SCIDpda is seeking to anchor communities of color in place in and around Seattle’s Chinatown-International District, with Beacon Pacific Village its latest example.

When I walk into the new Beacon Pacific Village apartment building, which sits across from the iconic art-deco Pac-Med tower, the first thing that catches my eye is a colorful mural. Every floor has its own unique artwork designed by a local or West Coast artist. The units themselves are airy and light-filled, with sleek counter-tops and sweeping views of the city stretching from Smith Tower to the Chinatown-International District (CID).

The roof boasts solar panels and the windows are triple-paned to block pollution in accordance with the Exemplary Building Challenge. Meanwhile, the ground floors are home to services for both kids (El Centro de la Raza’s bilingual education center) and older adults (International Community Health Services’ senior center).

Owned and operated by a long-running nonprofit, Seattle Chinatown International District Preservation and Development Authority (SCIDpda), Beacon Pacific Village is a model for livable, integrated affordable housing. Jamie Lee and Jared Jonson, who are SCIDpda’s co-executive directors, describe Beacon Pacific Village as an extension of SCIDpda’s mission to counter displacement.

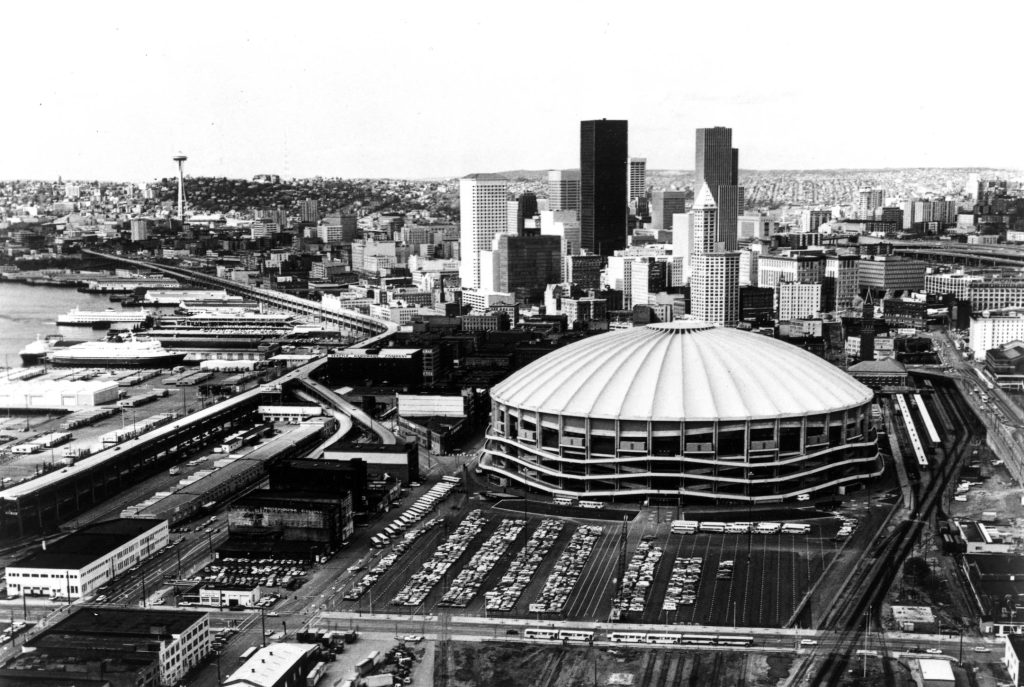

Seattle Kingdome protests launch SCIDpda

SCIDpda was founded in 1975 in response to the construction of the Kingdome, which sparked protests and opposition from neighbors in the CID.

“Our community was concerned about the Kingdome’s impacts to small businesses, overall economic development, and traffic. They wanted better access to affordable housing, jobs, and health care. Fundamentally, all those issues are still relevant 50 years later,” Jonson explained.

Today, SCIDpda operates nine buildings with around 600 units of affordable housing, plus a quarter million square feet of commercial, office, and retail space. Their next venture is The Landmark Project, a “community-owned space for affordable housing, commercial spaces, and a cultural center” in partnership with Friends of Little Sài Gòn. With land already procured at the corner of 10th Avenue S and Jackson Street, the project is slated to begin construction in late 2025.

Adding 160 homes affordable to households making less than 60% of area median income, Beacon Pacific Village is its second project located outside of the CID, albeit by only one block. SCIDpda’s myriad community initiatives range from a window protection program for small businesses affected by crime to grant assistance for property owners to renovate in compliance with historic preservation laws.

“We think about preservation in two ways. There’s a preservation of culture and place, and then there’s a preservation of physical buildings,” Lee said. “For a lot of people, preservation means that things stay the same, and that’s not how we think about it. How do we help the neighborhood stay as true and authentic to itself while also evolving into what works for today?”

Seizing opportunity on the Beacon Hill edge of CID

The story of Beacon Pacific Village is one of thoughtful, painstaking growth. The lot was originally owned by Amazon, but it was left in limbo when the company moved out of the Pac-Med tower and into its new digs in South Lake Union. Enter Frank Chopp, the state legislature’s tireless advocate of affordable housing. Chopp was Speaker of the House from 2002 to 2019, and finally retired last year, passing the 43rd Legislative District reins to Shaun Scott, who won election this past fall.

In 2017, Chopp reached out to Maiko Winkler-Chin, who was SCIDpda’s executive director at the time, to inquire about developing the site — Winkler-Chin now leads the Seattle Office of Housing. SCIDpda chose to partner with the CID-based Edge Developers, kicking off a seven-year process of wrangling more than a dozen different funders.

Like SCIDpda, Edge Developers has a classic CID origin story: all three partners are South Seattle natives who met while attending schools in the area and formed their company so they could make a difference in the community they grew up in. Today, decades later, Edge naturally gravitates towards affordable projects in the CID or South End. Although Edge is a small for-profit, it often partners with nonprofits led by people of color, explained Joel Ing, one of the company’s partners.

From the very beginning, Edge and SCIDpda were on the same page about prioritizing family-based housing. “Our goal is to preserve a place for immigrants and refugees, and we see housing as our strongest tool to do that,” Lee said.

But housing construction in Seattle is often skewed towards studios and one-bedrooms for a simple reason: it’s what funders want. Many funders seek to maximize the number of units, not the total number of people housed.

“The metric that a lot of funders use is: How many units does X dollars bring? So we’re trying to change that narrative,” Ing said.

Partnerships with El Centro de la Raza and International Community Health Services (ICHS) were also key to making Beacon Pacific Village appealing to families.

“We are honored and grateful to be a part of the new Beacon Pacific Village, and the vision of SCIDpda to co-locate housing with childcare and elderly care facilities to deliver support and services that will allow families to stay in the neighborhood where they have lived for generations,” ICHS CEO Kelli Nomura said.

This new Ron Chew Healthy Aging and Wellness Center will quadruple the number of older adults served by ICHS. Their services include fitness, social activities, primary care, medication management, and occupational and physical therapy. ICHS emphasizes culturally sensitive care, and offers services in over 70 languages.

“The program is designed to empower seniors to stay active, stay connected, and stay rooted in their homes and communities,” said Nomura.

The CID’s history of resilience and Seattle megaproject impacts

Since SCIDpda’s inception 50 years ago, the CID has weathered many challenges. But the neighborhood finds itself at a particularly tricky crossroads, with high-profile debates around crime, homelessness, and displacement. SCIDpda is no stranger to these issues: during the pandemic, SCIDpda’s staff witnessed a rise in behavioral health crises in their buildings, leading them to implement a resident services program.

The pandemic-triggered downturn in foot traffic in Downtown Seattle also hit CID businesses hard. CID business owners complained that major events like the 2023 Major League Baseball All-Star Game failed to bring patrons to their doors. Negative coverage in the news may also be discouraging people from making the trip in from other neighborhoods or suburbs.

“There’s good things happening that never get highlighted by the mainstream media,” Jonson said.

Infrastructure debates loom large in the CID, which was bisected by Interstate 5 in the 1950s. The state transportation department demolished an entire swath of Chinatown to make way for the freeway, which displaced around 40,000 Seattleites in all — despite a local freeway protest.

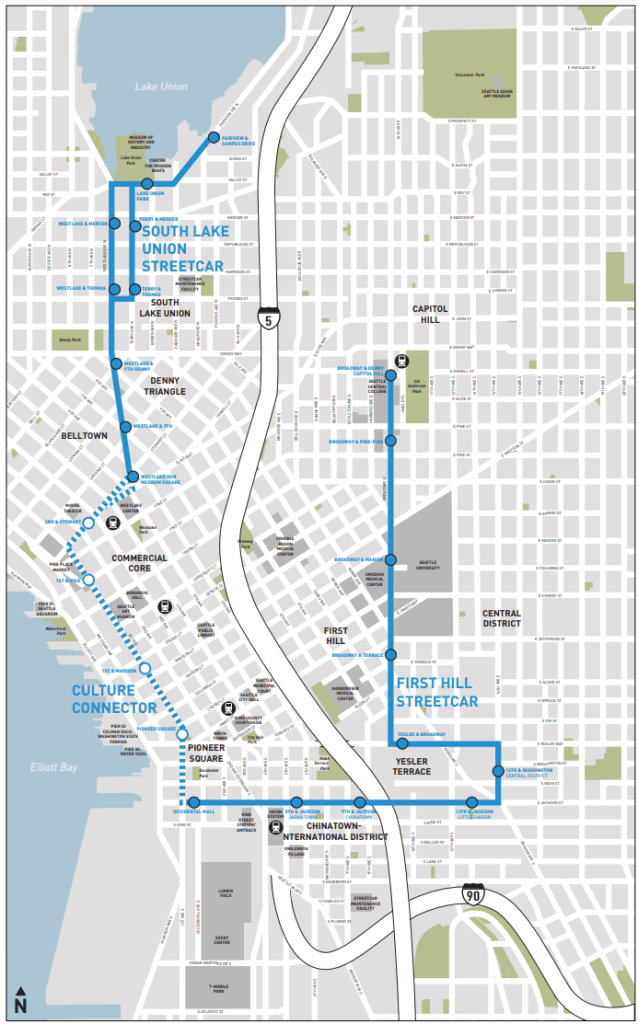

In the 2010’s, the CID weathered First Hill Streetcar construction on Jackson Street with the promise that the line would one day connect to downtown and Pike Place Market, bringing tourists and locals into the CID. Mayor Jenny Durkan shelved the Center City streetcar extension in 2018, however, and Mayor Bruce Harrell, despite renaming it the “Cultural Connector” to highlight its CID connection, has failed to marshal resources needed to resurrect the project.

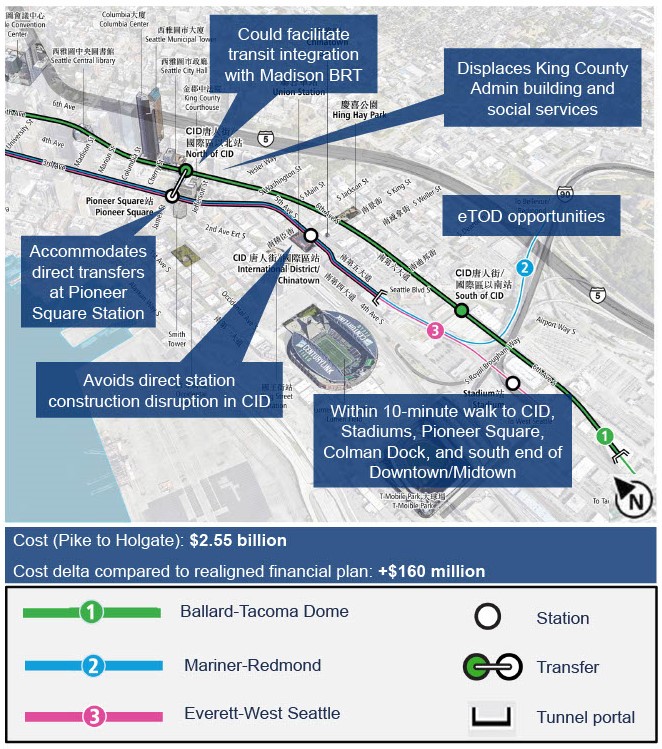

Today, one of the thorniest issues is the location of Sound Transit’s new light rail station coming with the Ballard Link extension. SCIDpda has maintained their preference for a 4th Avenue station, despite the release of a new report outlining major risks and buttressing the Sound Transit Board’s decision to back a new alternative skipping Chinatown.

SCIDpda is thinking long-term, Jonson explained: “We are willing to suffer through that period of construction, and are willing to step in and try to help mitigate that as much as possible, in order to get this 100-plus year benefit, which is essentially another station at the front door of our neighborhood.”

The organization feels confident that the neighborhood can survive construction impacts, just as it survived I-5 and the Kingdome.

“This community is here to stay,” Lee said. “We’re resilient.”

Alison Jean Smith

Alison Jean Smith is the Local Sightings Director at Northwest Film Forum, a member of the TeenTix Alumni Advisory Board, and a contributor to REDEFINE, an online magazine where she interviews both emerging and established filmmakers. She has also had her writing published in The Stranger, The South Seattle Emerald, and on the doubleXposure podcast website. Topics she’s covered range from wild horse training to debates over light rail. She is currently studying communication at the University of Washington.