A multi-billion dollar shortfall is forcing a choice between doubling down on highway expansion or a new path.

Ahead of the 2025 legislative session, a significant amount of focus is on the more than $12 billion deficit in the state’s operating budget projected over the next four years, a significant task for lawmakers to deal with over their 105 days. But lurking behind problems with the operating budget is a more systemic issue that’s set to come to a head this year: the long-term sustainability of the state’s transportation budget.

With a $14.6 billion allotted for the current biennium, Washington’s transportation budget ensures more than 7,000 miles of state highways keep functioning, keeps Washington State Ferries moving, and provides funding for a range of multimodal transportation options, including airports, Amtrak Cascades and freight railroads, and local bike and pedestrian projects. Also included in the transportation budget are agencies like Washington State Patrol and the state’s Department of Licensing.

Declining transportation revenue and increased project costs are clashing directly into long-promised highway projects and other state commitments, with badly needed investments in transit, active transportation, and traffic safety all fighting for a seat at the table. A state senate transportation committee staff presentation earlier this month detailed a budget gap of at least $6.5 billion through 2031, if significant action isn’t taken.

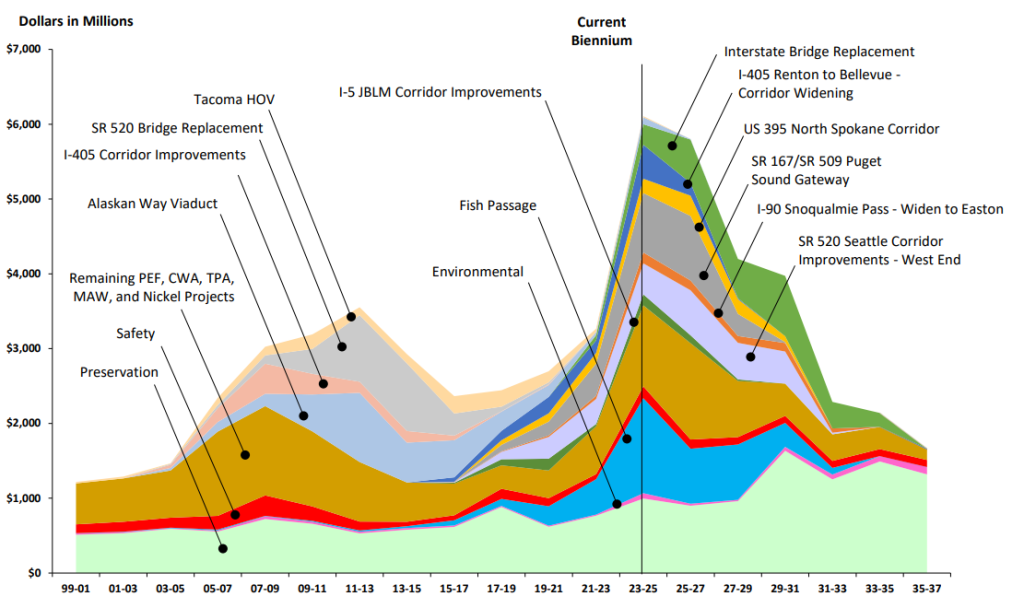

The crisis has been building for years. Despite state climate goals, the long-term solvency of the transportation budget has long depended on Washington’s gasoline tax, with forecasts — as recently as earlier this year — projecting the state to continue to increase overall gas usage in perpetuity. In 2003, 2005, 2015 and 2019, the state legislature bonded against motor vehicle fuel taxes, which include those on gas and diesel, to provide funding for transportation packages that largely focused on expanding the state highway network. The most recent 2019 bond issue approved to move up the timeline for the I-405 widening on the Eastside and the Puget Sound Gateway highway extension projects.

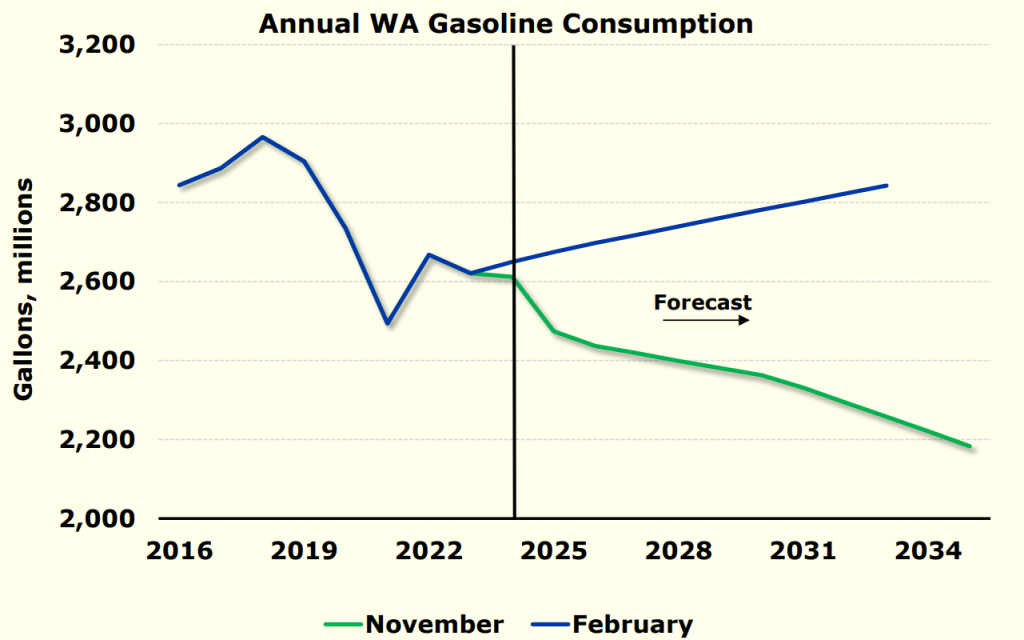

After years of rosy forecasts of future gas tax revenues, a new reality is starting to set in, prompted by a new revenue forecast model created by the Washington Economic and Revenue Forecast Council, which took over modeling transportation revenue after a 2023 change in state law. That new model is good news for the climate, and bad news for the gas-tax-centric transportation budget. It assumes that Washington hit peak gas consumption in 2018, with vehicle electrification and post-pandemic travel habits set to equate to declining gas usage moving forward.

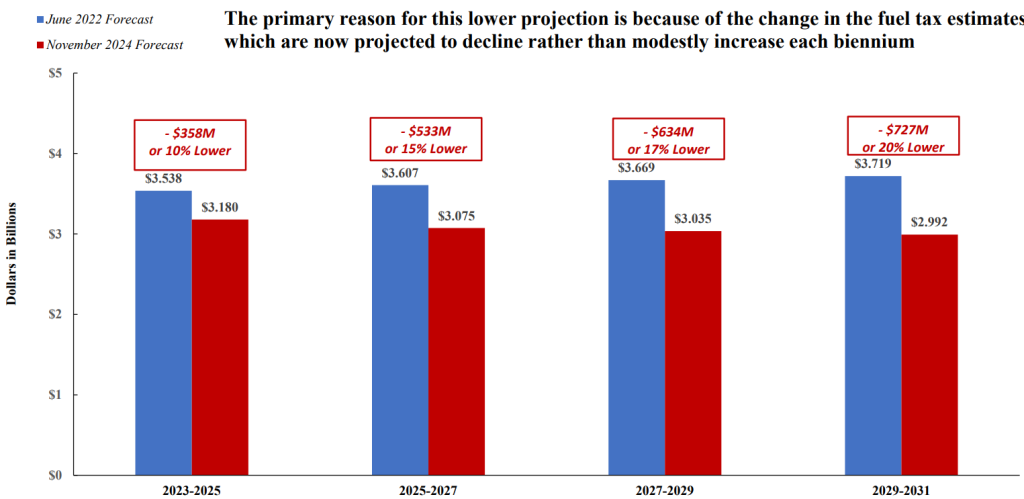

Compared to the gas tax forecasts that were used to put together the 2022 Move Ahead Washington transportation package, the state is now projected to bring in 10% less revenue from fuel taxes over the current biennium. The erosion of gas tax revenues escalates to 20% less in the 2029-2031 biennium — this downward trend translates to $2.2 billion simply evaporating over eight years. At the same time, gas tax revenue is still funding debt service on past transportation packages, leaving even less for current projects. By 2025, 75% of total gas tax revenue is expected to go toward debt service, according to a Puget Sound Regional Council presentation earlier this month.

Governor Jay Inslee’s budget, released last week, doesn’t offer much help when it comes to long-term solutions. While Inslee has proposed progressive revenue sources like a 1% wealth tax and an increase in the state’s business and operations (B&O) tax to aid in balancing the operating budget without massive cuts, his budget actually increases the deficit projected in the transportation budget for the 2027-2029 biennium, leaving the really tough decisions to incoming Governor Bob Ferguson and the legislature.

The Governor’s budget proposal makes it clear that the Senate and House transportation committees have a lot of work to do. “A funding gap for highway projects will require legislators to explore options to adjust delivery timelines or funding,” it notes.

Climate Commitment Act revenue isn’t meeting expectations

Separate from the gas tax’s new normal, storm clouds are also brewing when it comes another major source of transportation funding, the Climate Commitment Act (CCA). The landmark 2021 climate law that created a second-in-the-nation cap-and-invest program, the CCA is the primary source of revenue for Move Ahead Washington projects that aren’t focused on highway capacity — including a long list of bike and pedestrian projects in every corner of the state and the biggest state-level investment in public transit in decades.

Those multimodal projects are clearly popular with voters, given the fact that Initiative 2117, a measure that would have repealed the CCA and cancelled all future carbon auctions, failed spectacularly during November’s election. A majority of voters in 24 of 39 counties rejected the idea of getting rid of the CCA, but what investments it will be able to fund depends entirely on the amount of revenue generated at auction.

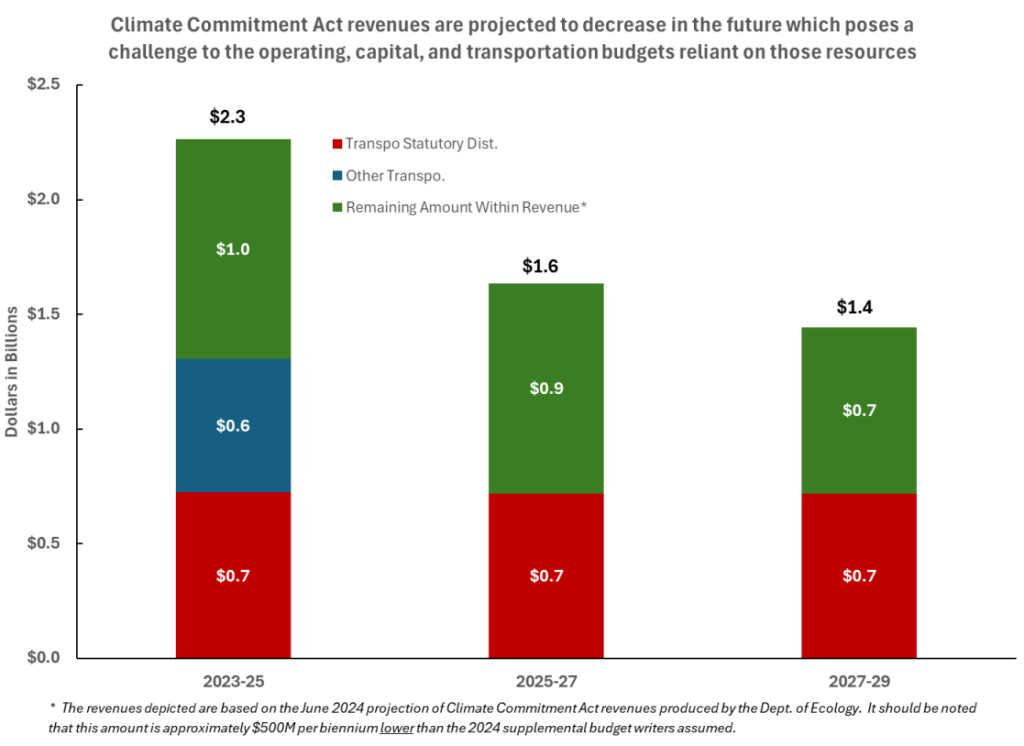

All three of Washington’s state budgets — operating, capital, and transportation — receive revenue from the CCA, but it’s the transportation budget where revenues are directed first, by law, to be used to decarbonize the state’s transportation system. Currently, the CCA is funding around 9% of the state transportation budget. Though the most recent carbon auction garnered a per-ton price that’s up over the previous auction earlier this year, those prices are still below what was assumed when the Move Ahead Washington package was being assembled in 2022, by around a half billion dollars per biennium.

Original projections assumed that the CCA would bring in $2.8 billion over the current 2023-2025 biennium, but auctions are now projected to bring in just $2.3 billion, with a similar drop in the forecast for the 2025-2027 biennium, from $2.1 billion to $1.6 billion. If that trend holds, it makes the promises included in Move Ahead Washington, such as $50 million in upgrades for North Seattle’s stretch of Aurora Avenue and $25 million for Bremerton’s Warren Avenue bridge, harder to fulfill.

A planned linkage with the carbon markets in California and Quebec, introduced partially in response to complaints that the CCA was impacting Washington’s gasoline prices, has the potential to keep that per-ton price low, forcing lawmakers to either delay projects or find a way to make up the difference.

“You have an underlying problem, and this is a budget problem/challenge for the three budgets collectively to determine how to solve,” Byron Moore, a policy analyst with the senate transportation committee, told lawmakers early this month in breaking down the $500 million projected shortfall per biennium. “So that’s one issue which I’d characterize as more of an immediate problem, and then you can also see that regardless of that challenge, the Climate Commitment Act dollars are projected to decline over time going forward, which creates additional pressure in terms of the spending that’s associated, on all three budgets.”

The shortfall in CCA revenue suggests that transit, bike, pedestrian, and ferry funding could also see cuts or project delays if the state isn’t able to find a viable path forward.

Project cost increases continue to stack up

On top of declining revenue is another mounting issue that lawmakers will finally have to reckon with: skyrocketing price increases impacting highway expansion projects. This trend is starkly illustrated by the SR 520 Portage Bay Bridge and Roanoke Lid project in Seattle, which saw its total cost increase 70% over initial estimates when it went to bid last year. Highway megaprojects around the state are all costing much more than the state originally assumed they would.

With highway spending already at its highest level in decades, the cost increases are poised to add at least another $1 billion to the transportation budget’s balance sheet — and those are just the increases we know about. On top of an additional $271 million for the North Spokane Corridor, $335 million for the widening of US 12 near Walla Walla, and $155 million for the Puget Sound Gateway, risk assessments still haven’t been released for other megaprojects including the I-5 Interstate Bridge Replacement in Clark County, which is set to be the most expensive project in Pacific Northwest history. Even though the State of Oregon — despite significant budget issues of its own — has committed $1 billion to the bridge, the project is still not fully funded as it heads toward a groundbreaking targeted for 2026 or 2027.

On top of that, the state still needs to find a way to fund an additional $5 billion in culvert replacements along highways across the state, a requirement that stems from a 2001 lawsuit seeking to improve fish passage to aid salmon recovery. So far WSDOT has been able to complete 50% of the required barrier removal, but the work that remains is set to be exponentially more expensive on a per-culvert basis. Nonetheless, the agency faces a deadline of 2030 to install 90% of the culverts covered under the court order.

All that is happening against a backdrop of a state transportation budget that has prioritized expansion projects over basic maintenance and preservation for at least two decades. WSDOT estimates a $1.5 billion per year shortfall between existing revenue and what’s needed to keep the transportation system in a state of good repair. The state is facing significant maintenance needs in every corner of the state, yet maintenance and preservation have only accounted for around 10% of the transportation budget in recent years.

The cherry on top is the incoming Trump administration, which is almost certainly going to reassess federal spending priorities when it comes to transportation. The first Trump administration slashed transit grants and failed to pass a major infrastructure bill. Move Ahead Washington assumed the state would be able to win $650 million in competitive federal grants over its 16 years, but some of that spending is poised to evaporate over the next four years.

What to do about revenue?

Facing budget pressures from all sides, the search for potential new transportation revenue sources is expected to be a major focus in 2025, but the number of options available to legislators isn’t huge. The goal of a permanent replacement for the gas tax, in the form of a per-mile Road Usage Charge (RUC) that treats all vehicles equally regardless of fuel efficiency, still looks to be heavy lift. The state has been exploring the idea in some form since 2011, with the Washington Transportation Commission continuing to develop recommendations on what a program would look, but it’s still unclear whether lawmakers are ready to tackle the issue.

A bill implementing a voluntary RUC, aligned with Oregon’s existing program, failed to advance out of committee in 2023 and wasn’t even discussed during the 2024 session. However, the stark reality of gas tax revenue declining even faster than policymakers had expected might be a strong impetus toward action in 2025. Marko Liias, chair of the Senate’s transportation committee, told KING 5 earlier this year that lawmakers needed to start discussing the idea, after stating that a direct increase to the state’s gas tax is at the bottom of his list of preferred revenue options.

While the state’s gas tax is directly tied to “highway purposes” thanks to a 1944 amendment to the state constitution, a RUC wouldn’t face the same constitutional restrictions. Though some lawmakers want to write similar highway-only restrictions into law, the proposed RUC could provide a direct way to fund badly needed multimodal investments around the state, not just those tied to the state highway network.

Other ideas are percolating. A study looking at a potential fee on retail delivery orders found that 30 cents per delivery could generate an additional $45 to $112 million by 2026, growing to as much as $160 million by 2030. Such a fee is already in place in Colorado, with the fee indexed to inflation to ensure the revenue source doesn’t diminish over time. But in a year when the legislature is already set to examine numerous new tax proposals to aid the operating budget, new transportation revenue options face significant headwinds.

Another option set to get more attention this session is the idea of dedicating the portion of state sales tax generated by the sale of motor vehicles to transportation. A pet issue on the Republican side of the aisle for years, that proposal ultimately doesn’t advance the state very far and ultimately just reallocates funding from other areas that are struggling, including schools and mental healthcare.

Ultimately, if the legislature does decide to use additional revenue to shore up highway projects while leaving maintenance, preservation, and safety out in the cold, that will do very little to alleviate the long-term issues with the state transportation system. In remarks delivered this month, outgoing WSDOT Secretary Roger Millar offered a foreboding warning about continuing to disinvest in maintenance.

“I am concerned, absent investment in maintenance and preservation and safety and operations, our system will not be reliable,” Millar said. “All I need to do is have one bridge on I-90 between Idaho and Seattle become load-restricted, and every truck on that highway will no longer be able to be loaded 80,000 pounds. The same thing on I-5, and that is coming.”

While significant cuts are certainly on the table as legislators consider their options, a full realignment of the state’s transportation budget could offer an opportunity to bring state spending in line with its climate goals. That would entail far greater focus on maintenance over highway expansion and providing funding for options that allow people to get around without cars. Doubling down on the highway project list is one way to ensure that the can is simply kicked further down the road.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.