The majority of the funds for approximately 51 new positions are set to come from Seattle’s dedicated transit ballot measure.

In the wake of passage of the Seattle Transportation Levy last November, the City is preparing a hiring spree of new staff to handle transportation projects ranging from bridge maintenance to sidewalk construction. Separate from that new levy-funded work is another hiring spree of approximately 51 new employees that will be brought on to engage in planning work for Sound Transit light rail projects within the city.

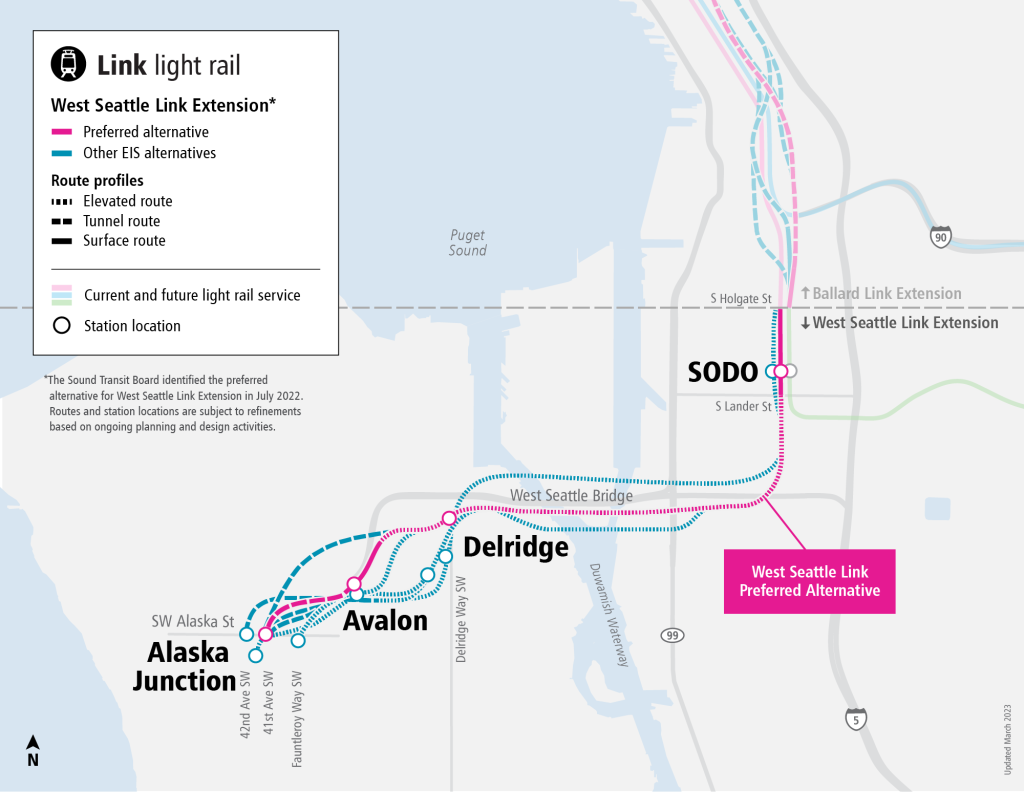

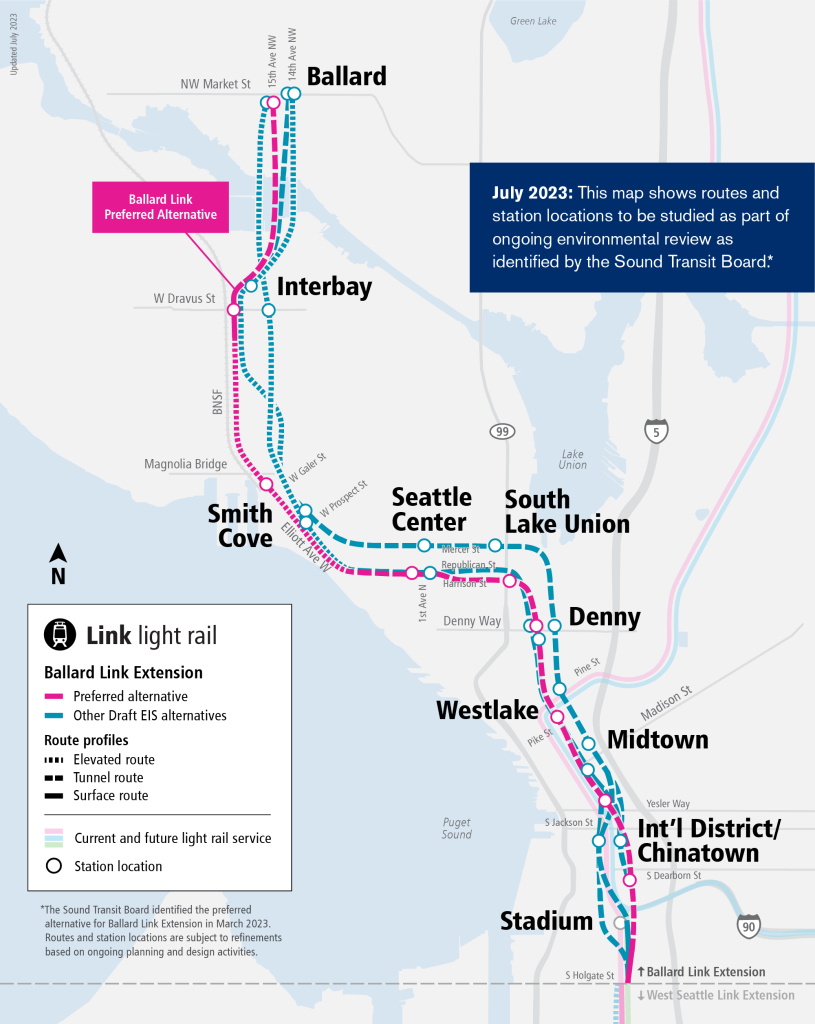

More than eight years after the 2016 Sound Transit 3 (ST3) ballot measure was approved by voters, Sound Transit is still a long way from starting construction on Seattle’s two major ST3 rail projects, West Seattle Link and Ballard Link. As the two projects advance further in design, the City of Seattle will need to review hundreds of permits, along with myriad design elements requiring city coordination.

In a brand new move, most of the funding for this planning work is set to come out of the 2020 Seattle Transit Measure (STM), a revenue source that was approved by voters to directly fund King County Metro bus service, upgrades to transit facilities, and transit passes for in-need Seattleites.

To unlock this funding, Mayor Bruce Harrell last fall proposed a change to what the STM can legally fund, expanding the allowed spending categories to cover Sound Transit work. While the Seattle City Council was debating a Delridge Way SW median and the future of the South Lake Union streetcar, this piece of legislation slipped by under the radar, expanding the scope of the 2020 transit ballot measure beyond what voters initially signed off on.

Unanimously approved by Council and signed by Mayor Harrell in late November, Council Bill 120887 allows the 0.15% sales tax on goods purchased within the city to now fund “staffing resources to support and complete The City of Seattle’s agreements and requirements necessary for implementation of the Sound Transit 3 program, including but not limited to dedicated and part-time staff to support project planning, permitting, and delivery of Sound Transit projects in Seattle.”

If that weren’t enough, Council Bill 120887 also allows the city to use the STM funding for contributions needed to pay for add-ons that come with its preferred light rail alignments, including a tunnel under West Seattle Junction and a tunnel under the Lake Washington Ship Canal to get to Ballard. That change could open the door to diverting a significant amount of transit service funding toward Sound Transit construction, even though the annual amount collected by the STM — around $50 million — pales in comparison to the costs associated with those projects. For now, the Harrell Administration is only proposing to use STM funding for planning staff.

While completing the permitting process for projects as large and complex as these two lines is undoubtedly a significant lift, it’s unlikely that voters had ST3 planning in mind when they voted to approve the 2020 transit ballot measure, which was set to be 33% smaller under the original renewal plan proposed by the Durkan Administration until it was revised by the City Council. With Metro facing a potentially significant financial crisis within the next few years as its fund reserves start to become depleted, Seattle will likely need all of the transit funding it can get its hands on in the coming years, but the adopted budget siphons nearly $9 million in STM funding away for new staff.

Overall, the adopted budget lays out $12 million in spending over the next two years on the approximately 51 additional positions, which will be added across various departments including the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT), the Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD), and the Office of Sustainability and the Environment (OSE). Apart from the close to $9 million of that coming from STM, the remainder is earmarked to come from the JumpStart payroll tax, under the auspices of the original 2020 JumpStart spending category of Green New Deal spending. Last fall, the Seattle City Council authorized ditching the original JumpStart spending plan (mostly dedicated to affordable housing) to fund a wide variety of other priorities.

This planned expenditure is set to more than double the number of Seattle city employees working on ST3. “Currently, 28 staff across multiple departments dedicate all or part of their time to the ST3 program,” the 2025-2026 budget book states. “This reserve would fund approximately 51 additional staff in multiple departments to support on schedule delivery of ST3 projects while ensuring compliance with relevant statutes and codes and upholding the 2018 Partnering Agreement [with Sound Transit].”

That 2018 partnering agreement, signed by then-Mayor Jenny Durkan, was intended to allow the city to work with Sound Transit to “meet the challenge of delivering projects as fast as possible,” and called for preferred alternatives for both Ballard and West Seattle Link to be selected within a year-and-a-half, with the Sound Transit board selecting a “project to be built” by 2022. Those timelines have not been met — West Seattle Link reached that milestone last year, two years late, while Ballard isn’t set to get there until 2026, in large part because of the addition or exploration of additional station alternatives supported by Mayor Harrell and King County Executive Dow Constantine.

It’s unclear where exactly things would sit if these planning agreements hadn’t been reached, but it’s hard to find any evidence of actual acceleration, despite pledges from the last two mayors to speed up ST3 work. Ballard Link has slipped from its original target of a 2035 opening to 2039, with even that tenuous due to projected budget overruns across the ST3 portfolio.

Regardless of the merits of the spending, the formal change to the Seattle Transit Measure sets a strong precedent for continued use of those funds beyond its formerly narrow scope.

Seattle has been directly funding Metro bus service to provide additional transit options for the city’s residents since 2014, when voters approved the precursor to the STM, the Seattle Transportation Benefit District. That six-year measure utilized close to 80% of its funding for Metro service, allowing Seattle to head into the pandemic at the end of 2019 with an additional 349,000 annual service hours on top of what Metro was already providing. But in 2024, the STM only funded an additional 140,000 hours, utilizing just over 50% of available funding. A major factor contributing to that wide gulf has been Metro’s struggle to hire enough operators to be able to expand service, with additional funding from Seattle sitting underutilized.

However, now Metro is making significant headways on hiring, and future expansion of service will depend heavily on how much funding is available to the agency.

Changes to the scope of the STM aren’t without precedent. In 2023, the Seattle Council approved a change to the STM allowing more funding to be used to support physical transit improvements, which was allowed under the original measure but only at a lower level. But with the allocation of funding for ST3 planning work, the STM seems to have fully transitioned to becoming Seattle’s all-purpose piggy bank, even as Metro has had to cut bus service on several highly-used bus routes within the city, including trips on the Route 10, 12, and 49. Last fall’s service change even left a swath of the city around Green Lake previously served by a bus route without one, after the deletion of the Route 20.

The $12 million for ST3 planning is currently budgeted as a two-year expenditure only, which aligns with the timeline of the Seattle Transit Measure, set to expire on April 1, 2027. While some regional leaders are starting to explore what it would look like for a transit-funding measure to go countywide, it’s not at all clear what the City of Seattle’s vision for the next iteration of its citywide transit measure would be, beyond being a handy source of revenue for transit-related projects. But the city will likely need some type of funding source for ST3 planning beyond 2026, with Ballard Link not expected to reach final design until four years after that.

Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) spokesperson Ethan Bergerson told The Urbanist that the department is still working on a specific plan on how the STM funding will be used for ST3 planning, but that the positions will be divided into three buckets: station area planning and access projects, technical support for Sound Transit, and ultimately permit review when the agency starts to submit the more than 200 applications that are expected as part of West Seattle and Ballard Link.

“SDOT is developing a resource plan that will detail how the new 2025-2026 budget authority will support these bodies of work,” Bergerson said. “The 2025-2026 budget authority was held in reserve knowing that we will return to Council in 2025 with a specific staffing request once the resource plan has been developed in concert and alignment with Sound Transit’s schedule and workplan.”

Bergerson painted the planned expenditures to hire this small army of staff as being necessary to deliver the ST3 projects as fast as possible. Final delivery of West Seattle Link has already slipped two years, from 2030 to 2032, and Ballard Link has slipped four years, from 2035 to 2039.

“The City has critical roles to support Sound Transit’s projects that, if fully resourced and realized, will facilitate project delivery, maximize public benefit, and minimize harm to existing communities,” Bergerson said. “In the next four years, as planning moves to final design, permitting, and construction, the City will oversee an enormous volume of work to support on time and on budget project delivery. By dedicating additional staffing resources to the City’s ST3 Program, we are working to prevent ST3 project schedules and overall delivery timelines from negative impacts.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.