Days after finalizing a 2025 budget, King County Executive Dow Constantine and the King County Council met with state lawmakers this week, advocating for legislative fixes to some of the county’s most structural financial issues. While the one-year budget that was ultimately adopted in late November avoided major cuts to programs and services, King County faces a significant fiscal cliff for 2026 and 2027, with a projected deficit of $150 million over two years.

Monday’s annual meeting with King County’s legislative delegation, lawmakers from 17 districts from Woodinville to Federal Way, was a formal opportunity to present the County’s legislative priorities for the 2025 session, which starts January 13. That 105-day session offers one final chance to provide Washington’s largest county with another lever to pull in order to preserve essential services, heading into budget season next year. Removal of the 1% annual cap on the property tax levy increase is the top of the County’s list.

“Unlike cities of the state, we do not have the authority to implement a B&O tax, utility tax, a capital gains tax, a payroll tax, like the one in Seattle — we are primarily reliant on property tax, and these limitations hamper our ability to respond to the evolving needs of our residents,” Constantine told lawmakers. “Unincorporated King County all by itself, even though it’s barely more than a tenth of the county, is still bigger than Spokane. It’s smaller than Seattle, but bigger than Spokane. So we have a lot of local government duties that we need to fund, that we can’t fund.”

The county’s 2026 budget cliff doesn’t impact agencies with dedicated funding streams, including King County Metro, though issues at Metro will require attention in future years as federal funds are fully exhausted and Metro’s financial reserves start to dwindle.

Property taxes are the primary way the County funds its programs. Tim Eyman-backed Initiative 747, which passed in 2001, limited annual growth to 1%. As a result, property tax revenue is not able to keep pace as expenses increase with inflation and population growth, and the problem is exacerbated in times of high inflation like the region has recently faced.

The court struck down Initiative 747 as unconstitutional in 2006 and the state Supreme Court affirmed the decision in 2007, but Democratic Governor Christine Gregoire, House Speaker Frank Chopp, and Senate Majority Leader Lisa Brown led the charge to pass it at the state legislature level in a one-day special session, putting the cap back into force that same year.

According to the County, if that 1% cap had never been put in place and the County’s General Fund had been able to keep up with both types of growth, collections would have been $819 million last year — a $400 million difference from what was actually brought in.

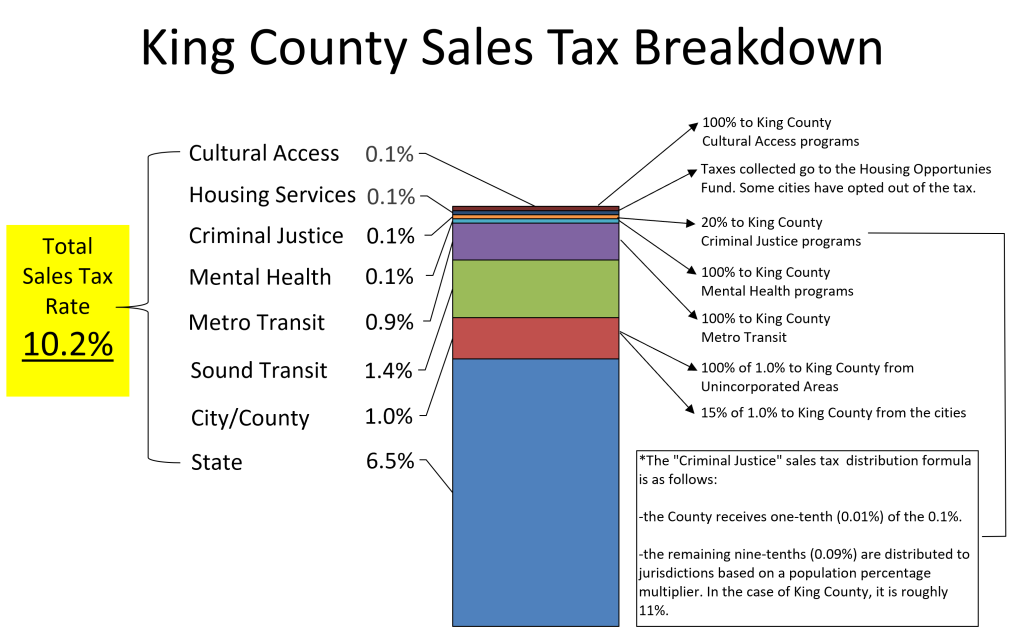

Sales tax, while high at 10.2% in King County, mostly goes to the state, local cities and towns, Sound Transit, and Metro.

A 2024 bill to allow localities to increase the 1% cap to 3%, proposed by Senator Jamie Pedersen (D-43, Seattle), was approved by the Senate’s Ways and Means Committee, but did not make it to the floor. With one additional seat for Democrats and significant turnover in the Senate in the 2024 election, the bill’s chances are stronger next year. But even if a new 3% cap is authorized, it won’t be a panacea for King County, with just $25 million expected in additional revenue over two years.

The 2025 budget the County ultimately approved did make some cuts to prepare for the anticipated shortfall next year, mainly to vacant positions. But the County isn’t expecting to get through next year’s budget without significant cuts across all of the departments that depend on the General Fund. During deliberations of amendments in November, County Budget Director Dwight Dively broke down what that might look like.

“Some spending we have almost no discretion over, we don’t really have a choice to cut it in any meaningful way,” Dively told the Council. “Many of our agencies will be looking at budget reductions in excess of 10% unless there is more revenue, either from the legislature or from a ballot measure if one were proposed and the voters approved it. I think in some cases, agencies would be looking at 15%, and then there are some programs that are entirely discretionary, that are ultimately up to the decisions of the Executive and the Council, I think we could very easily see all of the General Fund support for such programs eliminated.”

King County isn’t alone in facing a significant budgetary crisis. Other counties and cities do, too. And the state has its own fiscal crisis looming.

“Many of the challenges, you won’t be surprised to know, that you’re facing, we’re facing only amplified,” Senator Pedersen told attendees. “The budget shortfall in the operating budget is likely approaching $14 billion over the next four years. Our budget shortfall on the transportation side is roughly $8 billion over the next 10 years.”

Last month, Pedersen went from Senate Floor Leader to Majority Leader, and will play a central role in finding a path forward.

The most common tool to get around the 1% cap is to send a levy to the voters — and King County is already planning three separate ballot measures in 2025: renewing the Automated Fingerprint Identification System levy, the Emergency Medical Services/Medic One levy, and the County’s Parks levy.

“Parks used to be in the general fund, and now it’s not. We don’t have any more spots on the ballot to go out and ask for money to do things that used to be in the general fund,” Constantine said. “We need additional tools, and we need tools that are sustainable and flexible and progressive.”

Earlier this year, the legislature did give King County one tool to avoid potentially devastating cuts at Harborview, the regional medical center that the County operates jointly with UW Medicine. House Bill 2348 allowed the county to levy an additional property tax to fund Harborview, and the final 2025 budget is set to raise $87 million using this funding source. Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda, chair of the County Board of Health, thanked lawmakers for this move, but noted an equally critical need to find a sustainable funding source for the county’s public health clinics.

“As we’ve been talking about Harborview tax, we’ve also been talking about the need for investment across the continuum of care, and recognizing that as we stabilize public health services, fewer people may end up at Harborview more people may have their services treated in a preventable way,” Mosqueda said, noting that the County needs to find a way to fund an additional $23 million for those clinics sometime within the next three years. “We have a temporary solution that helps provide additional support […] but this is a very short term window.”

King County is also asking for state support in standing up its five Crisis Care Centers, funded via a special levy in early 2023. While the funding plan for standing up these centers included construction and operating costs, it banked on receiving start-up costs from the state. But those funds are only available for centers that have been operating for at least six months, Councilmember Sara Perry told lawmakers, and aren’t available retroactively. The first center opened this past spring in Kirkland, with the others planned for North, South, and Central King County and another dedicated solely for youth services.

“Because the state waits for those six months and doesn’t fund retroactively for those startup costs, we’ve lost $14 million with Connections at Kirkland already, and so what we’re asking is that you work with us, knowing that this is based on a model that we know about already that works,” Perry said.

In the end, most of these fixes are Band-Aids, with decades of these structural constraints on county-level funding not something that can easily be dug out of. With long-deferred maintenance needs impacting everything from roads to buildings, King County has been making due with less, but ultimately those costs accumulate as facilities start to fail.

“In the General Fund, we should be spending something like $100 million per year on major maintenance of our facilities,” Dively said. “We spend less than a quarter of that. So we’re always making very difficult choices about what to fund and what not to fund.”

No fixes that are implemented in the 2025 legislative session will be a silver bullet for King County’s woes, but they have the potential to get things onto the right track, and provide a way for services in one of the fastest-growing counties in the country to start to keep up with demand.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.