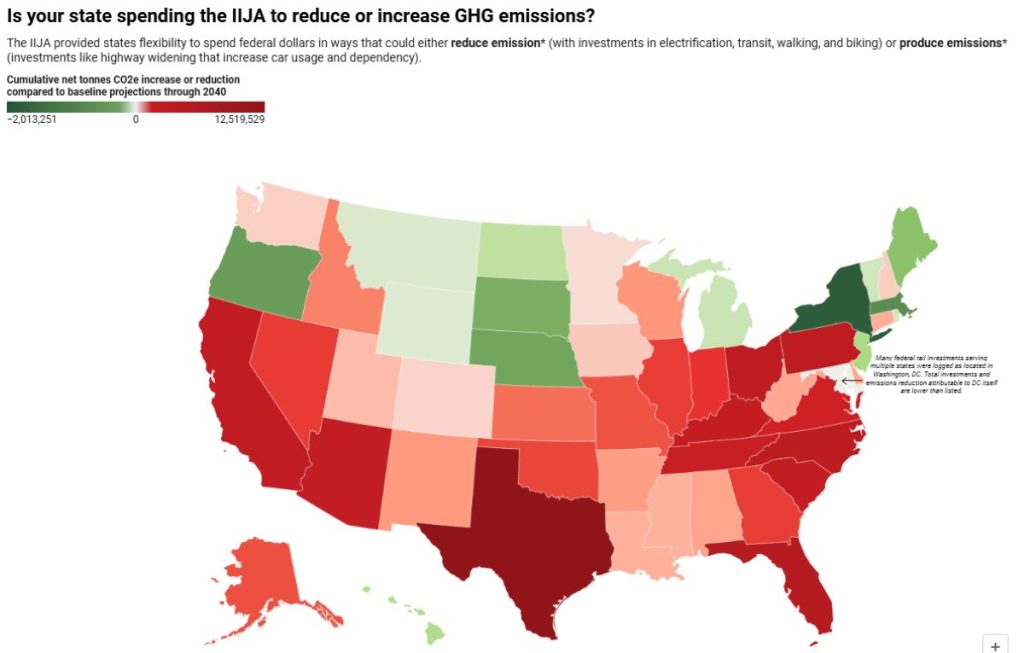

Most states continue to funnel money toward highway expansion, locking in climate pollution, despite new tools to fund green infrastructure.

A new report from Transportation from America has found that the supposed climate-friendly Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) has, to date, resulted in increased emissions. In addition, it could potentially even undo some of the emissions reductions achieved under other legislation taking action on climate, such as the Inflation Reduction Act.

The bipartisan IIJA was signed into law in 2021, proposing $1.2 trillion in funding for transportation spending, as well as broadband expansion, clean water, and electricity grid renewal. One of the stated aims of the IIJA was to reduce the impacts of climate change from the transportation sector, particularly from highways. But Transportation for America’s “Fueling the Crisis” report highlights the ways in which the IIJA has actually contributed to a business-as-usual approach, with states continuing to spend funds on highway expansion and resurfacing projects.

“It’s useful to think of every new highway or new lane like a new fossil fuel power plant, guaranteeing emissions for years to come from the additional miles of driving each will induce,” report author Corrigan Salerno wrote. “Over $37 billion in IIJA funding has gone toward new highways and wider roads. Using emissions increase and reduction output modeling figures from the GCC’s Transportation Investment Strategy Tool, these projects could induce the equivalent of more than 77 million cumulative metric tonnes of CO2e [climate] emissions above pre-IIJA baseline levels from 2022 and 2040. This is equivalent to the CO2e emissions produced from running 20 coal-fired power plants for a year.”

States continue to dwell on road expansion

The IIJA is structured in such a way that federal funding is provided to states, who have high levels of flexibility to determine how this funding is spent. This was seen by legislators as an opportunity to impact transport emissions for the better, depending on states’ investment decisions. But with modern Republican leaders largely denying that the climate crisis is real, and many Democratic leaders rating it a low priority, most states have continued a highway-centric approach, in line with the status quo.

Donald Trump once again being in charge at the federal level will likely mean even more focus on highways. This will also create headwinds for transit and safe streets projects, stalling fledgling progress on clean transportation.

The Biden Administration awarded Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity (RAISE) grants to multimodal and safety-focused projects on a much more frequent basis than the Trump-era predecessor. However, the larger Surface Transportation Block Grant program is more deferential to state priorities and continues to focus on highway expansion — a trend sure to increase under Trump.

The Biden administration released a fact sheet when the IIJA passed, stating that the legislation “will strengthen our nation’s resilience to extreme weather and climate change,” and that it would “help reduce our emissions by well over one gigaton this decade.” However, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) reported at the time that contrary to Biden’s statements, the IIJA framework seemed to reflect an “incremental rather than transformative approach,” partially due to the concessions made in pursuit of political agreement.

“The bipartisan deal,” wrote the CSIS, “Does far more for carbon-intensive roads and bridges than for fundamentally rethinking mobility,” an approach that would not lead to the climate-friendly outcomes touted by supporters of the law.

Three years after the IIJA came into force, analyses such as that from Transportation for America have now taken place that show the impacts of the legislation thus far. Contrary to the administration’s assertions and goals for the IIJA, the report is a damning picture of increased car-centric infrastructure: “States’ federal formula-funded investments made over the course of the IIJA could cumulatively increase emissions by nearly 190 million metric tonnes of emissions over baseline levels through 2040 from added driving.”

“This did not really come as a surprise,” Transportation for America’s Salerno told The Urbanist. “States have not really used that power to focus on carbon-emissions reduction projects, and instead we’ve seen states continue along the same path, if not slightly worse compared to previous years.”

The state of Texas was by far the leader in highway expansion and locking in climate pollution, followed by fellow Republican-led states of Florida, North Carolina, and Ohio, according to the report. However, Democratic governors did not prevent Pennsylvania and California from joining the list at 5th and 6th place in transportation emission gains, respectively.

The reasons behind these results are complex. In part, the carbon emissions reduction aspects of the IIJA are small, when compared to larger programs within the legislation. In addition, Salerno said, “The culture of planners and also, the political systems that we have, as well as how folks are rewarded for how they use transportation funds, tend to lead to more highway expansion projects.”

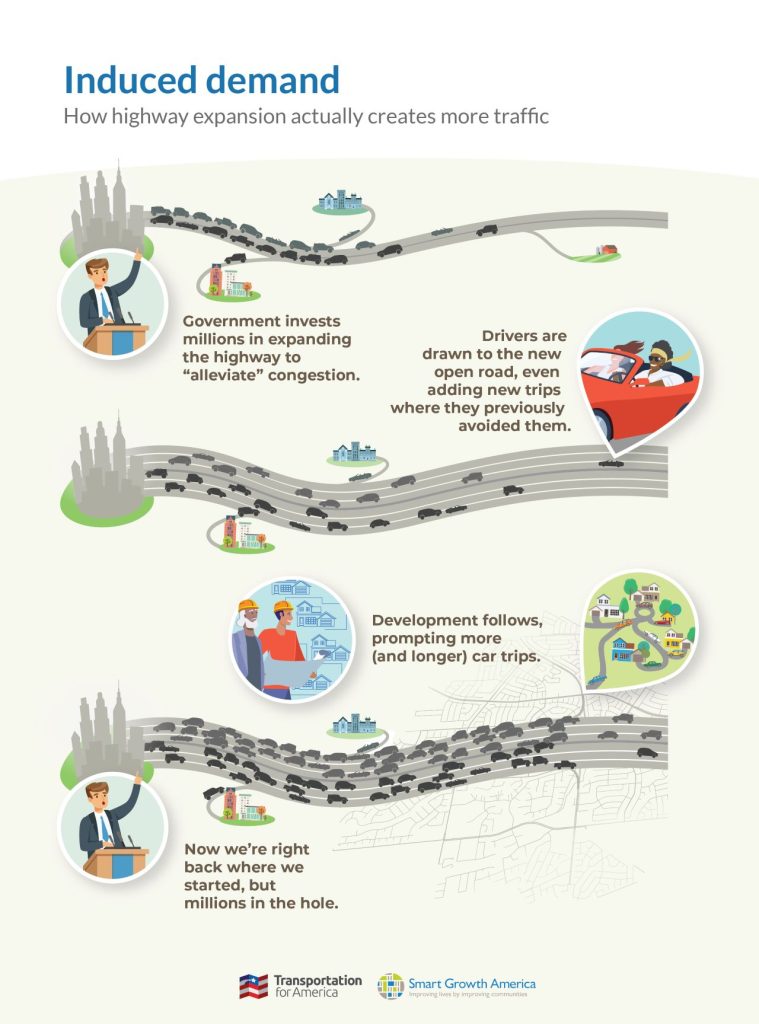

When many people are focused on car-centric transportation, using funds for highway expansion projects is seen as more politically expedient, and one way to solve the problem of congestion. This is despite significant evidence that expanding highways simply induces demand for more people to drive, and does not reduce congestion over the long run.

“The transportation system remains one of the most significant sources of greenhouse gas emissions in the US, but its emissions are projected to decline thanks to new policies from the Inflation Reduction Act,” the Transportation for America report states. “[But] those gains will be undercut if we continue to invest in projects that make driving the only viable mode of travel.”

In search of solutions

Transportation for America calls on policymakers to prioritize safety over speed, take a fix it first approach to roads, and invest in the rest: high quality transit, active transportation, and intercity passenger rail networks.

Fixing this problem and making wiser transportation investments will take “a whole of government approach,” Salerno said, and it could involve emission reduction requirements to nudge states to invest funds in a different direction. It could also take dedicated staff working on clean transportation and pedestrian safety.

“When you put those sort of priorities as part of someone’s job description,” Salerno said. “I think that’s when you start to see the change really begin culturally.”

With support from Governor Jay Inslee, a climate hawk, the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) has built out an active transportation division and sought to incorporate bike and pedestrian safety into more state road projects, with the state legislature adding a Complete Streets requirement to ensure investments are balanced.

WSDOT tapped Barb Chamberlain, a respected leader in the bicycling advocacy community, to lead the active transportation division. Chamberlain said the Complete Streets requirement has influenced how they spend IIJA funds and jumpstarted investment in street safety.

“The Complete Streets requirement includes a set-aside of a minimum of 2.5% of federal planning funds for state and MPO [Metropolitan Planning Organization] planning, standards, policies, prioritization, and active transportation plans.” Chamberlain said in an email. As a result, “Federal dollars will support projects that benefit active transportation,” she wrote.

Transportation for America’s analysis found that high emissions projects are particularly concentrated in suburban areas.

“Emissions tend to be where travel demand is,” Salerno said. “So the big loss is that there are these highway dollars that are going to these multi-billion dollar highway expansion-boondoggles, that could be going to building out infrastructure that supports active transportation and public transit options in more urbanized areas… “You’re giving the majority of people who already only have one option, more of the same.”

Some states have set a good example, such as Colorado and Minnesota, who have both recently passed new climate and transportation bills that will influence state spending in a more positive direction. Chamberlain also explains that some of the benefits of the IIJA for their work at WSDOT have been in areas other than emissions reductions.

“Updated language — this is small but significant,” she wrote, “An emphasis on safety showed up in updated policy language, new requirements for analysis and reporting, and dedicated funding in competitive programs. States now must set safety performance goals to reduce serious and fatal crashes.”

The new language and priorities have translated into active transportation projects faring better in the process.

“Active transportation facilities were included in many of the [recent] winning [RAISE] grants,” Chamberlain wrote. “And the criteria around safety and environmental benefits are places where inclusion of active transportation will help an application rank higher.”

Nonetheless, even with a climate-friendly governor, a new active transportation division, and a long run of Democratic control in the state legislature, Washington State continues to invest in highway expansion. The state’s IIJA investments show that the climate has suffered, overall. State leaders have made a $7.5 billion megaproject their top priority, despite mounting issues with the project. The project would both widen I-5 and replace the Columbia River bridge in Clark County.

Despite opportunities to dedicate RAISE grants to transit projects, the state has mostly favored road widenings. One of the Evergreen State’s largest recent RAISE grant recipients is a road expansion project in Lynnwood, near the city’s new light rail station. While the bridge will feature six car lanes, it includes the bare-minimum-standard sidewalks and bike lanes.

The need for organizing and advocacy

Transportation for America is stressing that states need to take more steps to invest in projects that reduce emissions. This is a process that needs to take place at all levels.

“I think it’s important that advocates [for active transport] should involve themselves as collaborators. This includes DOT work and work with city officials,” Salerno said. “You can be the change and involve yourself as a planner.”

A vitally important step is “identifying who are the advocates in existing state DOTs and city DOTs, and finding ways to empower them,” Salerno said. “I think it is crucial in moving the needle in these things because at the end of the day, it’s all people.”

Leah Hudson is an editor and writer published by Insider, Atlas Obscura, and Penguin Random House New Zealand. Leah loves to write about sustainable urban development, mental health, and matters of the heart. She spends her time reading, walking her dog, and eating unreasonable amounts of chocolate. You can find her at https://leahhudsonleva.com/.