In advance of the 2025 legislative session, Washington’s outgoing transportation secretary Roger Millar is laying out the cost of continuing the status quo approach to statewide transportation funding. The warning comes just as lawmakers prepare to return to Olympia to craft a two-year budget, against a backdrop of declining transportation revenue, increased project costs, and major bills for current projects coming due.

Millar is set to leave the helm at the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) in mid-January, following Governor-elect Bob Ferguson’s announcement that he’ll seek new leadership at the state’s third largest agency. He departs after eight years of promoting a fix-it-first, multimodal approach.

Ultimately, the head of WSDOT implements the transportation budgets proposed by the governor and approved by the state legislature –which generally emphasize highway expansion — but Millar made a point during his tenure to urge lawmakers to think long-term and emphasize safety when choosing investments. He’s also urged a focus on land use to solve problems that have historically been thought of as transportation issues, such as by reducing sprawl and encouraging dense transit-oriented housing.

The WSDOT secretary also sits on the Puget Sound Regional Council’s (PSRC’s) Executive Board, and last week’s meeting was the final one Millar was scheduled to attend. On the agenda was the four-county regional planning body’s official 2025 legislative priorities, which commit PSRC to advocating for “exploring stable new revenue sources to address declines in existing revenue, ensure projects of regional significance are built and fully fund maintenance and preservation.”

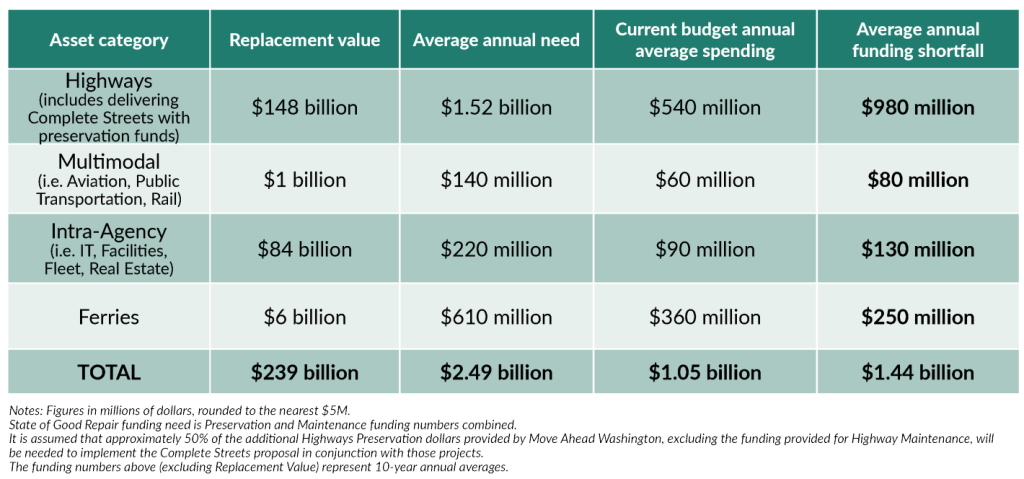

While Millar abstained from the vote approving the agenda due to his role, he noted that the list of priorities didn’t include any mention of which items should be put ahead of others given limited resources. With a $3.1 billion budget gap in the state transportation budget projected through 2031, lawmakers have their work cut out for them — and are already starting out behind. The current gap between what the state spends and what it would need to spend to keep its transportation system in a state of good repair stands at $1.44 billion per year, with $980 million of that needed for the existing state highway system.

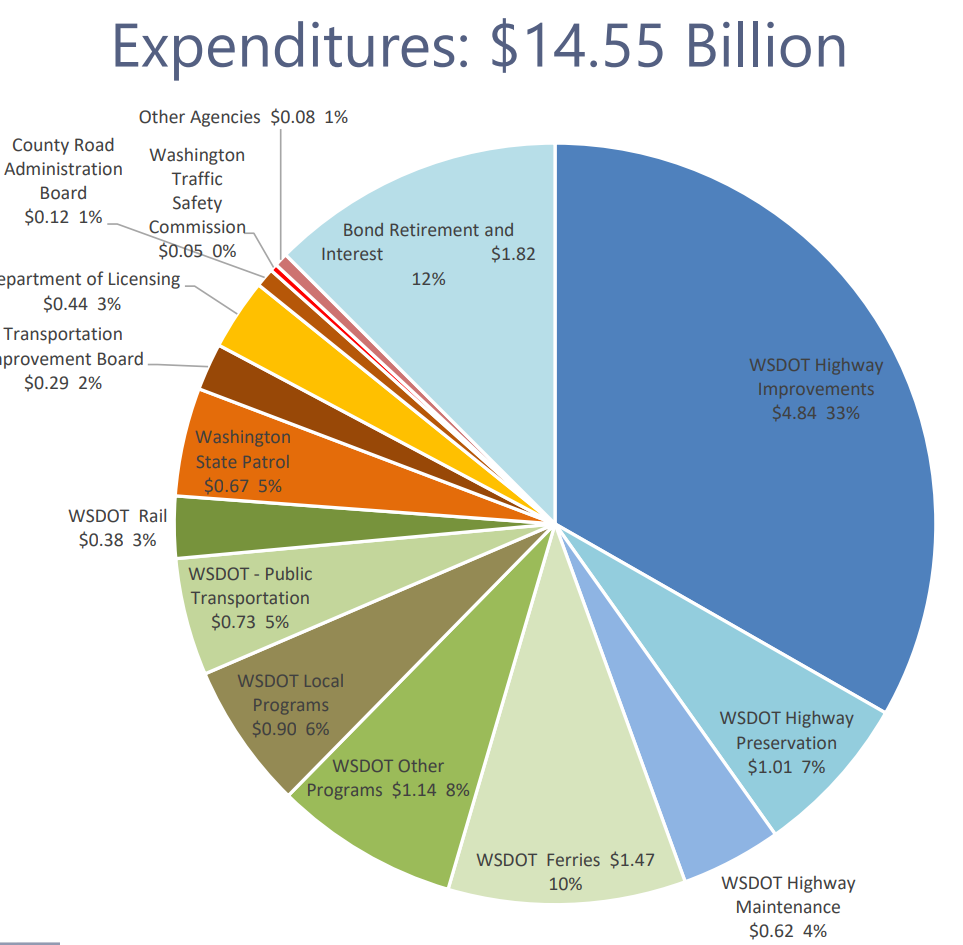

A full third of the $14.5 billion supplemental transportation budget approved in 2024 goes toward highway “improvements” — capacity expansion projects and court-mandated fish barrier removal projects, along with a small number of safety improvement projects — compared to 11% for highway maintenance and preservation. Those highway expansion projects include the North Spokane Corridor, the Puget Sound Gateway, 520 Bridge Replacement, I-405 widening projects, and the I-5 Interstate Bridge Replacement in Clark County — the most expensive highway project in state history.

With lawmakers having to go back to the drawing board in light of reduced revenue, Millar pushed PSRC, clearly a stand-in for policymakers more broadly, to think about prioritization.

“There are really two basic ways to tackle this, one is to find the funding for the projects, and then if there’s anything left, put that into preservation and to maintenance and to safety. That has, I think, been the tradition for the last 25 years,” Millar said. “Another way to do it would be to fully fund preservation and maintenance and safety and see what’s left and apply that money to the projects as appropriate.”

He also suggested that lawmakers don’t always align investments with their espoused values and priorities.

“Everybody puts safety first, but it’s a very, very, very small part of our five and a half billion dollar figure [annual] budget,” Millar continued. “And then everybody puts preservation and maintenance first on their list, and we’re funded at less than 40% of what’s needed to maintain the system we have today in a state of good repair.”

Preservation funding now comes paired with mandatory upgrades to pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure and speed control thanks to Washington’s Complete Streets mandate, which Millar backed.

Millar has also advocated a focus on safety upgrades by tackling the 1,100 miles of state highways that run through population centers. Those roadways, which include streets like SR 99 through King and Snohomish County and SR 7 through Pierce County, are some of the most dangerous roadways in the state for all users. Earlier this year, WSDOT set a baseline of needed funding at $150 million annually to tackle those roadways, a program that would be the first of its kind.

“In the last 25 years, our economy has grown 40%. Our population has grown 35%. We have invested, with the Nickel and the TPA and Connecting Washington and Move Ahead Washington [transportation packages], billions and billions and billions of dollars on expanding our transportation system,” Millar said. “We have expanded our transportation system 2.5% in the last 25 years, which indicates to me that there maybe isn’t a connection between economic prosperity and more highways, but I do believe there is a connection between economic prosperity and having the facilities that we run our economy on be reliable.”

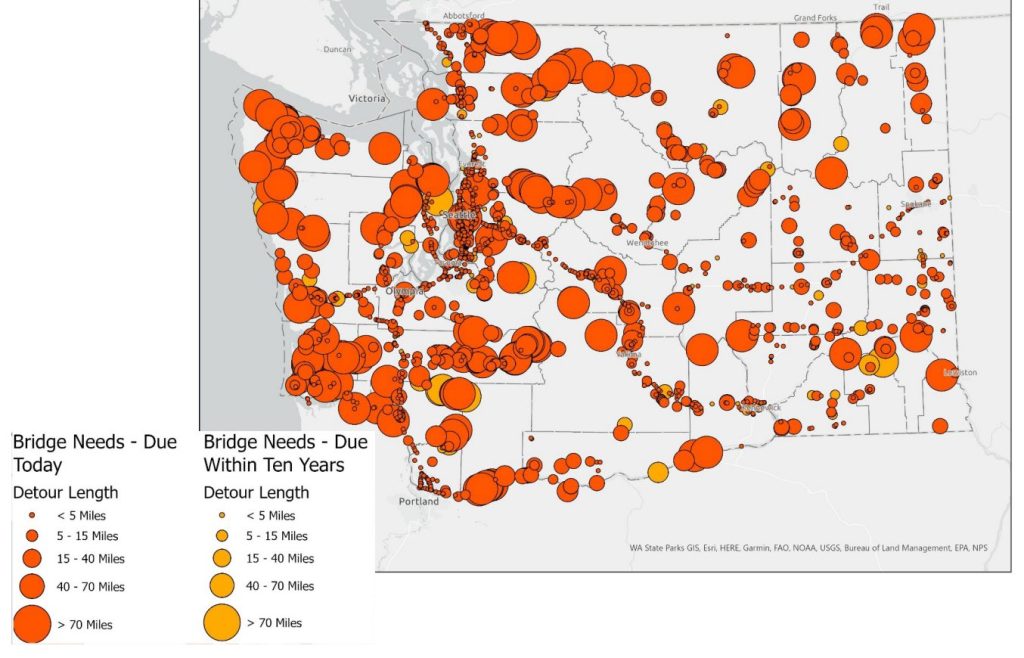

A WSDOT presentation to the state senate’s transportation committee earlier this year broke down the dire state of the state highway system, describing the network as in the “early stages of failure.” With limited funds, the agency has been forced to prioritize emergency repairs that are starting to pop up with increasing regularity. As of this summer, 100% of the preservation dollars allocated by the legislature through mid-2025 were already accounted for, along with 25% of the funds expected through mid-2027.

A map shown to lawmakers showing only state-owned bridges illuminates the state of the problem: facilities in every corner of the state have maintenance needs that are due today. If those investments aren’t made, they become even more costly, even as emergency closures become more impactful to the state transportation network and can’t be scheduled at more optimal times.

The lack of maintenance funding is impacting state assets way beyond the highways and bridges themselves, with a report delivered to the legislature this fall detailing the state of the agency’s buildings, which number nearly 1,000 statewide. “A majority of WSDOT facilities are in poor or critical condition; walls, roofs, windows, doors, heating, cooling, electrical, plumbing and structural element are all at risk of failing or in need of repair,” the report noted.

Millar did not sugar-coat the impact of continuing to neglect maintenance and preservation funding in favor of getting highway expansion projects across the finish line.

“I am concerned, absent investment in maintenance and preservation and safety and operations, our system will not be reliable,” Millar said. “All I need to do is have one bridge on I-90 between Idaho and Seattle become load-restricted, and every truck on that highway will no longer be able to be loaded 80,000 pounds. The same thing on I-5, and that is coming.”

With a severe budget crisis looming, something has to give — and that something is usually maintenance, safety, and active transportation improvements. Continued neglect would leave the state’s roads to crumble and the traffic safety crisis unabated. Or legislators can flip the script, reprioritize, and avoid the type of failure. The choice is theirs.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.