On Tuesday, November 19th, as the Seattle City budget process neared its end, the council rejected a city-level capital gains tax in a 4-4 vote, with outgoing Councilmember Tanya Woo abstaining. It was a remarkably close call for a council that’s been far more inclined to root around in the proverbial couch cushions searching for “efficiencies” than to hold aloft placards reading “Tax the Rich!”

If they had passed the tax, most of their constituents would have applauded. A late-breaking poll — breaking, that is, too late to sway any budget votes — from the Northwest Progressive Institute suggested that “Seattle voters want their elected representatives to levy new taxes on wealth so Jumpstart revenue can flow to housing.” A 2023 poll showed solid support for a Seattle capital gains tax, in particular.

Nonetheless, Councilmembers Sara Nelson, Rob Saka, Maritza Rivera, and Bob Kettle opposed the capital gains tax proposal, while its sponsor Cathy Moore and Councilmembers Tammy Morales, Joy Hollingsworth and Dan Strauss backed it. Mayor Bruce Harrell also opposed the proposal, but a spokesperson told the Seattle Times he is open to “a longer and more robust discussion” about progressive revenue options.

Disappointment aside, I think proponents of progressive revenue should take all this as a win, a sign of our success in shaping the public narrative. Hey, we’ve been losing a lot these days, we should pat ourselves on the back when we can.

Playing the long game on progressive taxes

Moreover, this sets us up for a real fight next year. Woo is shortly to be replaced by progressive Alexis Mercedes Rinck, following a decisive victory in the November election. That could mean a 5-4 majority for a capital gains tax — or even a supermajority, if Rob “this is the right tax at the wrong time” Saka can be convinced that the time is right.

City staff estimate that a 2% Seattle capital gains tax, layered on top of the 7% statewide tax that just survived a repeal effort with flying colors, could generate from $16 million to $51 million per year. It’s a wide range because the tax base is small (fewer than a thousand households) and revenue in a given year will depend on the vagaries of the stock market, individual decisions to sell assets, and so on.

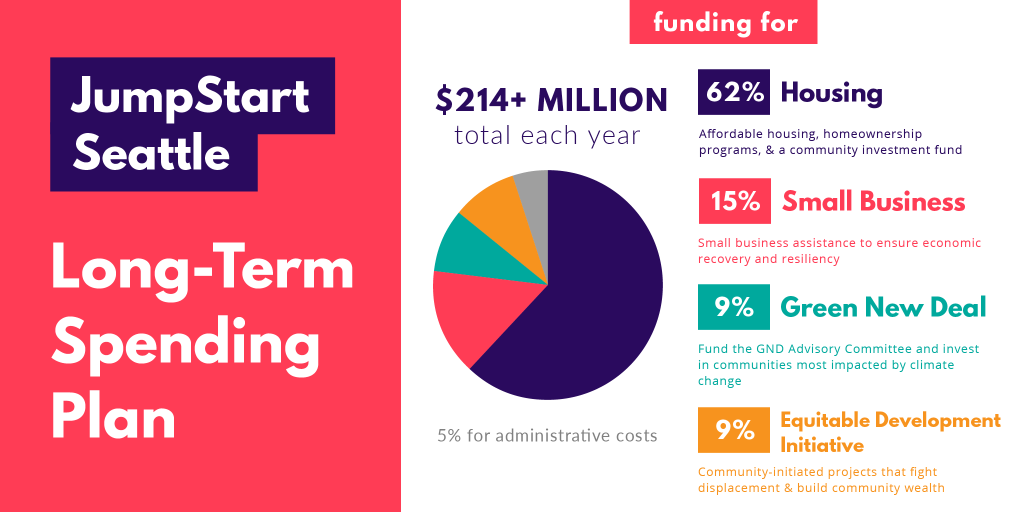

A tax that “lumpy” isn’t ideal for programs that depend on stable revenue from year to year, which could create challenges for Moore’s proposal to fund rental, down-payment, and food assistance programs. But proposing new spending at all strikes me as darkly amusing when the mayor and council just ransacked the JumpStart payroll expense tax to plug a massive structural budget hole.

If a capital gains tax does pass next year, maybe — hear me out on this one — the revenue could flow into the city’s general fund, and that would mean $16 million to $51 million more in JumpStart funds could go to affordable housing, climate investments, and equitable development projects as originally intended.

Moore’s capital gains tax proposal may not be the only option on the table. Tammy Morales has announced her interest in developing legislation for two new excise taxes, one on professional services and another on digital advertising. While her statements of legislative intent on these tax options were voted down in the budget process, nothing prevents her from continuing to develop these concepts further for introduction next year.

These two taxes are both ones the Transit Riders Union included in the Progressive Tax Options for Seattle report we released last August alongside the final report of the Seattle Revenue Stabilization Workgroup, of which I was a member. Both are relatively new ideas, and both come with some legal risks. Both can be conceived of as ways to correct loopholes or omissions in the existing tax system.

None of the revenue stabilization workgroup’s ideas made it into Mayor Harrell’s budget proposal this fall. Instead, the mayor closed a $260 million general fund deficit — and financed about $100 million in new spending on his priorities — by diverting restricted JumpStart funds and cutting City staffing and programs. An extra $200 million annually could help to generate another 2,000 affordable homes per year, according to estimates from housing providers.

Taxing professional services

Morales hopes to develop legislation to impose “a one percent excise tax on professional services, including, but not limited to, services provided by realtors, architects, accountants, and consultants.”

These are services that are currently exempted from our 10.35% state-plus-local sales tax — which, by the way, appears to be the highest of any city in the country. When Washington first introduced a retail sales tax back in 1935, it applied only to sales of tangible personal property; services simply weren’t a large part of the state’s economy. Since then, some services have been added to the tax base, including repair and rental services, construction and landscaping, and some recreation and personal services. But that still leaves many other personal and professional services untaxed.

Why these continued exemptions? There doesn’t seem to be a good reason. It doesn’t make a lot of sense that you should have to pay sales tax when hiring a plumber but not an architect. The tax compliance software company Avalara explains that professional services represent “the least taxed service area” around the country, “in large part because professional groups have powerful lobbying presences.” Only a motley handful of states — Hawaii, Kentucky, New Mexico, and South Dakota — appear to tax professional services.

Services represent a much larger portion of the economy today than they did a century ago, so governments are missing out on a lot of revenue. In 2016, the Washington State Department of Revenue estimated that repealing the sales tax exemption on personal and professional services could generate an extra $2.4 billion in state revenue and $1.1 billion in local revenue in 2019. That’s a lot!

The catch, of course, is that Seattle can’t change state law, which governs Seattle’s portion of the sales tax, too. However, the City may be able to fashion an excise tax that accomplishes something similar. TRU estimated that a tax of just 1% — the rate Morales proposed — applied to all personal and professional services that are exempt from the sales tax could generate $70 million annually. It may make sense to exclude personal services that are often provided by small low-margin businesses, such as hairdressers and nail salons. But taxing professional services, which are disproportionately used by higher-income individuals and corporations, would be very progressive, even if you imagine the entire cost being paid by the customer.

In discussions on the Revenue Stabilization Workgroup last year, city staff indicated that there could be some legal risks in structuring such an excise tax too similarly to the sales tax or to the B&O (business and occupations) tax. I’m not a lawyer, and I don’t want to get too far into the weeds here, but if a percentage-of-sales or percentage-of-revenue approach is deemed too risky, one alternative structure worth considering would be a tax-per-billable-hour. Regardless, this is an idea worth pursuing.

Taxing digital advertising

Morales’s second proposal, a tax on digital advertising, is even more intriguing. Her proposed statement of legislative intent signaled interest in “a five percent tax on digital advertising services, or ads on a digital interface, including banner advertising, search engine advertising, interstitial advertising, and other comparable advertising services.”

The reasons to pursue such a tax are legion. Digital advertising services are among the services exempted from the sales tax, as discussed above. Advertising in general is undertaxed, as it’s considered a business expense that can be deducted from federal corporate income tax. And digital advertising in particular has proved pernicious in several respects.

Google, Facebook, and other online platforms have soaked up ad revenue while spreading “borrowed” news content, contributing to the worsening funding crisis in the journalism industry. Ad-powered social media sites have proved addictive, making us miserable and depressed, with especially terrifying consequences for youth mental health. They’ve contributed to the polarization of politics and the spread of conspiracy theories. And so on.

A number of states have considered or are considering laws to tax digital advertising services, but only one has yet passed: Maryland’s Digital Advertising Gross Revenue Tax requires corporations with global annual gross revenues of at least $100 million to pay a tax on the portion of those revenues derived from digital advertising services within the state. The rate is graduated, ranging from 2.5% to 10% depending on a company’s size. Since the tax was enacted in 2021, it’s been subject to a number of lawsuits, some still unresolved. But the state is nevertheless collecting the tax, which appears to be generating on the order of $100 million annually — less than half the original projections, possibly due to noncompliance.

Seattle may not be able to copy Maryland’s tax exactly, as it would look very much like our existing B&O tax. But there are other ways one could structure a tax on digital advertising — a fraction of a penny per ad impression, for example. Another approach is to focus on the collection of data on individual consumers that’s used in targeting advertisements; House Bill 2107, introduced in the Washington state legislature in 2022, would have imposed a graduated excise tax on the collection of consumer data by commercial data collectors.

There are some sticky legal issues involved in digital ad taxes and related concepts, and additional technical challenges to implementation in a single city as opposed to statewide. But there’s also growing interest and scholarship in this area to draw upon, including an excellent recent report from UCLA entitled “Shearing the Sheep Without Skinning It: Policy Options for Extracting Revenue from Online Platforms.”

Looking ahead

I, for one, would be proud if Seattle pioneered any of these three progressive local taxes. Of course, none of it will happen without a fight. The online platforms, the purveyors of professional services, the wealthy whose incomes from capital gains exceed a quarter million dollars a year — they will oppose these proposals with energy, whereas a sales or property tax increase might warrant only a shrug.

Sitting in my inbox right now is an email from the conservative lobby group Change Washington, urging me to send a message “to make sure Seattle City Councilmembers don’t use the media’s focus on the ‘bomb cyclone’ to slyly pass a City Income Tax opposed by 68% of Seattle residents.” Yes, they’re talking about the proposed capital gains tax, the laughable implication being that the council might try to sneak it through when they take their final vote on the budget.

Those of us who want a progressive tax system, adequately funded public goods and services, and the JumpStart payroll expense tax restored to its intended uses have our work cut out for us in 2025.

Katie Wilson is General Secretary of the Transit Riders Union, a Seattle-based organization advocating for improving transit quality and making access more equitable. In 2025, she launched a run for Seattle Mayor.