million, which would impact around 3,400 Washingtonians and bring in an estimated $10.3 billion over the next four years. He also proposed increased B&O taxes on businesses that would bring in an estimated $2.6 billion over four years.

These two tax proposals would almost entirely address the anticipated deficit.

Other taxes on the table include a tax on big business similar to Seattle’s JumpStart tax, an increase of the capital gains tax to 9.9%, an 11% tax on guns, ammunition, and gun parts, and a new tax on “mansions,” houses that sell for over $3.025 million.

Another policy possibility is raising the cap on how much local governments can raise property taxes per year, which is currently limited to 1%, regardless of inflation. Municipalities such as Seattle and King County have been struggling since the inflation spike in 2021, as their revenues have not kept up with their expenses, a problem that continues even now that inflation has decreased to more manageable levels.

“I think it’s important for us to help our local partners,” Ormsby said. “Local governments could use more tools for generating rent.”

Republicans are adamantly opposed to introducing new taxes.

Democrat leaders have thus far refused to say if there are some tax proposals they prefer over others, instead emphasizing the need to weigh all the options and choose based on which tax(es) would work the best at generating much-needed revenue. They do, however, seem determined to consider progressive taxes that will address Washington’s upside-down tax code, ranked as the second most regressive in the nation after Florida. (It was the first most regressive until the recent passage of the capital gains tax.)

The legislature won’t start seriously discussing new revenue options until after a revenue forecast in mid-March, allowing them about a month and a half to formulate and pass a final budget proposal.

Ferguson pushes back on new revenue, backs budget cuts

Ferguson made headlines last week when he announced his own plan for Washington’s budget. He’s proposing a 6% budget cut across state agencies, excluding K-12 education and public safety (which constitute a sizable portion of the total operating budget). The 6% figure represents the average of the anticipated cuts, with some departments planned to take more cuts and some less. These cuts are estimated to save $4 billion over four years.

“You know, when you’re facing a budget shortfall, it’s no different than a family budget,” Ferguson said. “You’ve got to make your priorities. You’ve got to decide what’s most important. You’ve got to cut things you can cut. And that’s what we’ll be doing as a state.”

Ferguson has also proposed saving $300 million by resolving disputes in the tobacco master settlement and cutting $75 million from regulatory and civil law enforcement agencies, including $35 million from his former home, the Attorney General’s office, for affirmative litigation.

While Ferguson may be skeptical of a new wealth tax, he might not be opposed to new revenue sources on the whole, especially given the need to fund his own priorities. He did mention his past support for the capital gains tax in his role as state Attorney General — granted he’s obligated to defend state law in that role.

And when discussing new revenue proposals, Pedersen hinted at a larger conversation already in progress. “The incoming governor has an interesting idea about expanding the B&O tax on large, large corporations that have operations in Washington, similar to what we did with big banks a few years ago,” Pedersen said.

Meanwhile in his final official speech as governor, Inslee continued to put pressure on lawmakers to put everyday Washingtonians ahead of moneyed interests with high-powered lobbyists — folks who are largely pushing back against new taxes and fees to fund social programs.

“There’s one thing I know. There are influential people and organizations that have your phone numbers who are going to work those contacts hard all this session, whether the influential voices feed you over lunch or corner you out in those halls,” Inslee said. “Before you take that vote, I hope that you will think about the voiceless, the Washingtonians who don’t have your cell phone numbers, and remember why you’re here. We have to protect what they value the most, too, especially when it comes to our youth and our families. We have to go forward in our investments in young people and education.”

Legislative priorities

The Democrat and Republican caucuses have priorities for this legislative session that may sound similar on the surface.

“We’re looking at all the options possible to make sure we get a balanced budget but make sure that we keep on serving people,” House Speaker Laurie Jinkins (D-27th, Tacoma) said.

Jinkins went on to list the affordability of housing, child care, and health care and a focus on working families and children as priorities. She also referenced the importance of Medicaid.

“We are not going to stop doing Medicaid,” Jinkins said. “In fact, we are probably going to end up fighting the federal administration over things that they might want to do to the Medicaid program to restrict people’s access to health care.”

Senate Majority Leader Jamie Pedersen (D-43rd, Seattle) emphasized the importance of funding public education. Seattle Public Schools, like other school districts, has contemplated sweeping school closures in hopes of addressing budget deficits in some way.

“I think among our caucus, there is no other issue that is as important as doing our duty to public schools,” Pedersen said.

Pedersen said housing affordability and stability was the House Democrats’ second priority, including policies for rent stabilization and producing more affordable housing units.

Pedersen’s third stated priority was behavioral health.

“We see the effects of underinvestment in both mental health and drug treatment on the streets all around and in the lack of perception of public safety that is distressing for people across the state,” Pedersen said.

Across party lines, House Minority Leader Drew Stokesbary (R-31st, Auburn), also called out the state’s affordability crisis, including the prices of groceries and gas as well as housing. Stokesbary also referenced what he called the state’s public safety crisis.

“We have the fewest police officers per capita of any state in the country,” Stokesbary said. “And pick virtually any category of crime, violent crime, homicide, property crime, vehicle theft. Washington is probably one of the top five states in the country for each of those categories.”

While Washington does rank high in terms of property crime, it is ranked #28 by murder rate in the country and in a similar position for all violent crime.

Stokesbary would like to work to both hire more police officers and turn policing “into a profession that people can be proud of.”

The last priority Stokesbary mentioned was public education, saying he wanted to not only adequately fund the state’s schools but also hold them accountable for results.

Meanwhile, Governor Ferguson highlighted his priorities through specific budget proposals, while still emphasizing a cut-first approach overall. His new initiatives include:

- $100 million per biennium grant program to hire new law enforcement officers;

- $600 million in the state’s capital budget in additional funding more affordable housing;

- $20 million in the transportation budget to increase ferry service and aid in recruitment and retention of ferry workers;

- $480 million for universal school lunches; and

- $100 million to expand childcare eligibility for those working at small businesses.

How Ferguson will pay for these proposals remains unclear. But new revenue is likely to be part of the answer as the needs of Washingtonians do not appear to be diminishing.

“When we see our housing crisis, our K-12 funding crisis, our behavioral health work challenges that we have, so much of that stems from the cuts that we did during the Great Recession that we have not been able to recover from,” Jinkins said. “So we will have to do those hard looks at the budget and be values-based as we do that. But in the end, it is very hard for me to imagine that we won’t end up needing to look at some sort of revenue source or sources, once we are finished with that.”

Amy Sundberg is the publisher of Notes from the Emerald City, a weekly newsletter on Seattle politics and policy with a particular focus on public safety, police accountability, and the criminal legal system. She also writes science fiction, fantasy, and horror novels. She is particularly fond of Seattle’s parks, where she can often be found walking her little dog.