Sound Transit’s governance structure and limited organizational powers cause project delay, inflated costs, and lower quality service. The West Seattle Link and Ballard Link extensions are the newest chapters in this long history. Sound Transit 3’s ambitious vision for the region is threatened by the failure to address flaws exposed by Sound Transit 2’s and Sound Move’s (Sound Transit 1) challenges.

The State must act to streamline Sound Transit’s governance, eliminate jurisdictional extortion, and empower Sound Transit to execute the vision for transit approved by voters.

Based on past project challenges and the experiences of agencies that have successfully reformed project delivery the state legislature must:

- Audit Sound Transit’s governance, decision-making, and powers in comparison with national and global leader’s in transit delivery,

- Identify powers to facilitate delivery for Sound Transit and opportunities to partner with Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) to leverage their capabilities to expedite project delivery,

- Establish a Blue-Ribbon Commission to identify how the State and local governments can effectively deliver promised infrastructure projects faster, cheaper, and better by reviewing global best practices in infrastructure delivery.

To write a letter supporting this effort click here or visit transportationreform.org.

Sound Transit Board: Misaligned Goals, No Accountability

Seventeen of the 18 members of the Sound Transit Board of Directors are elected officials, the 18th member is the State Secretary of Transportation. The county executives of King, Pierce, and Snohomish counties are automatically board members and rotate chair duties. The executives also appoint elected officials to their respective county delegation seats, which are weighted by population in the taxing district. Meanwhile, voters approve funding regionally across Snohomish, King, and Pierce Counties.

Board members are among the host of decision-makers who are accountable politically to their jurisdiction and its parochial local concerns, except they are also expected to shepherd transit projects of regional interest. This creates a clear conflict of interest. Board members are tasked with making decisions on projects that impact their city or area of representation without exposure to the costs of those decisions since they are shouldered by the region. Unfortunately, board members often wield their powers as local officials to the detriment of Sound Transit.

Keeping Sound Transit weak empowers local jurisdictions to extort resources via permitting and regulatory powers. Sound Transit does not even have the power to enforce a consistent fire standard across jurisdictions. Instead, each jurisdiction interprets the fire code independently. Bellevue, despite having no prior experience with transit tunnels, forced a tunnel redesign due to a contrary interpretation of the national fire code.

The current structure incentivizes delay because each day of delay means more tax is collected and prior debt retired – increasing the capacity to underwrite more expensive projects in many of their own jurisdictions. Meanwhile, the threat of delay to Sound Transit increases the willingness of Sound Transit to give into opponent demands to keep projects moving.

Sound Transit’s governance structure and limited powers results in five major limitations:

- Local jurisdictions can impede or veto project elements without consequence.

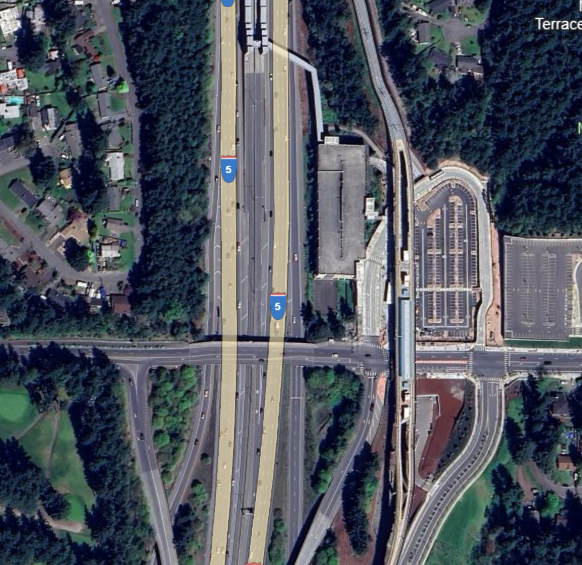

- Short-term inconvenience is prioritized over multi-generational value and what voters approved (Interstate 5 Alignments, Bellevue Alignment, Chinatown/International District Hub).

- Sound Transit alone bears the cost of process delays.

- Sound Transit must fund projects before detailed planning is complete, but has limited control over project final design elements, such as adding a tunnel in West Seattle.

- Board members are not accountable for their decisions and many their responsibilities as board members and local electeds are in direct conflict

These shortcomings are evident in challenges experienced in each voter approved transit package.

Overview of Voter Approved Sound Transit Packages:

- Sound Moves (1996): A mix of express buses, commuter rail, and 23 miles of light rail. One-third of original light rail was cut due to budgetary constraints. Total Cost: $3.9 billion

- Sound Transit 2 (2008): 36 miles of light rail, a 30% boost to Sounder commuter rail service, and additional express bus service. Total Cost: $18 billion

- Sound Transit 3 (2016): 62 miles of additional light rail service, 45 miles of bus rapid transit, and a Sounder extension to DuPont. Total Cost: $54 billion

Sound Moves – A Missed Opportunity in Tukwila (1996-2002)

Sound Transit and the City of Tukwila engaged in a contentious multi-year negotiation for the routing of the initial light rail segment from Downtown to SeaTac Airport. Despite a route serving a station at South 144th via Tukwila International Boulevard being cheaper, faster, and approved by voters, Tukwila successfully lobbied to reroute the line to Interstate 5. The reason being to prevent rail “destroying” the area’s economic development. The claim lacks credibility given the only businesses in the vicinity were a Jack in the Box drive-thru, a gas station, and small business surrounded by empty parking lots. The City concluded preserving the existing use provided greater value than a multi-billion dollar direct connection to Downtown Seattle and SeaTac Airport.

The experience with Tukwila previewed a recurring pattern for light-rail projects regionwide, Sound Transit negotiating away value to appease local jurisdictions or politicians. The fundamental issue is: Voter’s approve funds for a transit vision whose implementation depends on the approvals of every jurisdiction the project crosses. However, these jurisdictions are not exposed to the cost or delay impacts of their decisions and have leverage over Sound Transit.

Egregiously, after negotiating a memorandum of agreement for a I-5 route, the City of Tukwila attempted to torpedo Federal Transit Administration (FTA) funding when they surprisingly rejected the memorandum. They hoped to strong arm Sound Transit into adopting an unfunded route serving Southcenter by imperiling the entire project.

However, the FTA regional administrator found the agreement was unnecessary since light rail is an “essential public facility” under the Growth Management Act. This designation meant Tukwila could not “preclude the light-rail alignment selected by Sound Transit.” Sound Transit also threatened to pursue permits under light rail’s special status. While Sound Transit eventually reached the point of threatening permitting by force, these powers are rarely employed due to the time and cost of using them. Unfortunately, no reforms were implemented following ST1. Appeasing stakeholders by compromising projects versus fighting for the best project remained the most effective means to build transit.

ST2: Missed SR 99 Opportunity and Process Purgatory

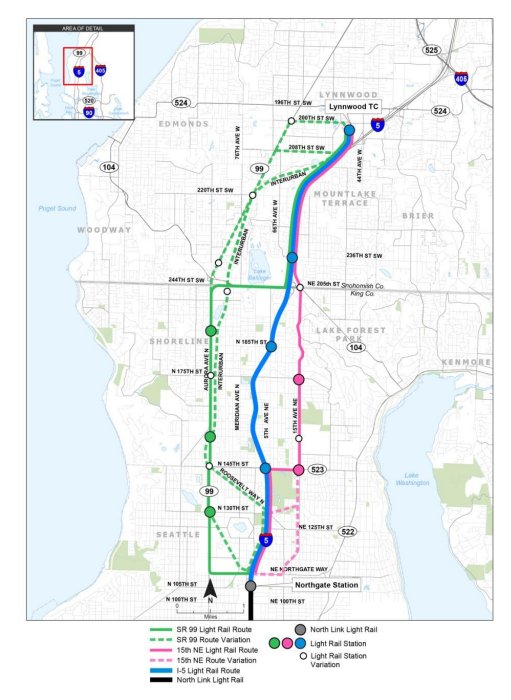

Sound Transit again deferred to local concerns when selecting the route to Lynnwood. Instead of following the more populous and developable SR-99 corridor, Lynnwood fought for an I-5 alignment to avoid construction disruptions. Instead of catalyzing regeneration and growth along the 99 corridor as the region emerged from the Great Recession and entered a tech-fueled boom, the corridor was little changed more than a decade later. While significant redevelopment has occurred where stations were constructed, the capacity for housing and opportunity for future infill stations is diminished due to I-5’s massive size.

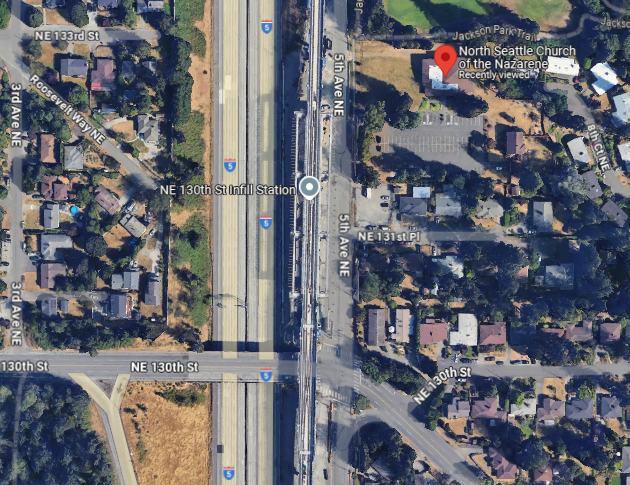

Change is slow to come to the SR 99 corridor absent a light rail catalyst. The following images show the three station locations identified on Aurora Avenue (SR 99) in 2011, the year the decision to route along on I-5 was made, versus today.

Aurora Avenue and 130th Street

Aurora Avenue and Linden Avenue

Echo Lake Station

Elected officials had a generational opportunity to remake the crash-prone and struggling 99 corridor around transit. Instead of seizing the moment, they prioritized short-term convenience over long-term benefits. Worst of all, by placing the stations immediately next to I-5, the land most suited for dense, tax-generating, and ridership-building transit-oriented development is consumed by roadway. The I-5 alignment has much less redevelopment potential and an undesirable environment adjacent to an interstate.

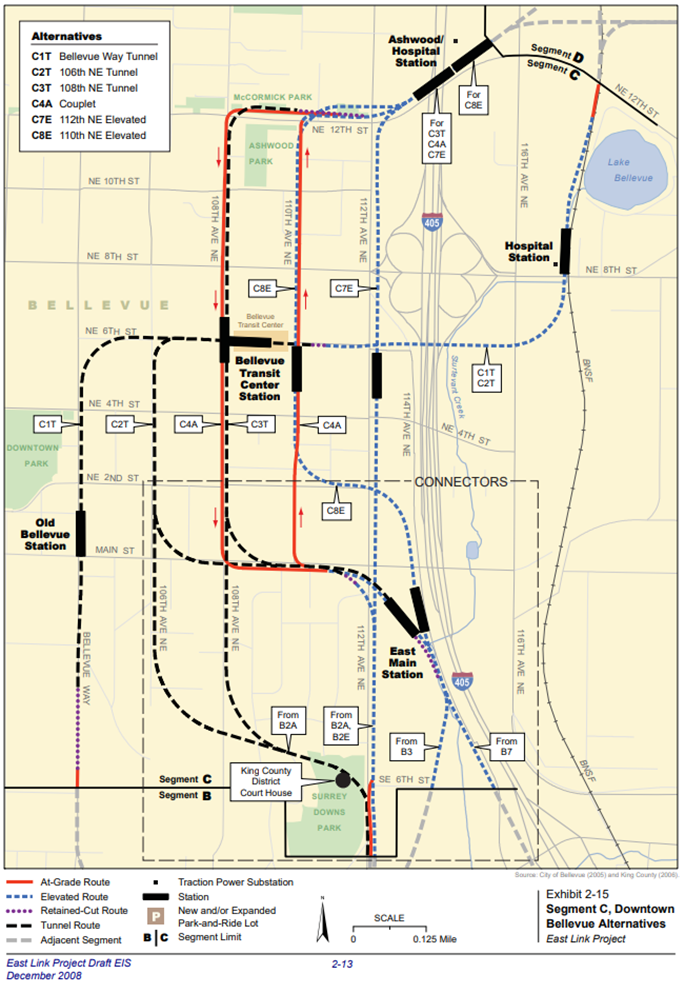

While Lynnwood Link found a lower value, politically viable route, East Link spiraled into a three-year delay beset by lawsuits and a multi-year political battle between Kemper Development and Seattle-based development firm Wright Runstad. Sound Transit examined 36 alternatives, eventually reaching a compromise route featuring a tunnel but skipped the downtown core allowed the project to proceed.

The fact the value of a project approved by voters at-large hinged on a protracted local fight highlights the disconnect between a regional vision affirmed repeatedly at the ballot box and the reality that its implementation depends on local electeds whose motivations are completely removed from that vision.

Sound Transit 3 – History Repeats Itself, Again, and Again

Given the challenges experienced in Sound Moves and Sound Transit 2 selecting routes and negotiating with jurisdictions and stakeholders, Sound Transit 3’s West Seattle to Ballard Link’s challenges were foreseeable. Sound Transit even tried to prevent a repeat by spending $33 million on early outreach and engagement to identify a preferred alternative to West Seattle from 2017-2019. However, this early scoping work was thrown out due to opposition to elevated alternatives.

When the elevated option failed to secure support in 2019, identifying funding for a tunnel was paramount, with Councilmember Herbold stating: “We’re going to need third party, fourth party, and fifth party funding.” In lieu of new funding, project delays allowed for bonding capacity to increase, making financing for a tunnel that adds $600-850 million in cost compared to an elevated option viable.

Ironically, West Seattle elected officials killed a cheaper elevated option that would likely open years earlier, which West Seattle voters had approved five times over. Over 60% voted for an elevated option in Sound Transit 3 and an elevated monorail four times.

While delaying projects increases available financing, delay is also the single largest source of project cost increases. The original estimated cost for the West Seattle Link Extension in 2014 was $1.4-1.5 billion ($340-360 million per mile). Since approvals, costs have more than quadrupled to $6.7-7.1 billion ($1.63-1.73 billion per mile). The National Highway Construction Cost Index, a federally maintained database on transportation construction costs nationally, suggests that 55% of the cost increase are attributable to construction cost increases while 45% could be attributable to routing and scope changes from the original proposed alignment.

Over the last 10 years, construction costs have increased by a factor of 2.56 with 58% of that increase occurring in the last three years due to a Covid-era spike in costs. While Sound Transit cannot control broader economic forces, prolonged processes expose projects to cost and delay risk, due to increased likelihood of experiencing an external ‘shock.’

Sound Transit’s prolonged processes are also attributable to pairing planning and construction. As Eric Goldwyn, member of Sound Transit’s Technical Advisory Group and leader of New York University’s Transit Costs Project recently asked: “Does anyone know why projects/programs like Sound Transit (2/3), California High Speed Rail, etc. go to the ballot with such a small amount of design work completed? […] It seems like a classic example of putting the cart before the horse.”

The region approves funding to build projects based on cost estimates for projects that decision-makers have not agreed to since planning has not concluded, while these decision-makers are accountable to their own constituencies. Therefore their incentive is to extract benefits for their interests because the costs of their demands are diffused regionwide, while the benefits accrue directly to their constituents. This invites abuse and prolonged negotiations since Sound Transit does not have the power to efficiently tell decision-makers ‘no.

Simultaneously, Sound Transit’s capacity to finance the decision-makers ask increases with time as bonding capacity increases via retiring debt or delaying (‘re-aligning’) later projects. Sound Transit’s planning timelines, already long, are getting worse (Vancouver’s SkyTrain included for reference, see table below).

| Project | Early Scoping | Final Environmental Impact Statement | Duration |

| Northgate Link | October 2001 | April 2006 | 4 Years 6 Months |

| East Link | September 2006 | July 2011 | 4 Years 10 Months |

| Lynnwood Link | October 2010 | July 2015 | 4 Years 9 Months |

| Federal Way Link | October 2012 | November 2016 | 4 Years 1 Month |

| West Seattle Link | February 2018 | September 2024 | 6 Years 7 Months |

| Ballard Link | February 2018 | TBD | 7 Years + |

| SkyTrain Surrey/Langley | 2019 – 2020 | 1 Year 6 Months | |

Redmond – A Case Study in Planning and Leadership

Redmond provides an example of what project planning and development should look like. Originally slated to receive transit in 2032-2036, service is expected to begin in 2025 due to the city’s supportive approach under the leadership of Mayors Rosemarie Ives and John Marchione.

Redmond is unique, featuring the largest daytime population increase nationally. Leaders foresaw that accommodating future employment growth required providing alternatives to driving and increasing housing options within the city. Redmond funded their own planning studies beginning in 2006. This allowed planning and construction to proceed separately. Critically, in contrast to other extensions, Redmond identified preferred track alignments prior to entering environmental review and preserved the right of way to prevent future conflicts.

These efforts resulted in an official record of decision under East Link’s environment impact statement during ST2, allowing engineering and construction to commence with ST3’s passing in 2016. The City also declared transit as ‘use by right,’ meaning permits are proactively approved, in contrast to other municipalities that leverage permit approvals for betterments. Redmond’s experience should be the norm, not the exception. State-led reform can ensure this is the case via planning and permitting reforms.

Redmond brought light rail to town a decade earlier than planned and leveraged it to create a vibrant town center. (Source: Google Earth 2006 vs. 2024)

The Path Forward on Reform is Known

Montreal’s Réseau Express Métropolitain (REM), approved in 2015, provides a stark contrast of what an outcome-based structure can achieve. A year ago, the first phase of an eventual 41-mile, 21-station REM line opened, at a cost of $141 million per mile. It also features full automation with trains arriving every two minutes at peak hours.

In contrast, Ballard/West Seattle, approved in 2016, was estimated at an already high by international standards $340-360 million per mile with trains arriving every six minutes during peak hours. Since approvals, costs have exploded to $1.63-1.73 billion per mile. More than a quadrupling of costs yet years from groundbreaking (values unadjusted for inflation, projects experienced similar price environments since started one year apart).

Montreal went from concept to opening in less time than Sound Transit chooses a route. Montreal delivered three times the service in half the time and a tenth the cost. REM’s success is no accident. After witnessing prior project difficulties, provincial legislators paired its authorization with governance, design, permitting, and procurement reform.

Sound Transit took its first steps to improving delivery by implementing the Technical Advisory Group’s recommendations. However, these reforms cannot remedy the five identified shortcomings. These require action by the state legislature. Minnesota provides an example to follow.

When the Southwest Light Rail Line went $1.5 billion over budget and nine years behind schedule, the Minnesota State Legislature audited it and implemented reform recommendations in their next transportation bill.

Based on Minnesota’s experience and examples globally of successful reform efforts, Sound Transit’s path forward starts with the legislature. Three actions must occur in this session’s transportation bill:

- A legislative inquiry and audit investigating Sound Transit’s planning and decision-making processes to identify how its governance structure contributes to poor outcomes. The legislature should look to the experience of international peers, such as Montreal, that consistently deliver transit infrastructure at lower costs.

- A review of Sound Transit’s powers and opportunities to partner with the Washington State Department of Transportation to leverage their authority and capabilities. Critical focus must be placed on eliminating redundant regulations and excessive process, examples include: auto-permitting, betterment policies, and design standards (i.e. fire) more broadly.

- Finally, given WSDOT faces its own delivery issues, a review of infrastructure delivery is necessary. The state legislature must tap leading experts and establish a blue-ribbon commission focused on how to deliver projects based on a global perspective. The United Kingdom’s recently completed Cost Drivers of Major Infrastructure Projects report provides a strong model.

Sound Transit’s cost, delay, and project quality shortcoming are not sustainable. The failings of the current process are evidenced by decades of increasingly poor outcomes. Unless action is taken, the region will continue to squander opportunities to make progress on climate, economic, health, and social objectives. State officials must act to fix this broken system.

Please sign our LETTER.

Transportation Reform is dedicated to reforming processes that cause expensive, delayed, and inadequate transportation projects. If you are interested in joining our coalition, please contact trevor@transportationreform.org.

Trevor Reed is a transportation planner who lives in Mercer Island and represents the East-King Subarea on the Sound Transit Community Oversight Panel. He completed his Master's degree at the Bartlett School of Planning focusing on large project delivery and worked as a researcher at the Omega Center: Center for Mega Infrastructure and Development. Currently, Trevor works in transportation data analytics focusing on road safety and network efficiency. His work concerning the impacts of traffic congestion on cities has appeared nationally in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and PBS's Nightly Business Report. He co-founded the advocacy group Transportation Reform.