With a state budget deficit looming, Olympia may consider a JumpStart-like corporate payroll tax

Progressive tax nerds, it’s time to grab your policy briefs and your pitchforks and head down to Olympia. This year’s legislative session is going to be a doozy.

Over the next four years, Washington state is facing an operating budget deficit estimated at $10-12 billion, or a few billion annually. The total current biennial budget is around $72 billion, so we’re talking about a 7% or so gap. That’s thanks to inflation, labor contract costs, growing demand for social services, and chronic underfunding of education, among other factors.

“When you look at what’s driving the gap, people are taking advantage of the programs we passed,” said Sen. Noel Frame, who serves as vice chair of the Finance Committee. “Caseloads are up because it turns out that when you pass essential services that people need and demand, people use them. Working Connections Child Care, Fair Starts for Kids — people are utilizing this stuff and it costs money.”

Rising costs are colliding with our state’s still-regressive tax system and declining inflation-adjusted revenue. The state transportation budget is in trouble, too. And don’t expect any help from the other Washington.

All this means that the Legislature’s newly expanded Democratic majorities have their work cut out for them. To prevent an all-austerity budget, they’re going to need to find new revenue. And they may have to overcome resistance from Governor-Elect Bob Ferguson, who so far has sounded a fiscally conservative note, focused on finding “savings” and “efficiencies.” New taxes can be a tough sell with the American public, too, a problem progressive tax advocates are wrestling with.

“We’re really trying to shift the way people have been so conditioned to think about taxes and taxation,” said Alexis Mansanarez, Communications Director at the Economic Opportunity Institute. “This is for the public good. This is about creating an economy that works for everyone, not just the wealthy few.”

Thanks to an email mishap by Sen. Frame just before the holidays, the Senate Democrats’ tax menu for the upcoming session is out in the news. But it wasn’t exactly a secret. Earlier in December, the Balance Our Tax Code Coalition (full disclosure, the Transit Riders Union is a member) had already held a couple of “Revenue Readiness” webinars for lawmakers and advocates. The recording and accompanying slideshow give a good rundown of the state’s budget problem, some progressive tax options that are likely to be considered this year, and advice on messaging.

State employer payroll tax proposal

There’s a lot of good stuff in there. But the tax idea that jumps out to me (never too early in the year for a good pun) is a tax on big business similar to Seattle’s wildly successful JumpStart tax. Like JumpStart, it would be a payroll-based tax focused on employers with a high-salaried workforce. But there’s a twist: It would be fashioned to effectively close a loophole in the federal tax code.

Most of us working stiffs pay 6.2% out of each and every paycheck to fund the Social Security system, and our employer matches that contribution. (Self-employed workers pay 12.4%.) But there’s a maximum taxable threshold, which for 2025 is $176,100. Any pay above that amount is (Social Security) tax free. To put the matter another way: If you’re lucky enough to make a million dollars a year, every year you and your boss stop paying into the Social Security system after just 64 days, in early March. Freeloaders!

Absent federal action to “scrap the cap,” this is a field ripe for the harvest by enterprising state and local governments. Washington state may be ready to step up. In the upcoming session, lawmakers may consider taxing employers at a rate of 6.2% on payroll in excess of the Social Security threshold. This would capture the employer portion of the missing Social Security tax; it would not tax the employee.

Applied only to companies with $8 million or more in Washington payroll, about 4,000 employers would pay about $3.8 billion a year by 2029. An alternate version covering all employers could generate $4.2 billion a year by 2029.

The Seattle question: preempt, credit, or stack?

I think this is an excellent idea. But it does raise some questions about how such a statewide payroll-based business tax would interact with Seattle’s JumpStart tax.

In the simplest scenario, it would layer right on top. My guess is that this would at least double what Seattle employers are already paying through JumpStart. (Seattle is roughly one tenth of the state by population, but has more than its share of high-paying jobs; JumpStart is projected to bring in somewhere north of $400 million annually in the coming years.) No doubt the tech giants, high-powered law firms, and other companies subject to these taxes can afford the increase, but they’ll whine and fight. So, legislators are likely to consider a different approach.

The state could, instead, give employers credit against their state tax bill based on the local tax they already pay. A full credit would mean the state foregoing a significant chunk of revenue. Lawmakers could opt instead for a partial credit, which could take any number of forms: a percentage of the JumpStart tax a business pays, for example, perhaps capped at a percentage of the state tax owed on Seattle-based payroll.

How a credit is structured won’t just impact revenue collection in the short term. It could also create incentives for local jurisdictions looking to adopt — or in Seattle’s case, expand — a JumpStart-like tax in the future. A full credit could spur, say, Bellevue or Redmond to pass a replica of the state tax, as that would simply shift revenue from state to city. If the point is to bolster the state budget, such erosion would be counterproductive. A partial credit, on the other hand, could offer an interesting compromise. It could encourage local action by somewhat blunting business opposition, while also resulting in greater combined state and local revenue flowing from wealthy corporations.

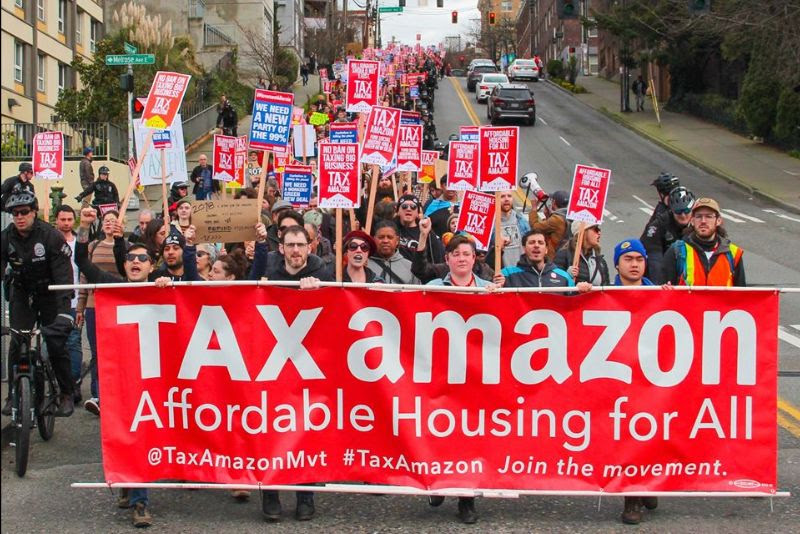

Business lobbyists will, no doubt, push for another approach. If they can’t prevent a state employer payroll tax from passing, they’ll at least want limits or an outright ban on local versions. We saw this back in the pre-JumpStart days of early 2020. Amazon and other corporations appeared poised to support House Bill 2907, which would have authorized a modest King County-wide employer payroll tax, on the condition that cities within the county be prohibited from passing similar taxes. At the time, “Tax Amazon” activists were gearing up to gather signatures for a Seattle citizen’s initiative.

This time around, perhaps they would allow JumpStart to be grandfathered in with a credit — after all, the Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce recently applauded the repurposing of JumpStart revenue to support what they consider basic city services, so they can’t very well try to kill it now. Whatever the demand, progressive lawmakers and advocates should draw a deep line in the sand and reject any form of preemption. We need more, not less, progressive local tax authority.

No decisions have been made, of course. “Everything is still to be discussed and negotiated,” said Sen. Frame. She expects that some legislators will strongly oppose any form of preemption, while “there might be others who say they wouldn’t vote for this if there wasn’t preemption.”

Taxing income and closing loopholes

Apart from squeamishness about offending our corporate overlords, there’s no reason for lawmakers to hesitate to pass this tax without any preemption “poison pill.” In fact, Democrats who bemoan Washington’s lack of a progressive income tax should understand this as the next best thing. The payroll tax base is similar to the income tax base, if less expansive; and like an income tax, an employer payroll tax is relatively easy to adjust in a fine-grained manner to determine who pays and at what rates.

This is in contrast to our state’s other major revenue sources, notably the incorrigibly regressive sales tax, which hits the poor much harder than the wealthy.

There is actually one thing lawmakers could do to make the sales tax less regressive, and if I could add one more option to the Senate Democrats’ tax menu, this would be it. Sales tax revenues are flagging in part because of the shift to a more service-based economy; as I discussed in a recent Urbanist column, most personal and professional services are exempt from the sales tax. Back in 2016, the Washington State Department of Revenue estimated that repealing this outdated exemption could generate an extra $2.4 billion in state revenue and $1.1 billion in local revenue in 2019. That’s real money and governments should be capturing it.

Anyway, I shouldn’t complain — between the employer payroll tax, a business and operations (B&O) tax surcharge on the largest corporations, a wealth tax, and several others, there will be plenty of good ideas at play in the upcoming session. As I wrote back in the pre-JumpStart days of 2019, I have a not-so-secret scheme to enlist the help of Amazon and its ilk in actually winning a progressive income tax one of these years. We just have to keep ratcheting up the big business taxes. Eventually they’ll realize that until they put their political muscle behind an income tax, they’re going to be the piggy banks.

JumpStart was a wonderful start, and Seattle voters will have a chance to add another layer this February when they vote on Prop 1A, an Urbanist-endorsed measure that funds social housing with an excess compensation tax. Here’s hoping the Legislature takes another big step.

One way or another, the scale of the budget shortfall demands action. The Legislature faces “a gigantic puzzle of what combination of cuts and what combination of revenue sources will make it all work,” said Sen. Frame. “People need to lean in, and if they don’t want to see pretty severe cuts, we need to really speak with one voice. This is a real moment and opportunity to solve this issue right now by making some significant improvements to the tax code.”

Katie Wilson is General Secretary of the Transit Riders Union, a Seattle-based organization advocating for improving transit quality and making access more equitable. In 2025, she launched a run for Seattle Mayor.