Earlier this year, Mount Rainier National Park launched a pilot timed-entry reservation system as an initial effort to manage burgeoning park visitation. Reception was lukewarm around Puget Sound, and continues to be the subject of frustration, including this recent suggestion that Washington residents should enjoy priority access to the park. These feelings are understandable — it’s human nature to grouse when something that we so easily enjoy gets a little less convenient to access and wish to keep it for ourselves.

But timed entry is a real improvement over the free-for-all that used to be a visit to the park — a long drive to the entrance with unpredictable, potentially hours-long waits for enough visitors to depart before rangers could allow others entry. Crowding at parking lots adds another huge headache in the free-for-all scenario.

The timed-entry system would work even better if paired with a robust public transit network to serve Mount Rainier National Park’s primary destinations. That would unlock Mount Rainier (or Taquoma as it’s known to the Puyallup Tribe, who have lived near the mountain since time immemorial) to more visitors, while improving environmental sustainability.

Surely we value our transcendent outdoor spaces enough to plan ahead or spend an additional 20 or 30 minutes getting to these destinations to commune with them. Investing these modest amounts of time is a small price to pay for limiting the human and in particular the automobile impacts to the park.

Those of us fortunate enough to have chosen to live here or grown up in this glorious part of the world of course feel a special bond with it. Rather than privileging Washington residents over visitors by prioritizing our personal access, however, our experience of deep connection is best harnessed to share our appreciation, knowledge, and sense of responsibility to care for and protect it. After all, our national parks are for everyone.

For many Washingtonians, the kind of easy access that opponents of timed entry describe is not the norm. Those of us who cannot drive don’t have the privilege of hopping in the car and heading off to Paradise. About one-third of Washington residents cannot drive themselves, and this subset is more likely to have a disability, low income, or be people of color.

Those of us in this nondriver category — two of the three authors — share the same love and value of our mountains, trails, lakes, prairies, and shorelines as so many Washingtonians, but we cannot travel to these, including Mount Rainier, with anything like the ease that our neighbors are accustomed to, because we cannot get to most of them — period. Coordinating schedules and logistics with friends who have cars is nearly impossible, especially when it comes to trips with kids. Transit access to the park would change that.

Public transit would offer a more inclusive vision for improving access to the park that would better protect and preserve it. Transit service to and throughout the park would profoundly expand access for our state’s substantial population of nondrivers, and nondriver visitors to Washington. Many people — residents and visitors alike — who can drive would prefer to take transit to outdoor destinations. King County’s highly successful Trailhead Direct program bears this out. In this era of climate and environmental degradation, we should be doing all we can to make choosing transit as easy as possible.

Fortunately, there are many models for transit service to and in our National Parks we can draw on. The Grand Canyon can be enjoyed wholly by bus. Yosemite is served by the Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System (YARTS) that brings people from all over the nearby region to the park, as well as an internal shuttle system. Even remote Denali can be reached by train and has several tiers of bus service inside the park that cater to a range of visitors. Canada’s Banff National Park recently opted to shift the access policy to its wildly popular Lake Louise and Moraine Lake areas by prioritizing transit, shuttle, and bicycle entry while limiting private vehicle entry.

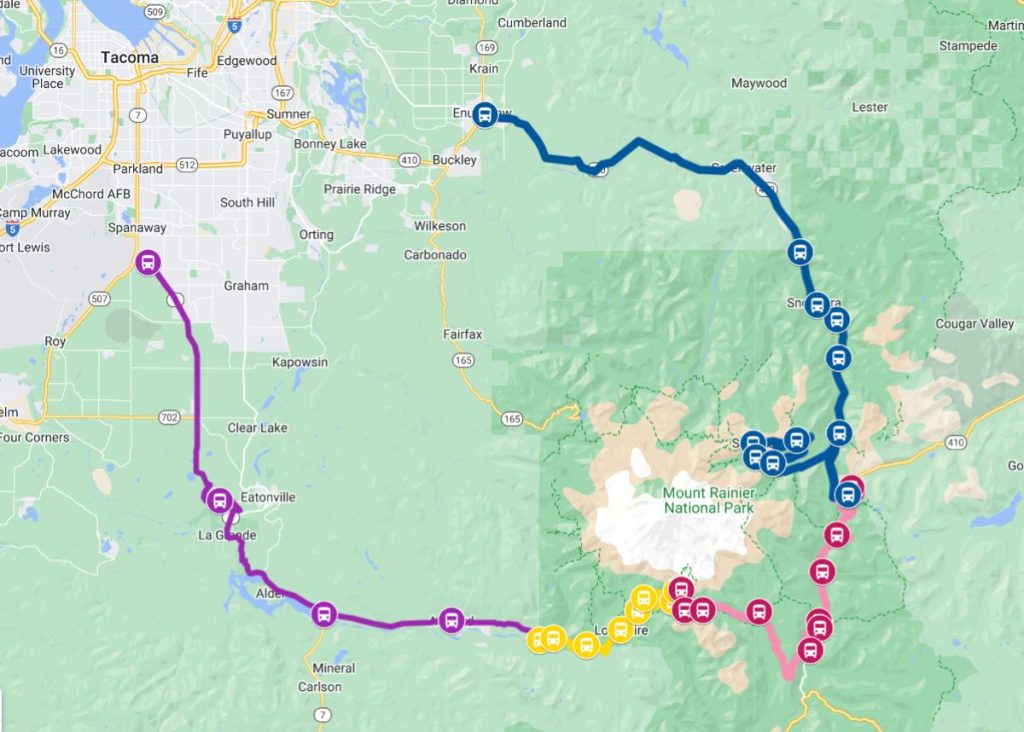

We urge regional governments and the park service to invest in expansive, year-round public transit, to establish affordable, accessible travel from population centers to the park. A system akin to YARTS and Yosemite’s internal shuttles seem best suited for Mount Rainier. Such a system could:

- Increase access to the park for nondrivers and those who wish to leave the car at home, whether these visitors come from as near as Seattle or as far as the other side of the world;

- Allow park management to redirect some resources away from traffic management;

- Offer much-needed transit service to rural communities that border the park;

- Reduce traffic impacts to those same rural communities;

- Curb demand for timed entry slots, offering a better shot for those who must drive to the park;

- Reduce parking overflow near trailheads;

- Offer new ways to enjoy point-to-point hikes without the hassle of staging multiple vehicles;

- Reduce traffic collisions (public transit is much safer on average than traveling by car), including collisions with animals; and

- Reduce climate and microplastic impacts from cars and their tires.

There’s simply no other solution that comes close to producing so many returns on investment.

Mount Rainier feels like it’s in our backyard, but for people that can’t drive, it’s impossible to access today. Robust public transit service would provide access for everyone and generate many positive side effects. As we plan the future of our national parks and regional transportation system, let’s make sure all of us can enjoy Paradise.