Behind-the-scenes emails show a sustained push to water down a project intended to calm traffic on one of the city’s most scenic routes.

On the evening of December 12, a community room on the upper floor of Mt. Baker Rowing and Sailing Center was packed to capacity for a public meeting. The topic was Lake Washington Boulevard, the winding arterial street that sits on Seattle Parks and Recreation land throughout most of Southeast Seattle. Despite the fact that the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) has been adding speed cushions to slow traffic throughout the city without much controversy, changes to Lake Washington Boulevard have prompted a stronger reaction.

To many attendees, the purpose of the meeting was a little unclear. Weeks earlier, an initial series of speed cushions and other safety improvements had been installed along different segments of Lake Washington Boulevard, the first of two phases of work that were announced in late summer. With the second phase not set to go in until this upcoming spring, there was a sense that holding another meeting meant that the project’s completion was very much at risk, after so much outreach had already been done.

Ahead of the meeting, Seattle Neighborhood Greenways had created a letter-writing campaign to support the second phase of work, and although the city employees leading the meeting shied away from the topic of shelving the remaining improvements, that possibility hung in the air throughout the night.

Adding traffic calming to Lake Washington Boulevard shouldn’t be controversial, given the current conditions on the street. The relatively low volume of vehicle traffic means speeding by drivers is near-constant, with close to one in three drivers going at least 10 mph over the 25 mph posted limit, according to a 2023 speed survey. Without a significant traffic calming upgrade to the street, accessing the park space along the lake — including popular Mount Baker Beach and other popular gathering spots — would continue to be intimidating, and the roadway would almost certainly remain unwelcoming to most people on bikes trying to travel north-south. But the improvements stop well short of what many would like to see — a full rethinking of having a busy arterial along a parkway — Lake Washington Boulevard is actually Seattle Parks property.

At that December 12 meeting, many attendees praised the safety enhancements.

“This summer, there were four accidents where people were meaningfully injured, and I was the first responder: my wife and I are the first on the scene whenever that happens. And we get to call 911 and have 911, come out and respond to a serious accident,” one attendee said during the meeting’s open forum. “Since the speed humps have been installed, there has been one — someone hit someone’s dog, and the dog was just fine. So thank you to the speed humps for slowing things down and the pedestrian crosswalk for literally saving multiple injuries going forward.”

Others in attendance clearly saw the speed humps as a symbolic change, larger than just the issue of slowing down drivers through a park.

“These speed bumps are a disaster,” another attendee said. “Everything you guys are doing to the South End is a disaster, in my opinion, the road diet on Rainier Avenue, the bus lane on Rainier Avenue, all I’ve ever seen there is cars speeding through it. And you’re squeezing off the South End to the rest of the city.”

Despite the success of the popular “Keep Moving Street” along Lake Washington Boulevard in 2020 and 2021, in which the roadway was closed to through traffic between Mount Baker Beach and Seward Park for months at a time, the idea of changing how the street operates has mostly lost its momentum. The group Coexist Lake Washington, whose website states support for making improvements “without adversely affecting people who drive,” has advocated strongly against major changes to the street, and a specially-created taskforce that met in 2022 and 2023 and deadlocked on the issue.

While traffic calming was the compromise solution on paper between competing paths forward, communication behind-the-scenes shows a different story. Last spring, after Parks released its initial list of improvements, members of Coexist Lake Washington contacted the department to push back on multiple aspects of the design, which was positively received in a City survey. Emails obtained by The Urbanist in a public records request show a sustained push to get elements changed even before they were installed.

“Some of these [changes] are so poorly thought out that they may worsen safety – on a roadway that is currently one of the safest arterials in the city,” Theresa Huey, who represented Coexist Lake Washington on the now-disbanded task force, wrote in a May email. “That in turn would lead to calls to reduce driver access. As you know, there is already a vigorous campaign underway to change the road’s designation as an arterial and permanently close one lane on the boulevard.”

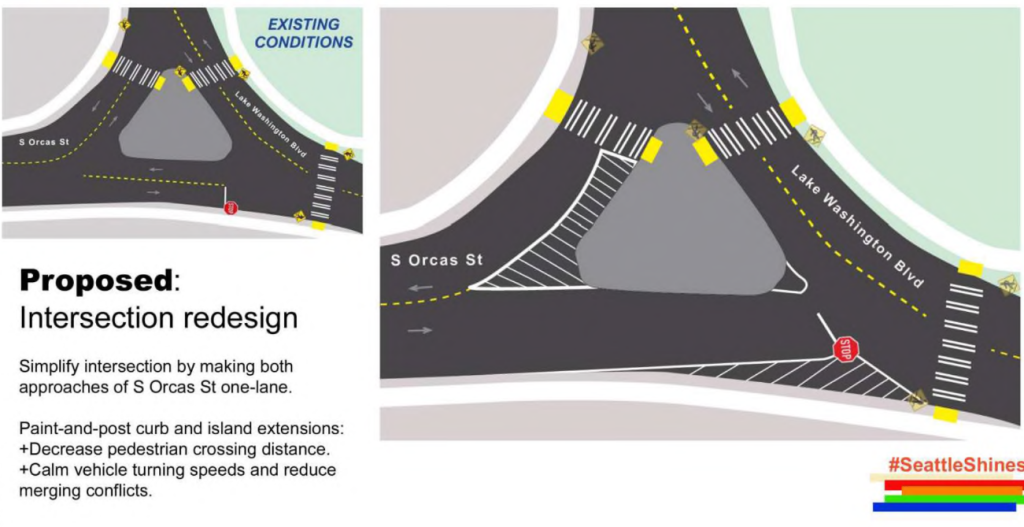

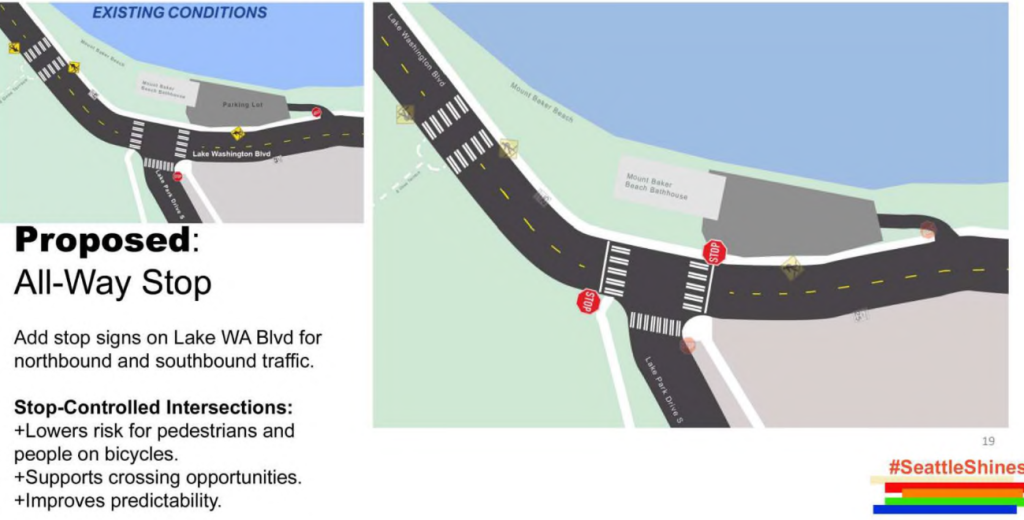

The group took issue with plans for an all-way stop at Lake Washington Boulevard and Lake Park Drive S, narrowing of intersections at 43rd Avenue S, 51st Avenue S, and S Genesee Way (a proven safety countermeasure), a new marked crosswalk at S Ferdinand Street, and a rechannelization of a tricky intersection near Seward Park, at S Orcas Street. “This proposal has no evident benefits and the funds would be better used adding raised crosswalks on Lake Washington Boulevard or pedestrian-activated crossing lights,” Huey wrote of the Orcas Street proposal, which would reduce conflicts by converting two legs of the three-way intersection to one-way.

In June, a follow-up email sent to SDOT Director Greg Spotts by another Coexist member, Tai Mattox, took direct aim at the all-way stop proposed at Lake Park Dr S, next to Mount Baker Beach.

“The stop sign seeks to solve a problem that doesn’t exist,” Mattox’s email stated. “The stop sign will create traffic congestion and increased pollution that will impact everyone on and around the boulevard: drivers, pedestrians, cyclists, park and beach goers, and local residents […] The stop sign will increase conflicts at the intersection – and further down the road as travelers become frustrated by backups and delays.”

The email also asked the City to cancel the planned upgrades at Orcas Street and the redesign of the 41st Avenue and 53rd Avenue intersections, and instead use the dollars earmarked for those projects on rapid rectangular flashing beacons (RRFBs) at Lake Park Drive S. RRFBs alert drivers to the presence of people trying to cross at marked crosswalks, but don’t force drivers to actually stop.

After Mattox’s email, a meeting was scheduled between Mayor Bruce Harrell’s office and Coexist Lake Washington, for July. In advance of that meeting, a memo created by Parks specifically outlined the reasons why RRFBs aren’t seen as an appropriate substitute for the all-way stop at that location, with a response to the idea that it will create congestion. “Vehicles will need to stop, so there will no longer be free flowing traffic through this intersection, but significant delays are not anticipated,” the memo noted.

Despite the fact that the all-way stop had been vetted by SDOT prior to its inclusion in the plans, after the meeting between Harrell’s office and Coexist Lake Washington, SDOT reversed its position and told Parks to drop it from the plans. The Urbanist noted the reversal in early September, but the emails now show that it was the Mayor’s office that forced the change.

“Since this meeting, we have received direction from SDOT to remove the all-way stop and replace with additional speed cushions and signage,” Seattle Parks’ Jordan Hoy, the planner in charge of the Lake Washington Boulevard improvements, wrote in an email to a colleague in late July. “I am still trying to understand this decision, as it is not consistent with community feedback or recommendations based on SDOT traffic engineering expertise. An all-way stop warrant data analysis was conducted and determined that this intersection would be a good candidate for this treatment.”

This isn’t the first time that Mayor Harrell’s office has directly overridden a department’s decision when it comes to Lake Washington Boulevard. Records from last year revealed how Adiam Emery, Executive General Manager in Harrell’s office, stepped in after the Parks department announced expanded hours for the popular Bicycle Weekends closure events along the street, and then quickly reversed itself. At the time, Emery cited an “extensive outreach effort” that resulted in the scaled-back schedule, despite consistent city surveys showing broad support for extended closures of the street to vehicles

With the sustained push to undermine city staff trying to make Lake Washington Boulevard safer exposed to sunlight, December’s community meeting makes much more sense. And while there were a fair number of residents who showed up to push back on completing phase two, there was also clear community support for continuing among the packed room. Ultimately, that may not be enough to stave off backsliding, but for now Parks says the improvements are still on track to be implemented.

One thing is for sure: even completing those upgrades won’t put to rest a debate about the best way to utilize Lake Washington Boulevard as a city asset for all of Seattle to enjoy.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.