Council mostly went with Harrell’s budget plan, growing police spending by 16% while cutting deeply elsewhere.

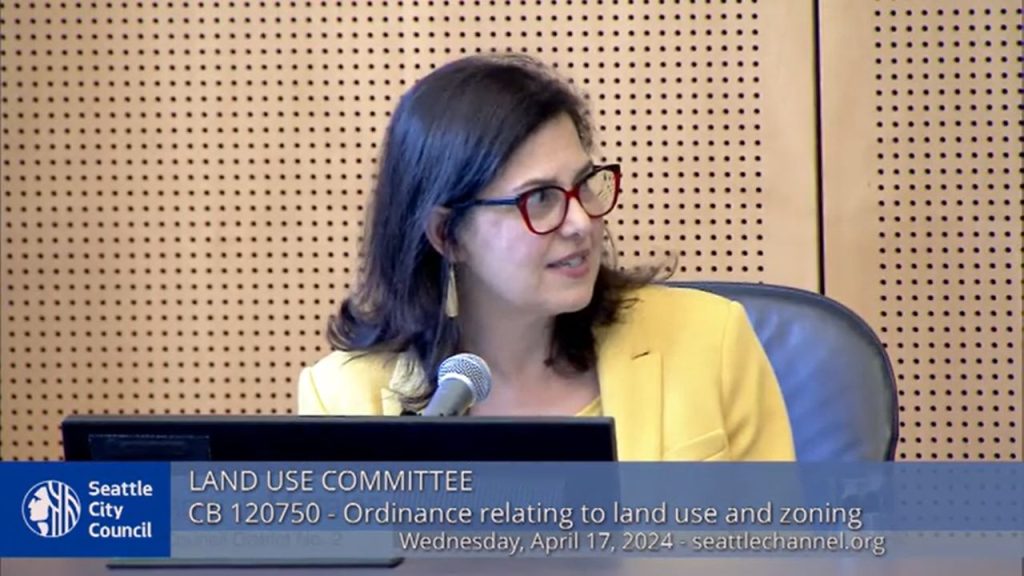

On Thursday the new centrist-led Seattle City Council passed their first city budget as a cohort, with Councilmember Tammy Morales casting the sole opposing vote. The council’s 8-1 vote greenlit the mayor’s plan to slash investments in affordable housing and social services and trim 48 staff positions in order to boost police spending by 16% and close a large deficit without raising new taxes.

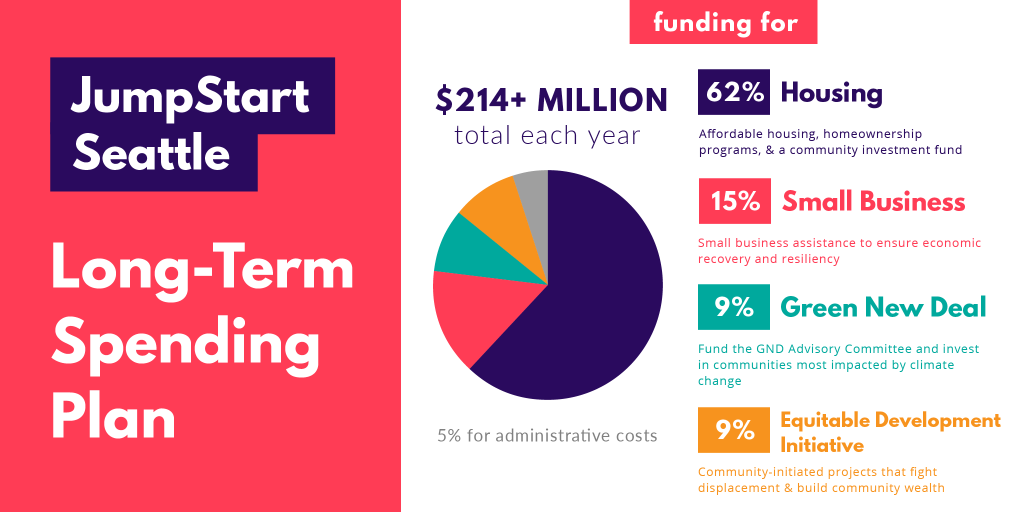

This year, Mayor Bruce Harrell’s proposed budget transferred a record-breaking $287 million from the JumpStart payroll revenue tax into the general fund to both plug a $250-million-plus budget deficit and fund $100 million in new priorities. Rather than clawback the transfer, Council blew an even bigger hole in the JumpStart fund, which is largely dedicated to investing in affordable housing.

After an unfavorable revenue estimate in October and the addition of Council’s earmarked spending priorities, the transfer from JumpStart grew even larger in Budget Chair Dan Strauss’s balancing package, coming out to $304.6 million in 2025. Nonetheless, Strauss spoke proudly about the council’s work “to be able to address one of the biggest budget deficits in recent memory while safeguarding the vast majority of public-facing services that our community depends on.”

Morales saw the issue differently. She argued against diverting affordable housing funds and permanently removing the guardrails around JumpStart spending categories, which could turn it into a perpetual slush fund for future mayors and councils.

“Despite calls for fiscal responsibility, good governance, and data-informed decision making, this budget does not reflect Seattle’s values of care, prevention, equity, nor does it reflect the bold vision we need to create thriving, healthy neighborhoods for our seniors, our young people, our families and our small businesses,” Morales said.

SPD is biggest budget winner

While Seattle has a large budget of more than $8 billion due to the inclusion of the large Seattle City Light and Seattle Public Utilities portfolios, most of the council’s tinkering took place in the $1.9 billion general fund, where the city’s discretionary expenses lie.

In his proposed budget, Harrell grew the Seattle Police Department’s (SPD) budget by 16%, which included spending on the 23% raises for officers negotiated by the Seattle Police Officers Guild (SPOG), hiring bonuses, adding 19 new civilian positions for 2025, funding and growing the City’s new closed-circuit camera and real time crime software surveillance apparatus, and adding $10 million of additional overtime. Harrell also increased spending on the Unified Care Team to expand sweeps to weekends, jail contracts at both the King County Jail and the South Correctional Entity (SCORE), and his Downtown Activation Plan.

In order to do all this, in addition to transferring nearly $300 million from JumpStart and drawing down reserves, Harrell proposed many cuts to services and layoffs of City employees.

The Council largely let Harrell’s new spending stand. Indeed, when Morales suggested using some of the money proposed for SPD civilian staff to staff the real time crime center in order to reinstate some money for tenant services, Councilmember Bob Kettle appeared to lose his temper.

“This point just drives me over the edge over this continuing theme of budget actions versus committee actions. I don’t know how many budget actions should really be committee actions,” Kettle said while repeatedly pointing his finger. “And here’s the ironic thing related to this one: the committee has been doing its work.”

Centrists blockade Morales amendments

This was far from the only budget amendment proposed by Morales that was voted down. After a contentious discussion, her amendment adding $50,000 for a new tenant workgroup, which Strauss had included in his balancing package, was removed. Her amendment to add money to the Seattle Department of Human Resources to reinstate the workforce equity division, also included in the balancing package, was likewise voted down.

No other council member had any of their items removed from the balancing package by their colleagues. And neither of her statements of legislative intent (SLIs) directing Central Staff to research potential new sources of progressive revenue for the city found enough support from colleagues, in spite of being purely informational in nature.

Strauss even acknowledged this before the final budget vote, telling Morales, “I’m sorry your priorities were targeted in the amendment process.”

Transportation cuts and levy money grab

In contrast, Councilmember Rob Saka successfully defended his amendment to freeze via proviso $2 million in the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) budget in order to strongarm the agency into removing a traffic safety barrier preventing illegal left turns into the preschool his children attended along Delridge Way. Saka claimed the measure was in service to both safety and equity, without offering much detail to substantiate that assertion.

You know I had to do it to ‘em on the traffic divider Rob Saka is spending $2,000,000 to remove.

— Katherine Mitchell (@katherinemitchell.bsky.social) November 16, 2024 at 10:43 AM

[image or embed]

District 1’s first-year councilmember also successfully added an amendment to spend $1.5 million to convert a playing field where he coaches Little League from grass to turf. These two Saka amendments cost more than eight times what Morales’s rejected amendments would have cost.

Clara Cantor, a community organizer with Seattle Neighborhood Greenways, said she’s disappointed in the budget cuts to transportation improvements to comply with the American Disability Act, funding the undoing of safety projects, and diverting automated enforcement revenue away from street safety.

The new budget will also allow the council to exercise an unusual amount of control over the spending of the newly passed $1.55 billion transportation levy. Via proviso, the budget sets aside $89 million in levy dollars for 2025 subject to the council’s approval and creates a district transportation fund of $1 million for district councilmembers to spend as they see fit.

“Most concerning is the hold council has placed on a full half of the 2025 transportation levy revenue, which voters just approved by 67%,” Cantor said. “It seems to be a part of a trend towards funding pet projects instead of implementing the overwhelming will of the community.”

Council lessens layoffs, delays some cuts

The council’s budget does reverse some of Harrell’s suggested cuts, adding funding for legal services for homeless youth, a tax preparation program, services for people trying to access public assistance, and averting massive cuts at the Seattle Channel. Council amendments also reduced the number of total layoffs being faced by city employees from 76 to 48, with an additional 7 coming in 2026, while delaying other layoffs for six months.

While the newly passed budget restores some of the funding cut for tenant services and rental assistance, it doesn’t restore the City’s 2024 level of investment in these programs. It also doesn’t restore cuts to the Environmental Justice fund or indigenous-led sustainability projects. Other cuts that council went along with include parks programming and positions in the City’s IT and permitting and inspections departments.

Councilmember Cathy Moore added an amendment that will remove the right to free legal counsel for many Seattle tenants. Only those tenants making 200% or less of the federal poverty level will remain eligible, which fails to take into consideration the higher cost of living in Seattle as opposed to the country at large. A person working a full-time minimum wage job in Seattle will no longer be able to receive free legal assistance to help them protect their rights as a tenant.

“The City of Seattle has failed renters. Bad landlords already face no real accountability,” said Kate Rubin, the co-executive director of Be:Seattle. “Organizations helping renters to push back against this power imbalance and stay housed compete for scraps. The burden of rising evictions and homelessness will fall disproportionately on Black and Indigenous communities, LGBTQ+ communities, older people, and disabled people.”

Other added investments to the budget include four new 911 Emergency Communication Dispatchers that the Community Assisted Response and Engagement (CARE) department Chief Amy Barden said weren’t necessary at this time, more money for food banks and meal programs, increased investment in We Deliver Care, and funding for the creation of two new non-congregate homeless shelters. Money was also added to the storefront repair fund.

While explaining why she couldn’t vote for the budget bill, Morales teared up, saying, “To the advocates who have worked so hard to protect funding for programs that serve communities of color, that serve the most vulnerable, or that could have addressed our housing and infrastructure needs, I’m sorry that this budget will cause more harm.”

Participatory budgeting

Another chapter in the participatory budgeting saga has also drawn to a close with this budget. An unprecedented investment in participatory budgeting in Seattle was one of the main demands put forward as part of the George Floyd protests in the summer of 2020.

Then-Mayor Jenny Durkan pledged $100 million to support Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) communities, out of which $30 million was ultimately directed to participatory budgeting. During the budget process in the fall of 2020, councilmembers allocated $3 million to the Black Brilliance Project to outline how to implement a participatory budgeting process, which was meant to empower Seattle residents to have direct control over a small portion of Seattle’s budget.

People who live and work in Seattle were finally given the opportunity to vote on $27.3 million worth of projects last fall, selecting six projects to fund.

However, early in this year’s budget process, Councilmember Joy Hollingsworth expressed qualms that the selected projects didn’t directly benefit Black people. Several councilmembers mentioned their particular surprise that the expansion of CARE alternate responders was being funded by one of the projects.

Hollingsworth ultimately introduced several amendments to redirect some of the money from the voted-upon options for other uses. Around $10 million of investments were reallocated from the participatory budgeting projects in this fashion, undermining the democratic voting process laid out by the City last year.

“Oftentimes people use selective Blackness to push their agenda,” Hollingsworth said at the final budget vote. “And I’m here to say our Black community is alive and well in our city. Their voice wants to be heard. Their voice was heard on this budget.”

But in spite of several councilmembers initially questioning it, the CARE investment from participatory budgeting funds remained intact.

JumpStart raid could become permanent, imperiling affordable housing

While both Harrell and the council are touting their historic investment in affordable housing – more than $340 million in 2025 – some opponents object to this framing, given that nearly $190 million of JumpStart dollars originally intended for affordable housing are being transferred to the general fund instead. The loss of funding comes at an inopportune time. Inflation, rising construction costs, and spiking operational costs are also straining budgets at the nonprofits tasked with maintaining and expanding affordable housing.

But more long-lasting will be the deep changes to the legislation governing the JumpStart tax, which does away with the original spending plan passed in 2021 allocating the collected funds to affordable housing, small business support, equitable development, and the Green New Deal. Opponents have characterized this change as transforming the JumpStart tax into a slush fund to pay for elected officials’ pet projects.

A group of nonprofit homebuilders and community organizations opposed to this change wrote, “This new source of revenue was never meant to permanently support the city’s General Fund or address the deficit: The spending plan outlined a commitment to sustained investments in priority areas specifically because such a source could otherwise be vulnerable to the political and budgetary expediencies of subsequent administrations.”

The legislation also did away with all oversight on JumpStart dollars. Not only does Seattle’s new budget eliminate the oversight board intended to provide accountability over the large revenue source, but also the program assessment through the City Budget Office. The pro-JumpStart coalition objected to this as well.

“Mayor Harrell and the City Council made these permanent and damaging changes without thorough engagement with stakeholders or the public, reversing years of progress in a matter of weeks,” the coalition wrote in their budget letter. “This budget process demonstrates exactly why an independent oversight body is needed.”

Strauss attempted to remove a 2040 sunset clause on the JumpStart payroll tax, but Kettle introduced a successful amendment to reinstate it.

City-wide capital gains tax

In her budget remarks, Council President Sara Nelson estimated that the council’s changes to Harrell’s proposed budget increased the 2027 deficit to around $100 million, presaging more rocky budget seasons to come.

In response to this ongoing structural deficit, Moore introduced legislation that would have initiated a 2% city-wide capital gains excise tax beginning in 2026. The tax wouldn’t have applied to retirement accounts or real estate, and it would have only applied to gains above $262,000. The City estimates it will bring in anywhere between $16 million to $51 million of new progressive revenue for the City. Moore proposed that the revenue be spent on rental assistance, down payment assistance, and food assistance to help address affordability in Seattle.

The Financial and Administrative Services department estimates it will take 18 to 24 months to implement the tax. Should the tax have been passed, the City would not have received any of its revenues until April 2027.

After the council’s deep dive into the budget this year, Moore said they found there simply isn’t very much to cut, which is consistent with Morales’s observation that the council’s amendments to the budget increased city spending in 2025 by 3%.

“We need to be honest about the fact that we need more revenue to continue to provide the level of service and to meet the needs and the growing needs that the city is going to encounter, particularly with, I think, anticipated loss of federal funding,” Moore said.

The capital gains excise tax failed in committee earlier in the week, in a close 4-4 vote, with Moore, Morales, Strauss, and Hollingsworth voting in favor and Councilmember Tanya Woo abstaining. At the final budget meeting on Thursday, the bill failed by a 6-3 vote, with Woo and Hollingsworth joining the votes against.

But Moore is already looking to next year, when newly elected Councilmember Alexis Mercedes Rinck is likely to add an additional vote in favor.

“If it doesn’t pass today, okay. I’ll be back with Councilmember Morales,” Moore said. ‘I’ll be back next year.”

The Chamber’s influence on display

With the City’s budget season drawing to a close, the new council’s allegiances to downtown business interests are in full view. The Downtown Seattle Association wants to see increased investment in SPD, surveillance, jail space, and the clean-up and revitalization of downtown, all of which are heavily represented in the new budget.

Seattle’s wealthiest corporations and individuals want to see no new progressive taxes, all proposals for which were scuttled, even those simply requesting further study.

The council wasn’t even willing to remove a 2040 sunset clause on the tax they are currently depending on to fund a large proportion of the general fund, with Kettle, Moore, Nelson, Woo, Saka, and Councilmember Martiza Rivera all voting to maintain it, with Hollingsworth abstaining, as she did on all the amendments related to the JumpStart tax. (Two days later, Moore said she had changed her mind on this point.)

In a statement Thursday, Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce President and CEO Rachel Smith said she gave Harrell, Budget Chair Strauss, and the rest of the council “two thumbs up.”

“[I]t is important to close this biennial chapter with a reminder of three facts,’ Smith said. “One, today the city of Seattle has the most tax revenue it has had in the history of the city. Two, Seattle’s Office of Housing will see the most funds appropriated to the department, ever – nearly five times the amount the City spent on housing annually pre-pandemic. Three, the 2024-25 biennial budget is the largest budget in the city’s history and is a net increase from last year’s budget. Despite these facts, debates about the need for new revenue swirled – even without concrete plans to get results with additional tax revenue. Government levying taxes is a means to an end, not an act of righteousness, and it is prudent these did not move forward at this time.”

These three facts paint a misleading picture. After weathering a period of high inflation, it’s hardly a shock that City revenue and spending has gone up, even before accounting for new programs the mayor and council launched, some with Chamber support. The same financial headwinds affect affordable housing; builders need more money just to create the same amount of housing.

The crucial question for Seattle leaders to answer is whether we’re investing enough in housing, period, not simply clearing the very low bar of investing more than we did in the 2010s. Reports clearly show both an unprecedented population of unhoused people and suggest Seattle needs 112,000 new homes by 2044.

Business-aligned political action committees invested heavily in recent elections and succeeded in electing another mayor loyal to their interests and swinging the Seattle City Council to centrists. So far, those investments have paid off, stalling out a “tax the rich” push and focusing attention on budget cuts, outside of the sacred cow of SPD.

Less transparency and more austerity cuts on horizon

Beyond failing to address Seattle’s long-term revenue issues, this budget season was also marked by a noticeable decrease in transparency from previous years, with a shortened timeline, numerous last minute walk-on amendments, a key opportunity to give public comment announced only a day ahead of time, and some amendments not available for public review or media scrutiny in a timely fashion.

Nelson promised this is just the beginning, referencing the large number of SLIs in the new budget.

“What we also did was set ourselves up for making really good and detailed decisions as we look at these programs, as we receive the SLI responses during the year, and prepare ourselves for the budget and potential cuts that might make sense going forward,” Nelson said. “The criteria that we would use to decide that was looking at whether or not the outcomes of these investments are really meeting our needs and then having the political will to potentially reallocate those investments.”

Future councils will have to assess on how they’re going to address the specter of more staffing and service cuts in 2026 and beyond

Meanwhile, Seattle progressives already have one eye toward the 2025 election when they will have a chance to build on their momentum gained with Rinck’s decisive win, potentially dethroning Mayor Harrell and Council President Nelson, who are both up for reelection. The taste this budget season left in voters’ mouths may weigh heavily on who comes out on top.

Amy Sundberg is the publisher of Notes from the Emerald City, a weekly newsletter on Seattle politics and policy with a particular focus on public safety, police accountability, and the criminal legal system. She also writes science fiction, fantasy, and horror novels. She is particularly fond of Seattle’s parks, where she can often be found walking her little dog.