While Kirkland’s growth plan was ultimately watered down, 10-minute city ambitions could bear fruit one day.

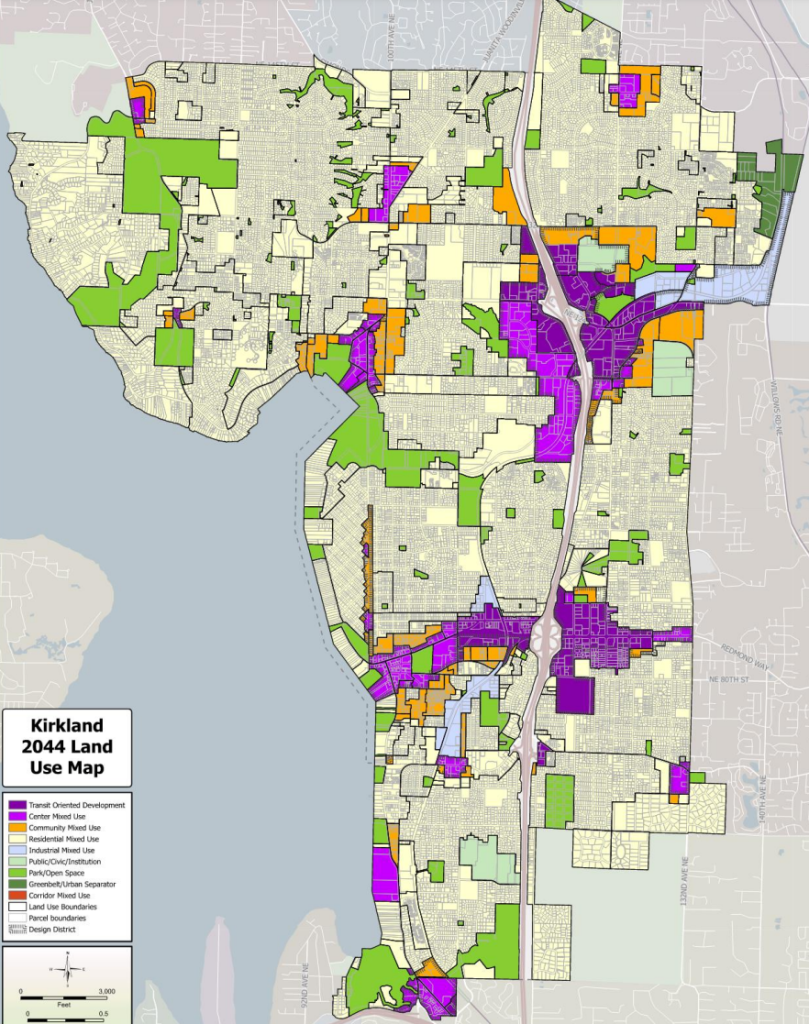

By a 5-2 vote, the Kirkland City Council last week approved a modest update to its 20-year growth plan, which doesn’t rock the boat too much, but could lead the city in the direction of creating more vibrant neighborhoods. The Kirkland 2044 plan (K2044, for short) mostly represents a continuation of the city’s current trajectory: focusing the most intense development in the areas of Kirkland close to current and future transit.

However, the plan also includes language pushing city leaders toward the work of creating more walkable districts near amenities like grocery stores and frequent transit. That language was the focus of a contentious debate within Kirkland, which has been rife with misinformation and acrimony.

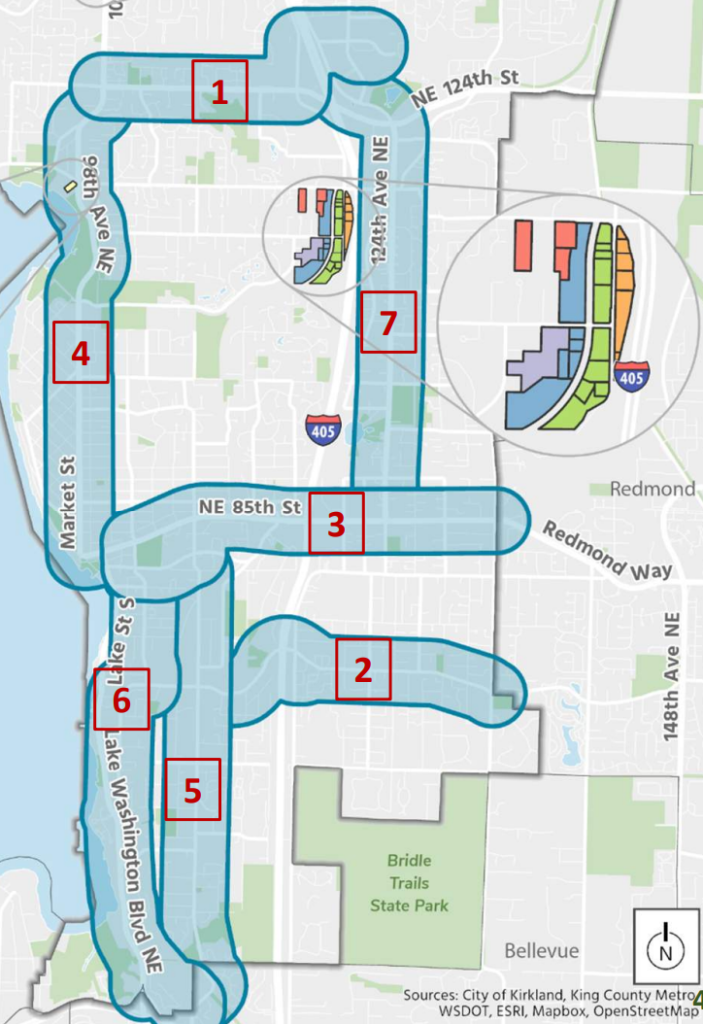

With no major zoning changes set to be put in motion as part of K2044, the city is poised to accommodate the lion’s share of its allotted growth target — at least 13,200 new housing units through 2044 — in the growing Totem Lake neighborhood and in its downtown, which includes the area around Sound Transit’s planned NE 85th Street Stride bus rapid transit (BRT) station.

Unlike many Puget Sound cities, which are scrambling to implement the new statewide minimum residential densities required by House Bill 1110, Kirkland already allowed a panoply of middle housing types across the city. In 2020, Kirkland legalized cottage housing, duplexes, triplexes, and accessory dwelling units. To comply with state law, the City will need only a package of tweaks set to be approved next year.

Earlier drafts of the K2044 plan set the city’s sights higher, seeking broader housing opportunities beyond the existing growth centers, in a city where the median house is currently listing at $1.3 million. Kirkland City staff and the Kirkland Planning Commission this past spring explored allowing increased housing density within a quarter mile of its most frequent buses, routes with service at least every 15 minutes throughout most of the day. A 2022 op-ed in The Urbanist advocated for doing just that around Route 255, one of Kirkland’s main workhorse buses.

The result of the City’s planning exercise was one policy added to the plan (LU-2.4) that would have recommended the city “create additional capacity for higher-intensity residential uses along identified frequent transit corridors citywide, and ensure development regulations enable multi-unit housing types.”

King County’s Affordable Housing Committee (AHC), as part of a first-ever review of local Comprehensive Plans to ensure they’re better aligned with the county’s overarching affordable housing policies, praised the transit corridor proposal in a letter approved late this summer. “Kirkland’s draft plan prioritizes transit-oriented development and lays a foundation or increasing densities sufficient to maximize transit investments in the city and increasing income-restricted housing within walking distance of frequent and high-capacity transit,” the committee wrote. “The AHC strongly supports the future addition of a Frequent Transit Corridor Overlay to the City’s land use strategy, which would add capacity for ‘higher-intensity residential uses’ along identified frequent transit corridors.”

But that transit corridors proposal, and the accompanying map that was used to study it, ignited a firestorm. A new group, Cherish Kirkland, formed to push back on the idea, and signs started popping up around the Market Street neighborhood alleging that “4 to 6 story housing” was being “proposed on this street.” Aside from the fact that the Comprehensive Plan doesn’t change zoning, the modelling used to study the transit corridor proposal looked at densities of 50 dwellings per acre, a density that would equate to more townhouse development but likely not four- to six-story buildings.

Even though City staff continued to emphasize that these concepts were preliminary, and that “[n]either the policy nor the map would commit Council to zoning transit corridors at any specific density,” per a staff report this summer, the city ended up on its back foot. A “reality check” website set up by the pro-housing advocacy group Livable Kirkland tried to dispel misinformation about the proposal, and some alternative language was floated, including a clarification that Kirkland would only look at the transit corridor proposal after the RapidRide K line and Sound Transit’s Stride BRT start operating. But in the end, the Kirkland Planning Commission voted to remove the LU 2.4 policy from the K2044 plan this fall in response to community concerns.

But rather than leave it at that, the Kirkland City Council acted on a primary criticism leveled at the transit corridors proposal — that allowing more housing near transit doesn’t translate to access to amenities. In November, a majority of councilmembers expressed interest in pursuing alternative language around increasing the number of 10-minute neighborhoods in Kirkland. That language ended up in the final plan, though the definition that was ultimately approved is cumbersome and doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue.

The concept of a 10-minute city or a 15-minute city or neighborhood has taken off in recent years as a way to explain all the elements needed for a complete neighborhood, in contrast with a car-dependent one. Downtown Kirkland, with plentiful transit, grocery stores, restaurants and health clinics all within a quick walk, bike, or roll of each other is a clear 10-minute neighborhood. Totem Lake is another example, as Kirkland has taken steps to add parks and open space to this growing commercial center built around a former shopping mall.

“A 10-minute neighborhood (10 minutes represents a typical one-half mile walk) is one in which residents have access to, and can safely travel short distances from home to destinations that meet their daily needs, using options other than motorized vehicles,” the plan states. “These communities comprise the following two important characteristics that can be used as a general indicator of access and safe active transportation options. A walkable community is one in which it is safe and easy to get to multiple destinations by walking, rolling, and bicycling to meet daily needs such as grocery stores, other retail uses, restaurants, schools, and parks. Walkability is enhanced by connected sidewalks, paths, and greenways, and convenient transit access.”

Implicit in 10-minute neighborhoods is increasing housing density and thus population so as to support the amenities, storefronts, and frequent transit going through the neighborhood, making the density of services viable over the long run. A neighborhood cafe with too few patrons won’t last long, after all. Kirkland’s definition does not touch on that housing aspect as squarely.

Kirkland’s Council had already been explicitly taking steps to create more 10- and 15-minute neighborhoods, moving forward with a plan to utilize a City-owned parcel near the Houghton neighborhood to create affordable housing and community amenities at the same time. With these revisions to the K2044 plan, they explicitly tied this work in with broader city direction, but the actual process of creating 10-minute neighborhoods around the city will be left to the future, and will almost certainly be contentious.

“What we have right now is a very moderate plan compared to what we started off with,” Adam Weinstein, Kirkland’s Planning and Building Director, told the City Council Tuesday as they considered final amendments. “When we started off, the comprehensive plan had capacity for something like 38,000 housing units, we’re now at 23,000 housing units, but it is a really strong plan for housing, both market-rate and affordable housing.”

But dropping the transit corridors proposal was not enough to get the entire Council on board. Voting against the K2044 plan last week were Councilmembers Jon Pascal and John Tymczyszyn, who argued that the city shouldn’t be spending its time looking at future areas where it might want to encourage growth and instead should be focused on existing growth areas. Ironically, these are the very areas where the vast majority of new housing is set to be built under the plan.

Kirkland, like many cities in the region, has sited the majority of the land zoned for multifamily housing near its major highway, I-405, even as research continues to show the negative health outcomes that come from living close to highways.

“I still see a comp plan that does not fully align with a policy of focusing growth in our urban growth centers and commercial areas,” Pascal said. “We have limited resources, and we can’t do it all everywhere. Diverting attention and resources away from our growth areas will only make it more difficult to accommodate the affordable housing we need.”

“We spent months of controversy about the transit corridor issue and all of the oxygen in the room had to be dedicated to that,” Tymczyszyn said. “Now we have a substitute to that, which is 10-minute neighborhoods, which is an ill-defined, incoherent, 177-word definition that nobody can explain to me. This is going to have to be litigated. There’s going to be tons of problems with the definition of 10-minute neighborhoods, and it is a replacement policy for transit corridors, and one that does not focus growth in any coherent fashion that I can figure out.”

In the face of the divided vote, the Council’s majority stool firmly behind the K2044 plan as navigating the often conflicting requests from community members while setting Kirkland up to be able to tackle its biggest challenges, including creating more housing and moving toward more scalable, sustainable transportation options.

“We’ve heard the stories of essential workers and unsustainable long commutes,” Deputy Mayor Jay Arnold said ahead of the final vote. “With Kirkland 2044 we’re focusing on increasing housing supply, housing affordability, leveraging existing and future transit investments and building middle housing. We’re tackling the problem so that there are opportunities to live in Kirkland at all ages and stages of life, where there are opportunities to live here, if you work here, where we continue to build a complete city with shops, restaurants, amenities, recreation and all your favorite places. That’s what we’ll be achieving in Kirkland in 2044 and this plan is a huge step to get there.”

Kelli Curtis, who was elected Kirkland’s Mayor earlier this year by her council colleagues following a 2023 re-election campaign where the issue of housing was front-and-center, painted the final plan as a direct representation of community priorities. During the same election, Councilmember Amy Falcone was also re-elected, in a fairly strong endorsement of the council majority’s direction.

“You asked us to focus the housing element on the urban growth centers and the neighborhood centers,” Curtis said. “You told us that you cared about the missing middle housing policies, that we focus the growth at Totem Lake, that the rezone at 85th station area plan is the direction that you want us to go. You asked us to tie growth in with services and transit and park space and more. And we’ve been clear that we will continue to focus on sustainability, expanding parks and open space, the things that make Kirkland special. We have focused in this plan on smart growth and building a livable community.”

While the debate over the Comprehensive Plan may be over, the need to navigate between voices advocating for the status quo and a clear need to accommodate change within a rapidly growing region is only likely to intensify. In the end, the K2044 plan may only prove to be a warm up for that larger conversation.

“We’re facing an affordable housing crisis, and yes, as was mentioned earlier, we have state requirements that we have to comply with, but in true Kirkland fashion, we’re rising to the challenge and really trying to address the issue at hand, and not just the minimum of what’s legally required of us,” Falcone said. “As a mom of three school aged kids, I just shudder to think of how they will ever afford to live in or near Kirkland if we don’t take bold action, as we’re doing in our Comprehensive Plan.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.