In a 5-1 vote Monday, the Bellingham City Council backed Mayor Kim Lund’s plan to end parking mandates citywide as part of her multi-pronged strategy to boost housing production. The vote signaled support for Mayor Lund’s broader strategy, which includes pursuing allowing sixplexes citywide on a faster timeline than required by the state and streamlining the permitting process.

On November 21, Lund issued an executive order directing City departments to take immediate actions to increase housing opportunities in Bellingham and pushed a package of reforms with the city council. Lund was elected in 2023 on a pro-housing platform, and appears intent on making good on those campaign pledges to ease the housing crisis. On December 9, Lund presented her executive order and associated legislation to Bellingham City Council. Monday’s committee vote will be followed by a full council vote in early January, but the vote is all but certain.

“The executive order is about taking immediate actions across the city that are within the city’s control to reduce these barriers that are getting in the way of expanding housing opportunities in Bellingham, and that many of these changes must happen in the coming years, because they are required by state law,” Lund told Council. “Yet I believe we can do much of the important work more quickly. So, much of the intention behind the executive order is to accelerate these actions, because we do not want our community to wait longer than necessary for action, and so we are proactively jumpstarting this process.”

Housing cost increases are outstripping wage growth and inflation, leading a majority of Bellingham renters to be cost-burdened, Lund noted.

“We’ve reached a critical point for housing affordability in Bellingham,” Lund said in her executive order. “Over the years, housing costs have increased, and incomes haven’t kept pace. In the last five years, the median rent in Bellingham has increased by 37% and the median home price by 56%. Additionally, 24% of homeowners and 56% of renters are cost-burdened, meaning more than 30% of their income goes toward housing. This order is designed to increase the supply of housing, which can increase vacancy rates and, in turn, helps keep rents and home values from rising – or even reduces them.”

Bellingham’s Director of Planning and Community Development Blake Lyon shared similar stats and sentiments during his presentation to Council laying out the case for ending parking mandates.

“Housing the people of this community, providing them choices and options, is far better than housing vehicles,” Lyon said. “[I] would much rather come to this topic with a way to provide housing for somebody and a range of people in this community, and giving that choice back to the members of this community at a variety of different [income] ranges.”

Councilmember Lisa Anderson (Ward 5) was the only vote against the interim ordinance ending parking mandates. Anderson doubted that lowering parking costs would lead to lower rents for tenants, and she argued for inclusionary zoning, requiring developers to provide affordable homes in new projects, and hinted at rent control being the better method to force more affordable homes into the market.

“The reality is that we live in a capitalism society; that’s our economy,” Anderson said. “And even though a developer might be able to save money, I think there’s this like sense that people in the community believe that’s going to lead to potentially lower rent. And things are always market rate, and the only way that we’re going to have potentially lower rent for some of these units is if we require it.”

Meanwhile, Councilmember Michael Lilliquist (Ward 6) abstained after a long monologue criticizing supply-side housing economics and expressing a desire to see a more “nuanced” and surgical policy that unburdened affordable housing from parking requirements, but perhaps left them in place elsewhere.

“What I would submit to you is that scarcity is absolutely a simple and known impact,” Lyon said, in response to Lilliquist’s comments. “Not having units in the market drives up costs as simple as that statement. So you’re absolutely right that there are some complexities, and there are variables that go into what it takes to produce those units. Not having those units, the effect of not having those units is absolutely known and has been experienced. And when we talk about that middle housing component, eliminating parking benefits those affordable units too.”

While supporters of parking reform acknowledged the policy was no silver bullet, they ultimately pointed to the benefit of reducing building costs and encouraging homebuilding with the tools they have.

Councilmember Hollie Huthman (Ward 2) noted she got into politics due to seeing friends being priced out of the city by rising rents. She also pointed to a case study showing the success of lifting parking mandates in Minneapolis and another showing that easing parking requirements and unbundling parking costs in a recently built Bellingham apartment building helped reduce housing costs, particularly for the half of tenants that went without parking. The project likely wouldn’t have happened without lifting the parking mandate.

“When it when it comes to parking, none of it, none of it is free,” Huthman said. “Every parking spot has a cost. If you are a renter and you have a parking spot, you are paying for that parking spot, whether you know it or not, unless your unit has parking unbundled so [that] you pay separately for parking. So, those are two examples that I find to be really compelling to support this move.”

Minneapolis has seen some of the slowest rent growth in the country, and Huthman noted Minneapolis implemented a package of reforms very similar to the executive order that Lund is advancing in Bellingham — through Bellingham has not pursued parking maximums like Minneapolis has. As council president pro tempore, Huthman led Monday’s meeting, with Council President Daniel Hammill attending virtually due to an illness.

“Obviously, I am the first to insist that supply alone is not a panacea for every problem in our housing market,” Councilmember Jace Cotton (At-Large) said. “But I also know if we don’t rapidly increase supply, there is no hope that this community can be a place that’s affordable for working people in the decades to come.”

Once approved by a full council (rather than committee) vote, the interim ordinance will last for one year, allowing the City of Bellingham time to put a permanent parking ordinance in place. Council can extend the interim ordinance beyond the one-year pilot in six-month increments, but the City must hold a public hearing before granting each extension. Utilizing the tool of an interim ordinance follows the path that Port Townsend took earlier this year, and allows cities to act more nimbly.

Like it has in Spokane, Bellingham’s swift actions to spur homebuilding and implement parking reform show what is possible when the mayor, council, and city staff are aligned. Seattle has never had the same synergy. Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell and his centrist predecessors have been hesitant to rock the boat by eliminating restrictive single family zoning and parking mandates citywide and encouraging transit-oriented development near all major bus lines. Hence, Seattle is planning to continue to require parking and limit development to townhomes in much of the city, despite being a leader in earlier parking reforms that ended residential parking mandates in urban centers when passed in 2012 and doubled down on in 2018.

Pro-housing reform like ending parking mandates and eliminating single family zoning are in vogue. Cities like Portland, Minneapolis, San Francisco, and Austin have ditched parking mandates, as have an increasing number of Washington cities, including Spokane, Port Townsend, and most recently Shoreline, which also took the parking plunge Monday. Cities nationwide are racing to address their festering issues around housing and reverse perceptions that Democrat-run cities are poorly run and too adverse to new housing.

Some pundits, such as Ezra Klein and Seattle’s own Dan Savage, have even suggested that Democrats are slowly sabotaging their electoral prospects at the federal level by obstructing housing and advancing slow-growth policies while red states juice their population with rapid housing growth (albeit often of a more sprawling, car-oriented variety). Some even contend that rising housing costs and associated problems (like homelessness) have shaken voters’ confidence with Democratic leadership, providing an opening that Trump has twice seized upon.

However, Bellingham housing advocate Jamin Agosti told The Urbanist that Lund and her allies on Council were poised to pursue housing reform regardless of presidential election results. The executive order was the culmination of much earlier ground work, including at the Bellingham Planning Commission, where parking reform has been on the docket.

“I don’t think it’s based on national politics. I definitely get the impression this is something that she would have done anyway,” Agosti said. “She campaigned on housing. She’s been talking about housing ever since she was elected, ever since she started campaigning. And I think this is a priority-setting movement for her really directing staff, and signaling to the public that this is what’s coming next, and putting a little bit of pressure on community groups and and city council to put the money where their mouth is.”

As a city of 97,270 residents at the state’s last estimate, Bellingham can face challenges attracting investors often necessary to build large residential projects. Rents and prevailing wages are not as high as in the Seattle metropolitan area, often leaving homebuilders with tight margins.

“I think we have a pretty unified city council here in terms of being open to promoting density and promoting infill development,” Agosti said. “We’re not going to get 30-story skyscrapers and we’re and we’re not having the kind of the same conversations that Seattle is having… It’s really, how do we promote investment in Bellingham, where we’re not currently getting it right? We’re fighting for homeowners and developers to come and build. And the question really is: Where can we get it, and can we get it in a way that kind of aligns with our community goals?”

Like many cities, the pandemic led to new housing pressures. Situated snugly between Puget Sound and the foothills of towering Mount Baker, Bellingham was a popular outlet for remote workers looking for more scenic settings in the work-from-home era. This diaspora likely contributed to price pressures in the city.

“There’s absolutely a trend of West Coast diaspora, of high paying professional jobs that impacted affordability in Bellingham. No question,” Agosti said. “You only have so many levers to control affordability and production is really one of the strongest levers you have as city government. So I’m glad to see that the mayor and is leaning into that, even if it’s not a silver bullet to the affordability crisis. It’s unlikely that market-rate housing is going to provide housing that everyone in Bellingham needs, but hopefully it’ll take some of the pressure off if we can get to a point where we’re actually meeting our housing targets.”

Lund’s order alluded to the need to provide public subsidy for housing serving the lowest income households: “Some housing types, such as permanently affordable housing or transitional housing (like tiny home villages), need unique partnerships that the City has a role to cultivate and fund.”

But making it easier to build housing in general is a necessary step in the eyes of Lund and most on the Bellingham City Council. Moreover, they argue residents are asking for these changes, pointing to outreach conducted for the Bellingham Comprehensive Plan.

“Our community is asking for this change,” Lund said in the press release accompanying her executive order. “In our recent engagement with the community on the Bellingham Plan, we heard clearly that people want all neighborhoods across the city to have more housing, with choices for everyone and a variety of housing types.”

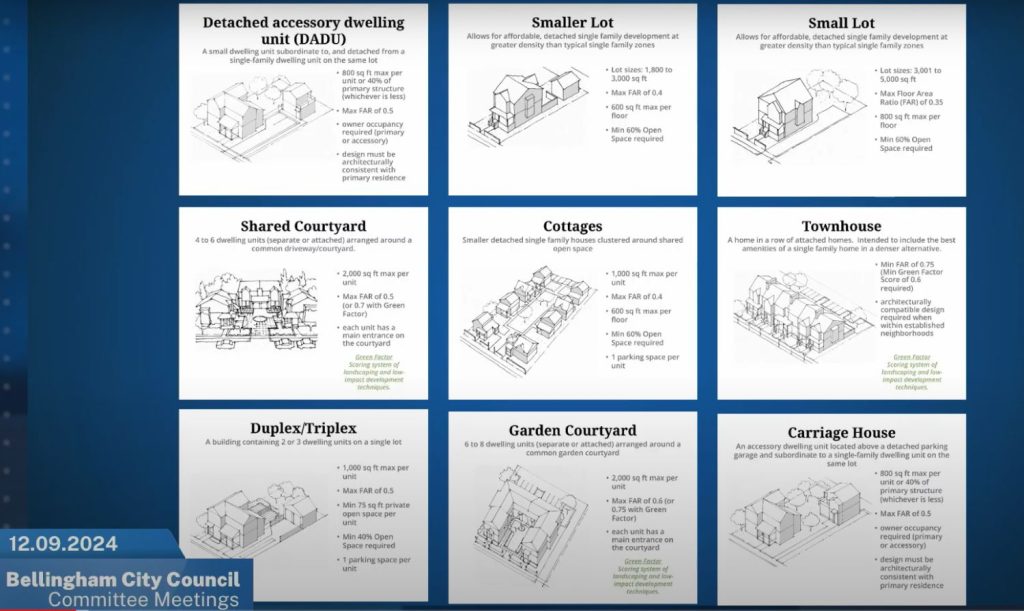

Next up in Lund’s housing plan will be encouraging “missing middle” housing in the vast swaths of Bellingham currently dedicated to single family homes. Middle housing types can range from accessory dwelling units (ADUs) to townhomes and even small apartment buildings. While central Puget Sound cities have until mid-2025 to comply with House Bill 1110, the middle housing bill the Washington legislature passed in 2023, Whatcom County cities have another year.

“We need more housing overall, and more options that are within reach for people of all incomes,” Lund wrote. “Currently, 75 percent of land zoned as residential in Bellingham is developed with single-family housing. Building more ‘middle’ housing types – ADUs, townhomes, duplexes and other small multi-family housing types – is an essential part of helping us achieve our community’s shared goals for more, denser, and affordable housing.”

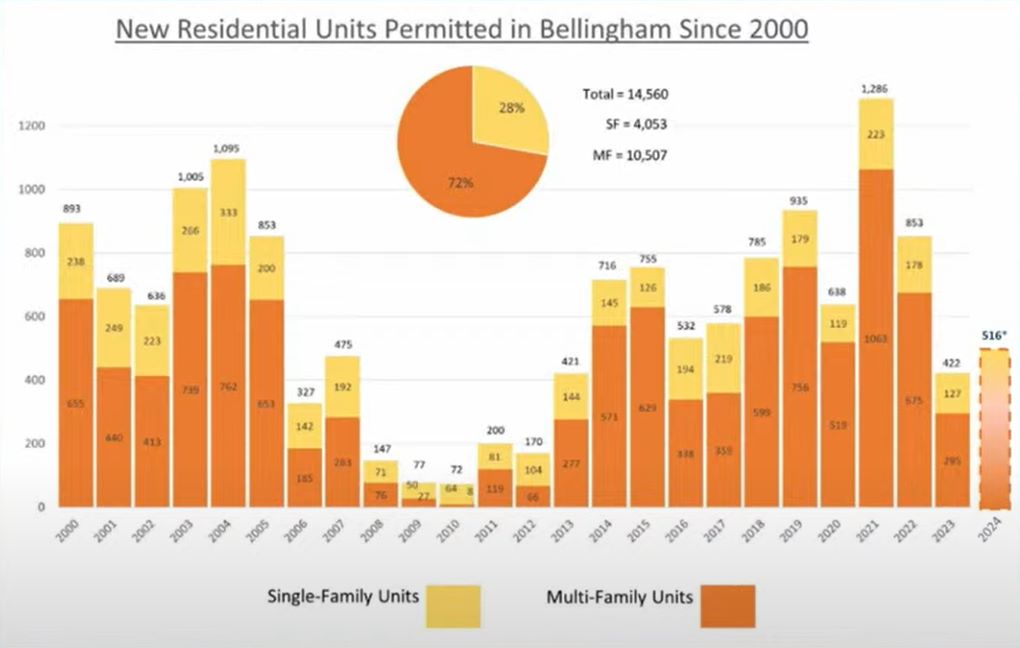

While Bellingham has sought to encourage infill housing like ADUs since 2009, production has been pretty modest. Parking mandates and other onerous regulations getting in the way is one big reason. Bellingham has tackled part of the problem, and leaders are hoping homebuilding will pick up the pace.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.