With the fall public comment period on Seattle’s 20-year growth plan now closed, the Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) is preparing to send a finalized plan to the city council. But over recent weeks, groups of residents in neighborhoods throughout the city have been increasingly active in pushing to scale back the plan, and for additional housing capacity in Seattle’s lower density areas to be taken off the table.

The draft One Seattle Comprehensive Plan has been in the works since mid-2022 and has gone through several iterations to get to this point, and remains months behind schedule to meet the deadline imposed in the state’s Growth Management Act.

Most of the areas in contention are proposed “neighborhood centers” — a new type of land use designation that adds zoning capacity to existing commercial centers that already contain some community amenities. Narrowly focused, the neighborhood centers would only span a few blocks in places like Montlake, Georgetown, and Magnolia Village.

The Seattle Planning Commission, in a letter providing formal comment on the plan in mid-December, called for the neighborhood centers to be broader and allow even more density, but the local opposition is pushing for individual neighborhood centers to be wiped off the map, citing a litany of concerns, most of which apply broadly to additional density everywhere in the city. In keeping the neighborhood centers fairly limited, OPCD and the Harrell Administration have set them up as relatively easy targets for removal.

One of the first neighborhood groups to formally oppose one of the new centers was in Northeast Seattle, where a proposed Bryant neighborhood center would be added around a Metropolitan Market, close to the Burke-Gilman Trail and two bus lines. “While the move to increase housing availability is crucial for Seattle’s long-term sustainability, the selection of Bryant as a neighborhood center is misguided,” a Change.org petition created in early November states. “The proposed zoning changes will 1. Stretch our infrastructure beyond its limits 2. Compromise public safety 3. Harm the environment.”

One Seattle councilmember has already signaled potential alignment with the argument that the city hasn’t done enough to plan for investments in infrastructure. “[OPCD] has put forth its strategy for increased density without accompanying plans for transportation, utilities and other infrastructure, and climate goals,” District 4 Councilmember Maritza Rivera wrote in a newsletter sent out this past Friday. Rivera’s district encompasses both the proposed Bryant and Tangletown neighborhood centers, along with ones in Ravenna and Wedgwood.

“We need to take a holistic approach, per the Washington State Growth Management Act (GMA) which requires that comprehensive plans come with strategies for transportation, infrastructure, and climate resilience. I will be asking OPCD to give us information on how they will accommodate these needs,” Rivera continued. “OPCD is late in delivering the Comprehensive Plan and I have not seen preliminary strategies to accommodate infrastructure, transportation, and climate as part of their growth strategy.”

The Bryant petition was created by Addison Huddy, a Seattle resident with ties to the Hawthorne Hills Community Council. Located to the northeast of Bryant, the suburban-style Hawthorne Hills neighborhood was developed in the 1920s with a racially restrictive covenant that limited the sale of any home to a person “not of the White race,” and has one of the oldest community councils in the city.

In 2018, the Hawthorne Hills Community Council called on then-Mayor Jenny Durkan to step back from plans to add protected bike lanes to 35th Avenue NE through Wedgwood, citing the loss of parking spaces in line with a concerted “Save 35th Ave NE” campaign. Those bike lanes were ultimately cancelled, even though parking was also removed from the street to create a center turn lane. The letter they sent Durkan at the time stated that north-south “bike lanes should be located elsewhere.”

Save 35th Ave NE advocates then pointed to the 39th Avenue NE greenway, four blocks away down a steep hill, as the appropriate parallel bike facility. Now, members of the same community council point to the greenway’s presence as a justification to stop additional density. “With U.S. pedestrian deaths at a 40-year high in 2023, adding more cars to our streets will only make walking and biking more dangerous,” the current petition states. “39th Street is a 25ft wide street and a current Neighborhood Greenway. Imagine biking down a car-lined 25ft wide street.”

While the Hawthorne Hills Community Council didn’t seem concerned with the design of the greenway in 2018, most neighborhood greenways in the city have been constructed along narrow non-arterial streets with parking along both curbs, and 39th Avenue NE isn’t particularly anomalous in that regard. Among other arguments, the petition also cites vague issues that would apply to development anywhere in the city, including added strain on emergency services, sewer, and electricity.

Huddy’s petition is the only one so far that has seen a competing petition created asking the city to retain the Bryant neighborhood center in the plan, though plenty of comments on OPCD’s zoning map requested this as well.

Bryant’s neighborhood center is far from alone in being targeted for removal by nearby residents. Across town in Madrona, a neighborhood with a well-established commercial center up the hill from the Central District, a packed community meeting filled up a church hall on December 17 to discuss the proposed zoning changes. With no one on hand from OPCD to field questions, attendees shared their thoughts and concerns with the rezone maps and speakers, who included former Seattle Department of Neighborhoods Director Karen Gordon, did their best to answer questions.

After the meeting, OPCD’s zoning map was flooded with comments pushing for a rollback of changes in Madrona, which include both a neighborhood center and proposed upzones along the King County Metro Route 2 heading down to Lake Washington.

“Madrona does not rise to the standard of being an urban village; it is a mostly single-family residential neighborhood with a 2-block-long strip of small restaurants and shops and no daily-needs amenities. It is missing much of the critical infrastructure to make the transition to a significant up-zone tenable, or to serve resident needs locally,” a group of realtors identifying themselves as Madrona residents wrote in a letter to Mayor Bruce Harrell on December 16.

The letter asks the city to consider other areas for density, including nearby MLK Jr Way S, a street on the Seattle Department of Transportation’s (SDOT) high-injury network map due to the prevalence of serious traffic crashes on the corridor.

In North Seattle, neighborhood groups with a history of attempting to block new development have also become active around these proposed rezones.

“Urgent: Help Save Green Lake from 5-story Apartment zoning with no parking required,” read the subject line in an email sent to attendees of a joint meeting of the Green Lake and Phinney Ridge Community Councils on December 3. The sender was Bob Morgan, a Phinney Ridge homeowner who, in 2018, filed an appeal against a council-approved rezone paving the way for Shared Roof, a 35-unit communal apartment building that has attracted retail tenants like Doe Bay Wine Company and Lioness restaurant. Morgan’s ultimately unsuccessful appeal in King County Superior Court alleged that approving the project would “cause irreparable harm” to “the entire Phinney Ridge neighborhood.”

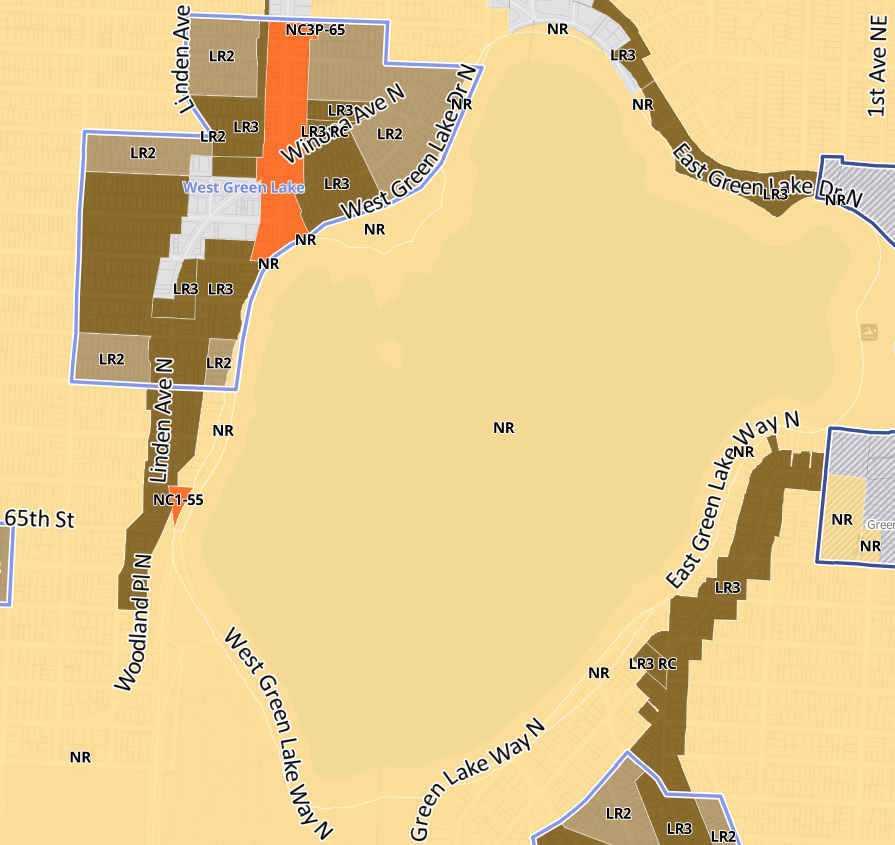

OPCD’s rezone proposal includes a sizable new neighborhood center around West Green Lake, along either side of Aurora Avenue N and its RapidRide E line but extending beyond just the parcels fronting the state highway. Morgan’s email this month was brief, and encouraged recipients to contact OPCD and the mayor to withdraw proposals for both the West Green Lake neighborhood center, and for upzones along the route of the Route 45 and 62 buses on the other side of Green Lake.

“I think our neighborhood residential areas are going to become unrecognizable,” Morgan said at that December 3 joint community council meeting, co-hosted by the Phinney Ridge Council’s Alice Poggi and the Green Lake Council’s Shana Kelly. “Part of this is the theory that somehow builders will build an oversupply of units, and the price will come down, and it will make the city more affordable for everyone. […] the private market is not going to produce affordable housing through oversupply. That’s been proven. We’ve watched it, it hasn’t happened.”

While gospel among Seattle’s neighborhood advocates, the idea that building more housing won’t reduce prices market-wide is refuted by numerous studies and examples, with housing prices in Austin, Texas dropping year-over-year in response to sustained building following housing reforms. Minneapolis, Minnesota provides another recent example.

By the time the Seattle City Council convenes for the first meeting of the Select Committee on the Comprehensive Plan on January 6, a group of residents from every single council district will have been pushing for proposed zoning changes in their area to be significantly scaled back, all using similar arguments around lack of infrastructure and loss of neighborhood character. Beyond the aforementioned neighborhood pushes are campaigns in Mount Baker, Fauntleroy, Magnolia, Whittier, Maple Leaf, Greenwood, Montlake and Queen Anne.

While OPCD may have made tweaks the overall plan by that time, it will almost certainly be Seattle’s nine councilmembers who will be tasked with deciding whether to cede to these requests or hold steady on Mayor Harrell’s growth plan. With chair Tammy Morales’ resignation, District 3 Councilmember Joy Hollingsworth will take over leadership of the Select Committee on the Comprehensive Plan.

Already the Comprehensive Plan is structured to encourage synergy between housing and other infrastructure. Earlier this year, the Council unanimously approved an expansive citywide transportation plan, with an implementation plan for the first few years of Seattle’s new transportation levy on the way in 2025. In addition, the draft One Seattle plan includes full chapters on capital facilities, utilities, and transportation, as required by state law.

While Seattle has elected councilmembers via district-based elections since 2015, the current council has taken additional steps to give deference to issues that impact their colleagues’ districts. The most egregious example was approving a $2 million proviso to modify the RapidRide H Line project to remove a left-turn restriction on Delridge Way SW in District 1 Councilmember Rob Saka’s district.

Whether the same level of district deference carries forward into this plan will be something to watch. While the neighborhood centers are riling up housing opponents at the district level, they’re proposed in response to a citywide housing shortage and affordability crisis.

The council’s select committee will begin digging into the plan over its January meetings ahead of a public hearing on February 5 at 5pm. The city council is accepting email comments on the One Seattle plan through that time at council@seattle.gov.

A previous version of this article listed an incorrect date for the February public hearing.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.